The Story of Mankind: The Crusades

During three centuries there had been peace between Christians and Muslims except in Spain and in the eastern Roman Empire, the two states defending the gateways of Europe. The Muslims having conquered Syria in the seventh century were in possession of the Holy Land. But they regarded Jesus as a great prophet (though not quite as great as Mohammed), and they did not interfere with the pilgrims who wished to pray in the church which Saint Helena, the mother of the Emperor Constantine, had built on the spot of the Holy Grave. But early in the eleventh century, a Tartar tribe from the wilds of Asia, called the Seljuks or Turks, became masters of the Muslim state in western Asia and then the period of tolerance came to an end. The Turks took all of Asia Minor away from the eastern Roman Emperors and they made an end to the trade between east and west.

Alexis, the Emperor, who rarely saw anything of his Christian neighbors of the west, appealed for help and pointed to the danger which threatened Europe should the Turks take Constantinople.

The Italian cities which had established colonies along the coast of Asia Minor and Palestine, in fear for their possessions, reported terrible stories of Turkish atrocities and Christian suffering. All Europe got excited.

Pope Urban II, a Frenchman from Reims, who had been educated at the same famous cloister of Cluny which had trained Gregory VII, thought that the time had come for action. The general state of Europe was far from satisfactory. The primitive agricultural methods of that day (unchanged since Roman times) caused a constant scarcity of food. There was unemployment and hunger and these are apt to lead to discontent and riots. Western Asia in older days had fed millions. It was an excellent field for the purpose of immigration.

Therefore at the council of Clermont in France in the year 1095 the Pope arose, described the terrible horrors which the infidels had inflicted upon the Holy Land, gave a glowing description of this country which ever since the days of Moses had been overflowing with milk and honey, and exhorted the knights of France and the people of Europe in general to leave wife and child and deliver Palestine from the Turks.

A wave of religious hysteria swept across the continent. All reason stopped. Men would drop their hammer and saw, walk out of their shop and take the nearest road to the east to go and kill Turks. Children would leave their homes to “go to Palestine” and bring the terrible Turks to their knees by the mere appeal of their youthful zeal and Christian piety. Fully ninety percent of those enthusiasts never got within sight of the Holy Land. They had no money. They were forced to beg or steal to keep alive. They became a danger to the safety of the highroads and they were killed by the angry country people.

An unofficial crusade, a wild mob of honest Christians, defaulting bankrupts, penniless noblemen and fugitives from justice, following the lead of half-crazy Peter the Hermit and Walter-without-a-Cent, began their campaign against the Infidels by murdering all the Jews whom they met by the way. They got as far as Hungary and then they were all killed.

This experience taught the Church a lesson. Enthusiasm alone would not set the Holy Land free. Organization was as necessary as good-will and courage. A year was spent in training and equipping an army of 200,000 men. They were placed under command of Godfrey of Bouillon, Robert, duke of Normandy, Robert, count of Flanders, and a number of other noblemen, all experienced in the art of war.

In the year 1096 this official First Crusade started upon its long voyage. At Constantinople the knights did homage to the Emperor. (For as I have told you, traditions die hard, and a Roman Emperor, however poor and powerless, was still held in great respect). Then they crossed into Asia, killed all the Muslims who fell into their hands, stormed Jerusalem, massacred the Muslim population, and marched to the Holy Sepulcher to give praise and thanks amidst tears of piety and gratitude. But soon the Turks were strengthened by the arrival of fresh troops. Then they retook Jerusalem and in turn killed the faithful followers of the Cross.

During the next two centuries, seven other crusades took place. Gradually the Crusaders learned the technique of the trip. The land voyage was too tedious and too dangerous. They preferred to cross the Alps and go to Genoa or Venice where they took ship for the east. The Genoese and the Venetians made this trans-Mediterranean passenger service a very profitable business. They charged exorbitant rates, and when the Crusaders (most of whom had very little money) could not pay the price, these Italian “profiteers” kindly allowed them to “work their way across.” In return for a fare from Venice to Acre, the Crusader undertook to do a stated amount of fighting for the owners of their vessel. In this way Venice greatly increased her territory along the coast of the Adriatic and in Greece, where Athens became a Venetian colony, and in the islands of Cyprus and Crete and Rhodes.

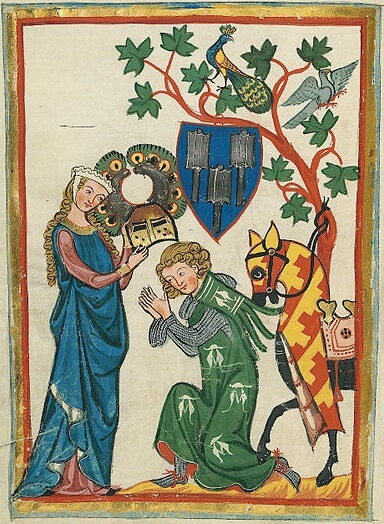

All this, however, helped little in settling the question of the Holy Land. After the first enthusiasm had worn off, a short crusading trip became part of the liberal education of every well-bred young man, and there never was any lack of candidates for service in Palestine. But the old zeal was gone. The Crusaders, who had begun their warfare with deep hatred for the Muslims and great love for the Christian people of the eastern Roman Empire and Armenia, suffered a complete change of heart. They came to despise the Greeks of Byzantium, who cheated them and frequently betrayed the cause of the Cross, and the Armenians and all the other Levantine races, and they began to appreciate the virtues of their enemies who proved to be generous and fair opponents.

Of course, it would never do to say this openly. But when the Crusader returned home, they were likely to imitate the manners which he had learned from their foe, compared to whom the average western knight was still a good deal of a country bumpkin. They also brought with them several new food-stuffs, such as peaches and spinach which he planted in their garden and grew for their own benefit. They gave up the barbarous custom of wearing a load of heavy armor and appeared in the flowing robes of silk or cotton which were the traditional habit of the followers of the Prophet and were originally worn by the Turks. Indeed the Crusades, which had begun as a punitive expedition against their religious adversaries, became a course of general instruction in civilization for millions of young Europeans.

From a military and political point of view the Crusades were a failure. Jerusalem and a number of cities were taken and lost. A dozen little kingdoms were established in Syria and Palestine and Asia Minor, but they were re-conquered by the Turks and after the year 1244 (when Jerusalem became definitely Turkish) the status of the Holy Land was the same as it had been before 1095.

But Europe had undergone a great change. The people of the west had been allowed a glimpse of the light and the sunshine and the beauty of the east. Their dreary castles no longer satisfied them. They wanted a broader life. Neither Church nor State could give this to them.

They found it in the cities.