Jackie Robinson: A Pioneer for Equality in Sports

Jack Roosevelt Robinson (January 31, 1919 – October 24, 1972) was an American pro baseball player who became the first African American to play in Major League Baseball (MLB) in the modern era. He broke the color barrier when he took the field at first base for the Brooklyn Dodgers on April 15, 1947. His signing marked the beginning of the end for racial segregation in pro baseball, which had kept black players in the Negro leagues since the 1880s.

Jackie Robinson was born in Cairo, Georgia, and grew up in Pasadena, California. A standout athlete in four sports at Pasadena Junior College and later at UCLA, he was more famous for his football skills than baseball, becoming a star for the Bruins football team. After college, he was drafted into the military during World War II but faced a court-martial for refusing to move to the back of a segregated Army bus, ultimately receiving an honorable discharge. He then joined the Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro leagues, where he caught the attention of Brooklyn Dodgers general manager Branch Rickey, who believed Robinson was the ideal choice to break Major League Baseball’s color barrier.

Family and personal life

Jack Roosevelt Robinson was born on January 31, 1919, in Cairo, Georgia, to a family of sharecroppers. The youngest of five children of Mallie (née McGriff) and Jerry Robinson, he followed siblings Edgar, Frank, Matthew (nicknamed “Mack”), and Willa Mae. His middle name was a tribute to former President Theodore Roosevelt, who had died just 25 days before his birth. In 1920, after his father left, the family moved to Pasadena, California.

The extended Robinson family settled on a residential lot with two small houses at 121 Pepper Street in Pasadena. Robinson’s mother took on various odd jobs to make ends meet. Living in relative poverty within an otherwise wealthy community, Robinson and his minority friends were often left out of local recreational activities. This led him to join a neighborhood gang, but his friend Carl Anderson convinced him to leave it behind.

John Muir High School

In 1935, Robinson finished at Washington Junior High School and moved on to John Muir Technical High School. Seeing his athletic potential, his older brothers, Frank and Mack—who was an accomplished track and field star and won silver behind Jesse Owens in the 200 meters at the 1936 Berlin Olympics—encouraged Jackie to follow his passion for sports.

At Muir Tech, Robinson was a standout athlete, competing in multiple varsity sports and earning letters in four: football, basketball, track and field, and baseball. On the baseball team, he played shortstop and catcher; in football, he was the quarterback; and in basketball, he played guard. In track and field, he excelled in the broad jump, winning awards, and he also spent time on the tennis team.

In 1936, Robinson took home the junior boys singles title at the annual Pacific Coast Negro Tennis Tournament and landed a spot on the Pomona annual baseball tournament all-star team, alongside future Hall of Famers Ted Williams and Bob Lemon. By late January 1937, the Pasadena Star-News noted that Robinson had been Muir’s standout athlete for two years, excelling in football, basketball, track, baseball, and tennis.

College career

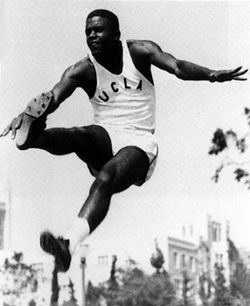

After Muir, Robinson went on to Pasadena Junior College (PJC), where he stayed active in sports, playing basketball, football, baseball, and running track. On the football team, he took on roles as both quarterback and safety. For baseball, he played shortstop, batted leadoff, and even broke an American junior college broad-jump record—previously held by his brother Mack—with a leap of 25 ft. 6½ in. on May 7, 1938. Like at Muir High, most of his teammates were white. While at PJC, he fractured his ankle during football, an injury that later delayed his military deployment. In 1938, he earned a spot on the All-Southland Junior College Team for baseball and was named the region’s Most Valuable Player.

That year, Robinson was one of 10 students named to the school’s Order of the Mast and Dagger (Omicron Mu Delta), awarded to students performing “outstanding service to the school and whose scholastic and citizenship record is worthy of recognition.” Also while at PJC, he was elected to the Lancers, a student-run police organization responsible for patrolling various school activities.

While at PJC, Robinson showed a clear impatience with authority figures he saw as racist, a trait that would appear often throughout his life. On January 25, 1938, he was arrested after openly challenging police over the detention of a black friend. He received a two-year suspended sentence, and the incident—along with other rumored clashes with police—built his reputation for standing up to racial antagonism. During his time there, a preacher named Rev. Karl Downs encouraged him to attend church regularly and became a trusted confidant. Near the end of his time at PJC, tragedy struck when his closest brother, Frank, was killed in a motorcycle accident. This loss pushed Jackie to continue his athletic career at UCLA, where he could stay close to Frank’s family.

After graduating from PJC in the spring of 1939, Robinson enrolled at UCLA, becoming the first athlete in the school’s history to earn varsity letters in four sports: baseball, basketball, football, and track.

In 1939, Robinson was one of four black players on the Bruins football team, alongside Woody Strode, Kenny Washington, and Ray Bartlett. Robinson, Washington, and Strode made up three of the four backfield spots, making UCLA the most integrated team in college football at a time when very few black students played at that level. The team went undefeated with a 6–0–4 record. Robinson wrapped up the season with an impressive 12.2 yards per carry on 42 rushes—a school record for highest rushing average in a season as of 2022—and led the NCAA in punt return average in both 1939 and 1940.

In track and field, Robinson took the 1940 NCAA long jump title with a leap of 24 ft 10¼ in (7.58 m). Baseball was his weakest sport at UCLA, where he batted just .097 in his only season, though he went 4-for-4 in his debut and stole home twice.

While a senior at UCLA, Robinson met his future wife, Rachel Isum (b.1922), a UCLA freshman who was familiar with Robinson’s athletic career at PJC. He played football as a senior, but the 1940 Bruins won only one game. In the spring, Robinson left college just shy of graduation, despite the reservations of his mother and Isum. He took a job as an assistant athletic director with the government’s National Youth Administration (NYA) in Atascadero, California.

After the government shut down NYA operations, Robinson headed to Honolulu in the fall of 1941 to play football with the semi-professional, racially integrated Honolulu Bears. Following a short season, he returned to California in December to try out as a running back for the Los Angeles Bulldogs of the Pacific Coast Football League. However, the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor soon after brought the U.S. into World War II, abruptly ending Robinson’s budding football career.

Military career

| Jackie Robinson | |

|---|---|

| Allegiance | United States |

| Branch | United States Army |

| Service years | 1942–1944 |

| Rank | Second lieutenant |

| Unit | 761st Tank Battalion |

In 1942, Robinson was drafted into the Army and assigned to a segregated cavalry unit at Fort Riley, Kansas. With the necessary qualifications, he and several other Black soldiers applied for admission to the Officer Candidate School (OCS) based at Fort Riley.

While the Army’s July 1941 guidelines for OCS were written to be race-neutral, very few Black applicants were admitted until later directives from Army leadership. Robinson and his colleagues faced months of delays with their applications. Thanks to protests from heavyweight boxing champion Joe Louis, who was stationed at Fort Riley, and support from Truman Gibson, an assistant civilian aide to the Secretary of War, they were finally accepted. This experience sparked a personal friendship between Robinson and Louis. After completing OCS, Robinson was commissioned as a second lieutenant in January 1943, and soon after, he and Isum became formally engaged.

After earning his commission, Robinson was sent to Fort Hood, Texas, where he became part of the 761st “Black Panthers” Tank Battalion. During his time there, he often spent his weekends visiting Rev. Karl Downs, the President of Sam Huston College (now Huston–Tillotson University) in nearby Austin. Back in California, Downs had been Robinson’s pastor at Scott United Methodist Church when Robinson was a student at PJC.

On July 6, 1944, an incident changed the course of Robinson’s military career. While waiting for hospital test results on the ankle he’d injured in junior college, he boarded an Army bus with a fellow officer’s wife. Even though the Army had its own unsegregated bus line, the driver told Robinson to move to the back. He refused, and the driver backed down—until the route ended, when he called the military police. Robinson was taken into custody, and later, after confronting an investigating officer about racist questioning from the officer and his assistant, the officer recommended Robinson face a court-martial.

When Robinson’s commander in the 761st, Paul L. Bates, refused to approve the legal action, Robinson was suddenly transferred to the 758th Battalion. There, the commander quickly agreed to charge him with several offenses—one being public drunkenness, even though Robinson didn’t drink. By August 1944, at the time of the court-martial, the charges had been reduced to two counts of insubordination during questioning. He was ultimately acquitted by an all-white panel of nine officers.

Although his former unit, the 761st Tank Battalion, was the first Black tank unit to see combat in World War II, Robinson’s court-martial kept him from being deployed overseas, so he never saw combat.

After being acquitted, he was sent to Camp Breckinridge, Kentucky, where he coached army athletics until his honorable discharge in November 1944. During his time there, Robinson met a former Kansas City Monarchs player from the Negro American League, who suggested he reach out to the Monarchs for a tryout. Taking the advice, Robinson wrote to the team’s co-owner, Thomas Baird.

Post-military

After his discharge, Robinson briefly rejoined his former football team, the Los Angeles Bulldogs. Soon after, he accepted an offer from his old friend and pastor, Rev. Karl Downs, to become the athletic director at Samuel Huston College in Austin, part of the Southwestern Athletic Conference. The role also included coaching the basketball team for the 1944–45 season. With the program still in its early days, few students tried out, and Robinson even stepped in to play during exhibition games. Though his teams were often outmatched, he earned respect as a tough but fair coach and caught the admiration of players like Langston University’s Marques Haynes, who would go on to join the Harlem Globetrotters.

Professional career

Negro leagues and major league prospects

In early 1945, while Robinson was attending Sam Huston College, the Kansas City Monarchs offered him a spot to play professional baseball in the Negro leagues. He signed a contract for $400 a month, roughly $7,000 today. Despite performing well on the field, Robinson found the experience frustrating. Used to the structure of college ball, he was put off by the disorganization and ties to gambling in the Negro leagues. The demanding travel schedule also strained his relationship with Isum, as they could only exchange letters. Over 47 games at shortstop for the Monarchs, he batted .387 with five home runs and 13 stolen bases, and played in the 1945 East–West All-Star Game, where he went hitless in five at-bats.

That season, Robinson explored opportunities in the major leagues. No black player had appeared in the majors since Moses Fleetwood Walker in 1884, but on April 16, the Boston Red Sox held a tryout at Fenway Park for Robinson and other black players. The event turned out to be a sham, meant mainly to appease the desegregationist views of influential Boston City Councilman Isadore H. Y. Muchnick. Even with only management in the stands, Robinson endured racial slurs. He left humiliated, and it wasn’t until July 1959—over 14 years later—that the Red Sox finally integrated their roster.

In the mid-1940s, some teams showed serious interest in signing a Black ballplayer. Branch Rickey, president and general manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers, began scouting the Negro leagues for talent and zeroed in on Jackie Robinson from a list of promising players. He interviewed Robinson for a spot with the Montreal Royals, the Dodgers’ International League farm team, wanting to be sure his choice could handle the inevitable racial abuse without reacting in anger. During their famous three-hour meeting on August 28, 1945, Robinson, surprised by the question, asked if Rickey wanted someone afraid to fight back. Rickey clarified he needed someone “with guts enough not to fight back.” Once Robinson promised to “turn the other cheek” to racial hostility, Rickey signed him for $600 a month (about $10,500 today), without compensating the Monarchs, believing Negro league players were free agents. Rickey also consulted Wendell Smith of the Pittsburgh Courier, who, according to Indians owner Bill Veeck, played a key role in convincing him to choose Robinson, though he never received full credit.

Rickey asked Robinson to keep their deal under wraps for a while, but promised to officially sign him before November 1, 1945. On October 23, it was announced that Robinson would join the Royals for the 1946 season, and that same day, with Royals and Dodgers representatives watching, he signed his contract. Known later as “The Noble Experiment,” Robinson became the first Black player in the International League since the 1880s. He wasn’t necessarily the top player in the Negro leagues, which upset stars like Satchel Paige and Josh Gibson. Larry Doby, who integrated the American League the same year, said many Black players were disappointed because they felt Josh Gibson was the best. Doby believed Gibson’s early death was partly due to heartbreak.

Rickey’s offer gave Robinson the chance to leave the Monarchs and their exhausting bus rides, so he returned home to Pasadena. That September, he joined Chet Brewer’s Kansas City Royals, a post-season barnstorming team in the California Winter League. Later that off-season, he took a brief tour of South America with another barnstorming team, while his fiancée Isum explored nursing opportunities in New York City. On February 10, 1946, Robinson and Isum were married by their longtime friend, Rev. Karl Downs.

Post-baseball life

Robinson once told future Hall of Famer Hank Aaron, “Baseball is great, but the greatest thing is what you do after your career is over.” He retired at 37 on January 5, 1957, and later that year, after struggling with various health issues, was diagnosed with diabetes, a condition that also affected his brothers. Though he began insulin treatments, medical advances at the time couldn’t stop the disease from gradually taking a toll on his health.

In October 1959, Robinson walked into the whites-only waiting room at Greenville Municipal Airport. When airport police told him to leave, he refused. Later, during a NAACP speech in Greenville, South Carolina, he called for “complete freedom” and encouraged Black citizens to vote and stand up against their second-class status. By the following January, about 1,000 people marched to the airport on New Year’s Day, leading to its desegregation soon after.

In his first year of eligibility for the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1962, Robinson encouraged voters to consider only his on-field qualifications, rather than his cultural impact on the game. He was elected on the first ballot, becoming the first Black American player inducted into the Cooperstown museum.

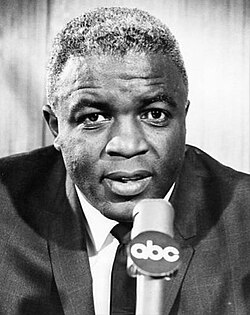

In 1965, Robinson became the first Black American analyst for ABC’s Major League Baseball Game of the Week. The following year, he took on the role of general manager for the short-lived Brooklyn Dodgers of the Continental Football League. By 1972, he was working as a part-time commentator for Montreal Expos telecasts.

From 1957 to 1964, Robinson served as vice president for personnel at Chock full o’Nuts, becoming the first Black American to hold such a position at a major U.S. corporation. He saw his business career as a way to advance opportunities for Black people in commerce and industry. In 1957, he chaired the NAACP’s million-dollar Freedom Fund Drive and remained on the organization’s board until 1967. In 1964, alongside Harlem businessman Dunbar McLaurin, he co-founded Freedom National Bank, a Black-owned and operated commercial bank in Harlem, serving as its first board chairman. In 1970, he started the Jackie Robinson Construction Company to build housing for low-income families.

Robinson stayed active in politics after his baseball career, calling himself a political independent while holding some conservative views, such as support for the Vietnam War—he even wrote to Martin Luther King Jr. defending the Johnson Administration’s policy. He backed Richard Nixon in the 1960 race against John F. Kennedy, but later praised Kennedy’s civil rights stance. Robinson strongly opposed Barry Goldwater’s 1964 presidential bid due to Goldwater’s resistance to the Civil Rights Act, and worked as one of six national directors for Nelson Rockefeller’s unsuccessful Republican nomination campaign. When Goldwater won the nomination, Robinson left the convention, saying he now better understood “how it must have felt to be a Jew in Hitler’s Germany.” He later served as special assistant for community affairs after Rockefeller was re-elected governor of New York in 1966, and in 1971 was appointed to the New York State Athletic Commission. By 1968, Robinson had broken with the Republican Party and supported Hubert Humphrey over Nixon in the presidential election.

Robinson spoke out against the major leagues’ continued lack of minority managers and front-office staff, even turning down an invitation to an old-timers’ game at Yankee Stadium in 1969. His final public appearance came on October 15, 1972, just nine days before his death, when he threw the ceremonial first pitch before Game 2 of the World Series at Riverfront Stadium in Cincinnati. While accepting a plaque celebrating the twenty-fifth anniversary of his MLB debut, he remarked, “I’ll be much more pleased and proud when I can look down that third base coaching line and see a Black face managing in baseball.” That dream wasn’t realized until after his death, when the Cleveland Indians hired Frank Robinson (no relation), a future Hall of Famer, as manager following the 1974 season. Despite the achievements of both Robinsons and other Black players, the number of Black American players in Major League Baseball has declined since the 1970s.

Family life and death

After Jackie Robinson retired from baseball, his wife Rachel Robinson built a career in academic nursing. She worked as an assistant professor at the Yale School of Nursing and served as director of nursing at the Connecticut Mental Health Center. Rachel was also on the board of the Freedom National Bank until it closed in 1990. Together, she and Jackie had three children: Jackie Robinson Jr. (1946–1971), Sharon Robinson (born 1950), and David Robinson (born 1952).

Jackie Robinson’s eldest son, Jackie Robinson Jr., faced emotional challenges early in life and attended special education. Seeking structure, he joined the Army, served in the Vietnam War, and was wounded in action on November 19, 1965. After leaving the service, he battled drug addiction but successfully completed treatment at Daytop Village in Seymour, Connecticut, later becoming a counselor there. Tragically, on June 17, 1971, at just 24 years old, he died in a car accident. His struggles with addiction deeply impacted Robinson Sr., inspiring him to become a passionate anti-drug advocate in his later years.

Robinson didn’t live much longer than his son. In 1968, he had a heart attack, and ongoing issues from heart disease and diabetes left him nearly blind by middle age. On October 24, 1972, he died of a heart attack at his home on Cascade Road in North Stamford, Connecticut, at the age of 53. His funeral, held three days later at Riverside Church in Upper Manhattan, drew 2,500 mourners, including many former teammates, baseball legends, and basketball star Bill Russell as pallbearers, with the eulogy delivered by Rev. Jesse Jackson. Tens of thousands lined the route to Cypress Hills Cemetery in Brooklyn, where he was laid to rest beside his son Jackie and mother-in-law Zellee Isum. Twenty-five years later, the Interboro Parkway, which runs near his gravesite, was renamed the Jackie Robinson Parkway in his honor.

After Robinson’s passing, his widow founded the Jackie Robinson Foundation and, at 103 years old, still serves as an officer in 2025. On April 15, 2008, she announced plans for the foundation to open a museum dedicated to Jackie in Lower Manhattan in 2010. Robinson’s daughter, Sharon, went on to become a midwife, educator, director of educational programming for MLB, and author of two books about her father. His youngest son, David, a father of ten, is a coffee grower and social activist in Tanzania.