Tim’s Football

Peter,” called Tim, “come out here.”

Tim was in Peter’s front yard. He was kicking something about.

“What are you doing?” asked Peter.

“I am playing football. Don’t you know that all the big boys play football in the autumn? My mother made me this football. It is a good one. See!”

Tim picked up his ball. He handed it to Peter. It was just a bag made of cloth. It was stuffed with rags.

“Yes, it is a good one,” said Peter. “One day I made a football out of burdock burrs. But it came to pieces, when I kicked it. Yours will not do that.”

“No,” said Tim, “it will not. My mother said that I may kick it to pieces, if I can. Then my father will bring me a real one from Large Village.”

“Let me take it a minute, Tim. Let me show it to my mother. She will make one for me.”

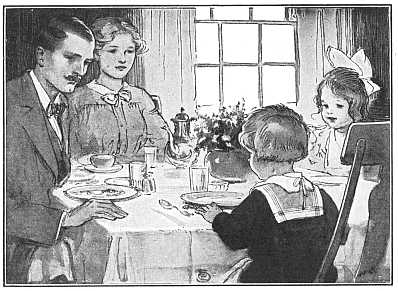

Mrs. Howe made Peter a football. It was just like Tim’s. It did not take her very long to do it. She made a strong bag on the sewing machine. She stuffed it with rags. Then she sewed up the end.

“There,” she said, “now you both have footballs. I think that they are very good ones. You may go to Tim’s and play with them. Tim has some leaves up at his house for you to jump in.”

Tim and Peter kicked their footballs all the way up the hill. Sometimes the balls did not go straight. Sometimes, when they tried, the boys did not kick them at all.

Once Peter kicked very hard. He did not touch his ball. He kicked so hard that he fell down.

“See all your leaves, Tim,” said Peter. “Your yard is fall of them. Let’s rake them up. Maybe we can have a bonfire.”

“We can rake them,” said Tim. “But we cannot burn them. I heard my father say that he should keep our leaves.”

“What for?” asked Peter.

“He is going to put them in a big pile,” said Tim. “He is going to cover them over.

“After he has left them in a pile for a long, long time, they will rot. Then they will be good for the garden.”

“I should rather have a bonfire,” said Peter.

“So should I,” said Tim. “But my father would not. He gets things to sell from his garden. So he has to make them grow fast.”

“My father does not,” said Peter. “He keeps a store. He has the post office, too. That is in his store. I have seen him put the letters into boxes.”

“So have I,” said Tim. “And I have had a letter, too. Let’s rake up a pile of leaves now. We can jump in them.”

“Where is my football?” asked Peter.

“I do not know, Peter. It must be somewhere in the leaves. We can find it when we rake them up. Oh, see mine!”

“There is a hole in it,” said Peter. “The insides are sticking out. Now you can have a real one, Tim. Your mother said so. Let us take it in to show her.”

When the boys came out of the house, Tim said, “Polly and I buried you in the sand the other day. Now you bury me in the leaves.”

He lay down and Peter piled leaves all over him. He even covered up his face. The leaves were very light. Tim liked the smell of them.

Soon he jumped up. He did not need anyone to dig him out. Then he covered Peter all over.

“Do not go to sleep,” he said. “If you do, we shall never get the leaves raked up. Now you have been buried long enough. Come out!”

Next, they tried to bury Collie and Wag-wag. But the dogs would not lie still. They thought that it was some kind of game. They wished to play, too.

At last the boys found Peter’s football.

“I must take this home, before I lose it again,” said Peter. “Goodbye, Tim. I have had a good time. Come and play with me this afternoon.”