Archive for the ‘Rebecca Of Sunnybrook Farm’ Category

Just before Thanksgiving the affairs of the Simpsons reached what might have been called a crisis, even in their family, which had been born and reared in a state of adventurous poverty and perilous uncertainty.

Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm Chapter 12: See The Pale Martyr

It was about this time that Rebecca, who had been reading about the Spartan boy, conceived the idea of some mild form of self-punishment to be applied on occasions when she was fully convinced in her own mind that it would be salutary. The immediate cause of the decision was a somewhat sadder accident than was common, even in a career prolific in such things.

Clad in her best, Rebecca had gone to take tea with the Cobbs; but while crossing the bridge she was suddenly overcome by the beauty of the river and leaned over the newly painted rail to feast her eyes on the dashing torrent of the fall. Resting her elbows on the topmost board, and inclining her little figure forward in delicious ease, she stood there dreaming.

The river above the dam was a glassy lake with all the loveliness of blue heaven and green shore reflected in its surface; the fall was a swirling wonder of water, ever pouring itself over and over inexhaustibly in luminous golden gushes that lost themselves in snowy depths of foam. Sparkling in the sunshine, gleaming under the summer moon, cold and gray beneath a November sky, trickling over the dam in some burning July drought, swollen with turbulent power in some April freshet, how many young eyes gazed into the mystery and majesty of the falls along that river, and how many young hearts dreamed out their futures leaning over the bridge rail, seeing “the vision splendid” reflected there and often, too, watching it fade into “the light of common day.”

Rebecca never went across the bridge without bending over the rail to wonder and to ponder, and at this special moment she was putting the finishing touches on a poem.

Two maidens by a river strayed

Down in the state of Maine.

The one was called Rebecca,

The other Emma Jane.

“I would my life were like the stream,”

Said her named Emma Jane,

“So quiet and so very smooth,

So free from every pain.”

“I’d rather be a little drop

In the great rushing fall!

I would not choose the glassy lake,

‘T would not suit me at all!”

(It was the darker maiden spoke

The words I just have stated,

The maidens twain were simply friends

And not at all related.)

But O! alas I we may not have

The things we hope to gain;

The quiet life may come to me,

The rush to Emma Jane!

“I don’t like ‘the rush to Emma Jane,’ and I can’t think of anything else. Oh! what a smell of paint! Oh! it is ON me! Oh! it’s all over my best dress! Oh I what will aunt Miranda say!”

With tears of self-reproach streaming from her eyes, Rebecca flew up the hill, sure of sympathy, and hoping against hope for help of some sort.

Mrs. Cobb took in the situation at a glance, and professed herself able to remove almost any stain from almost any fabric; and in this she was corroborated by uncle Jerry, who vowed that mother could git anything out. Sometimes she took the cloth right along with the spot, but she had a sure hand, mother had!

The damaged garment was removed and partially immersed in turpentine, while Rebecca graced the festal board clad in a blue calico wrapper of Mrs. Cobb’s.

“Don’t let it take your appetite away,” crooned Mrs. Cobb. “I’ve got cream biscuit and honey for you. If the turpentine don’t work, I’ll try French chalk, magneshy, and warm suds. If they fail, father shall run over to Strout’s and borrow some of the stuff Marthy got in Milltown to take the currant pie out of her weddin’ dress.”

“I ain’t got to understandin’ this paintin’ accident yet,” said uncle Jerry jocosely, as he handed Rebecca the honey. “Bein’ as how there’s ‘Fresh Paint’ signs hung all over the breedge, so ‘t a blind asylum couldn’t miss ’em, I can’t hardly account for your gettin’ int’ the pesky stuff.”

“I didn’t notice the signs,” Rebecca said dolefully. “I suppose I was looking at the falls.”

“The falls has been there sence the beginnin’ o’ time, an’ I cal’late they’ll be there till the end on ‘t; so you needn’t ‘a’ been in sech a brash to git a sight of ’em. Children comes turrible high, mother, but I s’pose we must have ’em!” he said, winking at Mrs. Cobb.

When supper was cleared away Rebecca insisted on washing and wiping the dishes, while Mrs. Cobb worked on the dress with an energy that plainly showed the gravity of the task. Rebecca kept leaving her post at the sink to bend anxiously over the basin and watch her progress, while uncle Jerry offered advice from time to time.

“You must ‘a’ laid all over the breedge, deary,” said Mrs. Cobb; “for the paint ‘s not only on your elbows and yoke and waist, but it about covers your front breadth.”

As the garment began to look a little better Rebecca’s spirits took an upward turn, and at length she left it to dry in the fresh air, and went into the sitting room.

“Have you a piece of paper, please?” asked Rebecca. “I’ll copy out the poetry I was making while I was lying in the paint.”

Mrs. Cobb sat by her mending basket, and uncle Jerry took down a gingham bag of strings and occupied himself in taking the snarls out of them,—a favorite evening amusement with him.

Rebecca soon had the lines copied in her round school-girl hand, making such improvements as occurred to her on sober second thought.

THE TWO WISHES BY REBECCA RANDALL

Two maidens by a river strayed,

‘T was in the state of Maine.

Rebecca was the darker one,

The fairer, Emma Jane.

The fairer maiden said, “I would

My life were as the stream;

So peaceful, and so smooth and still,

So pleasant and serene.”

“I’d rather be a little drop

In the great rushing fall;

I’d never choose the quiet lake;

‘T would not please me at all.”

(It was the darker maiden spoke

The words we just have stated;

The maidens twain were simply friends,

Not sisters, or related.)

But O! alas! we may not have

The things we hope to gain.

The quiet life may come to me,

The rush to Emma Jane!

She read it aloud, and the Cobbs thought it not only surpassingly beautiful, but a marvelous production.

“I guess if that writer that lived on Congress Street in Portland could ‘a’ heard your poetry he’d ‘a’ been astonished,” said Mrs. Cobb. “If you ask me, I say this piece is as good as that one o’ his, ‘Tell me not in mournful numbers;’ and consid’able clearer.”

“I never could fairly make out what ‘mournful numbers’ was,” remarked Mr. Cobb critically.

“Then I guess you never studied fractions!” flashed Rebecca. “See here, uncle Jerry and aunt Sarah, would you write another verse, especially for a last one, as they usually do—one with ‘thoughts’ in it—to make a better ending?”

“If you can grind ’em out jest by turnin’ the crank, why I should say the more the merrier; but I don’t hardly see how you could have a better endin’,” observed Mr. Cobb.

“It is horrid!” grumbled Rebecca. “I ought not to have put that ‘me’ in. I’m writing the poetry. Nobody ought to know it is me standing by the river; it ought to be ‘Rebecca,’ or ‘the darker maiden;’ and ‘the rush to Emma Jane’ is simply dreadful. Sometimes I think I never will try poetry, it’s so hard to make it come right; and other times it just says itself. I wonder if this would be better?

But O! alas! we may not gain

The good for which we pray

The quiet life may come to one

Who likes it rather gay,

I don’t know whether that is worse or not. Now for a new last verse!”

In a few minutes the poetess looked up, flushed and triumphant. “It was as easy as nothing. Just hear!” And she read slowly, with her pretty, pathetic voice:

Then if our lot be bright or sad,

Be full of smiles, or tears,

The thought that God has planned it so

Should help us bear the years.

Mr. and Mrs. Cobb exchanged dumb glances of admiration; indeed uncle Jerry was obliged to turn his face to the window and wipe his eyes furtively with the string-bag.

“How in the world did you do it?” Mrs. Cobb exclaimed.

“Oh, it’s easy,” answered Rebecca; “the hymns at meeting are all like that. You see there’s a school newspaper printed at Wareham Academy once a month. Dick Carter says the editor is always a boy, of course; but he allows girls to try and write for it, and then chooses the best. Dick thinks I can be in it.”

“In it!” exclaimed uncle Jerry. “I shouldn’t be a bit surprised if you had to write the whole paper; an’ as for any boy editor, you could lick him writin’, I bet ye, with one hand tied behind ye.”

“Can we have a copy of the poetry to keep in the family Bible?” inquired Mrs. Cobb respectfully.

“Oh! would you like it?” asked Rebecca. “Yes indeed! I’ll do a clean, nice one with violet ink and a fine pen. But I must go and look at my poor dress.”

The old couple followed Rebecca into the kitchen. The frock was quite dry, and in truth it had been helped a little by aunt Sarah’s ministrations; but the colors had run in the rubbing, the pattern was blurred, and there were muddy streaks here and there. As a last resort, it was carefully smoothed with a warm iron, and Rebecca was urged to attire herself, that they might see if the spots showed as much when it was on.

They did, most uncompromisingly, and to the dullest eye. Rebecca gave one searching look, and then said, as she took her hat from a nail in the entry, “I think I’ll be going. Goodnight! If I’ve got to have a scolding, I want it quick, and get it over.”

“Poor little onlucky misfortunate thing!” sighed uncle Jerry, as his eyes followed her down the hill. “I wish she could pay some attention to the ground under her feet; but I vow, if she was ourn I’d let her slop paint all over the house before I could scold her. Here’s her poetry she’s left behind. Read it out ag’in, mother. Land!” he continued, chuckling, as he lighted his cob pipe; “I can just see the last flap o’ that boy-editor’s shirt tail as he legs it for the woods, while Rebecky settles down in his revolvin’ cheer! I’m puzzled as to what kind of a job editin’ is, exactly; but she’ll find out, Rebecky will. An’ she’ll just edit for all she’s worth!

“‘The thought that God has planned it so

Should help us bear the years.’

Land, mother! that takes right holt, kind o’ like the gospel. How do you suppose she thought that out?”

“She couldn’t have thought it out at her age,” said Mrs. Cobb; “she must have just guessed it was that way. We know some things without bein’ told, Jeremiah.”

Rebecca took her scolding (which she richly deserved) like a soldier. There was considerable of it, and Miss Miranda remarked, among other things, that so absentminded a child was sure to grow up into a driveling idiot. She was bidden to stay away from Alice Robinson’s birthday party, and doomed to wear her dress, stained and streaked as it was, until it was worn out. Aunt Jane six months later mitigated this martyrdom by making her a ruffled dimity pinafore, artfully shaped to conceal all the spots. She was blessedly ready with these mediations between the poor little sinner and the full consequences of her sin.

When Rebecca had heard her sentence and gone to the north chamber she began to think. If there was anything she did not wish to grow into, it was an idiot of any sort, particularly a driveling one; and she resolved to punish herself every time she incurred what she considered to be the righteous displeasure of her virtuous relative. She didn’t mind staying away from Alice Robinson’s. She had told Emma Jane it would be like a picnic in a graveyard, the Robinson house being as near an approach to a tomb as a house can manage to be. Children were commonly brought in at the back door, and requested to stand on newspapers while making their call, so that Alice was begged by her friends to “receive” in the shed or barn whenever possible. Mrs. Robinson was not only “turrible neat,” but “turrible close,” so that the refreshments were likely to be peppermint lozenges and glasses of well water.

After considering the relative values, as penances, of a piece of haircloth worn next the skin, and a pebble in the shoe, she dismissed them both. The haircloth could not be found, and the pebble would attract the notice of the Argus-eyed aunt, besides being a foolish bar to the activity of a person who had to do housework and walk a mile and a half to school.

The Martyr Sacrifices Her Parasol

The Martyr Sacrifices Her Parasol

Her first experimental attempt at martyrdom had not been a distinguished success. She had stayed at home from the Sunday school concert, a function of which, in ignorance of more alluring ones, she was extremely fond. As a result of her desertion, two infants who relied upon her to prompt them (she knew the verses of all the children better than they did themselves) broke down ignominiously. The class to which she belonged had to read a difficult chapter of Scripture in rotation, and the various members spent an arduous Sabbath afternoon counting out verses according to their seats in the pew, and practicing the ones that would inevitably fall to them. They were too ignorant to realize, when they were called upon, that Rebecca’s absence would make everything come wrong, and the blow descended with crushing force when the Jebusites and Amorites, the Girgashites, Hivites, and Perizzites had to be pronounced by the persons of all others least capable of grappling with them.

Self-punishment, then, to be adequate and proper, must begin, like charity, at home, and unlike charity should end there too. Rebecca looked about the room vaguely as she sat by the window. She must give up something, and truth to tell she possessed little to give, hardly anything but—yes, that would do, the beloved pink parasol. She could not hide it in the attic, for in some moment of weakness she would be sure to take it out again. She feared she had not the moral energy to break it into bits. Her eyes moved from the parasol to the apple trees in the side yard, and then fell to the well curb. That would do; she would fling her dearest possession into the depths of the water. Action followed quickly upon decision, as usual. She slipped down in the darkness, stole out the front door, approached the place of sacrifice, lifted the cover of the well, gave one unresigned shudder, and flung the parasol downward with all her force. At the crucial instant of renunciation she was greatly helped by the reflection that she closely resembled the heathen mothers who cast their babes to the crocodiles in the Ganges.

She slept well and arose refreshed, as a consecrated spirit always should and sometimes does. But there was great difficulty in drawing water after breakfast. Rebecca, chastened and uplifted, had gone to school. Abijah Flagg was summoned, lifted the well cover, explored, found the inciting cause of trouble, and with the help of Yankee wit succeeded in removing it. The fact was that the ivory hook of the parasol had caught in the chain gear, and when the first attempt at drawing water was made, the little offering of a contrite heart was jerked up, bent, its strong ribs jammed into the well side, and entangled with a twig root. It is needless to say that no sleight-of-hand performer, however expert, unless aided by the powers of darkness, could have accomplished this feat; but a luckless child in the pursuit of virtue had done it with a turn of the wrist.

We will draw a veil over the scene that occurred after Rebecca’s return from school. You who read may be well advanced in years, you may be gifted in rhetoric, ingenious in argument; but even you might quail at the thought of explaining the tortuous mental processes that led you into throwing your beloved pink parasol into Miranda Sawyer’s well. Perhaps you feel equal to discussing the efficacy of spiritual self-chastisement with a person who closes her lips into a thin line and looks at you out of blank, uncomprehending eyes! Common sense, right, and logic were all arrayed on Miranda’s side. When poor Rebecca, driven to the wall, had to avow the reasons lying behind the sacrifice of the sunshade, her aunt said, “Now see here, Rebecca, you’re too big to be whipped, and I shall never whip you; but when you think you ain’t punished enough, just tell me, and I’ll make out to invent a little something more. I ain’t so smart as some folks, but I can do that much; and whatever it is, it’ll be something that won’t punish the whole family, and make ’em drink ivory dust, wood chips, and pink silk rags with their water.”

Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm Chapter 11: The Stirring Of The Powers

Rebecca’s visit to Milltown was all that her glowing fancy had painted it, except that recent readings about Rome and Venice disposed her to believe that those cities might have an advantage over Milltown in the matter of mere pictorial beauty. So soon does the soul outgrow its mansions that after once seeing Milltown her fancy ran out to the future sight of Portland; for that, having islands and a harbor and two public monuments, must be far more beautiful than Milltown, which would, she felt, take its proud place among the cities of the earth, by reason of its tremendous business activity rather than by any irresistible appeal to the imagination.

It would be impossible for two children to see more, do more, walk more, talk more, eat more, or ask more questions than Rebecca and Emma Jane did on that eventful Wednesday.

“She’s the best company I ever see in all my life,” said Mrs. Cobb to her husband that evening. “We ain’t had a dull minute this day. She’s well-mannered, too; she didn’t ask for anything, and was thankful for whatever she got. Did you watch her face when we went into that tent where they was actin’ out Uncle Tom’s Cabin? And did you take notice of the way she told us about the book when we sat down to have our ice cream? I tell you Harriet Beecher Stowe herself couldn’t ‘a’ done it better justice.”

“I took it all in,” responded Mr. Cobb, who was pleased that “mother” agreed with him about Rebecca. “I ain’t sure but she’s goin’ to turn out somethin’ remarkable,—a singer, or a writer, or a lady doctor like that Miss Parks up to Cornish.”

“Lady doctors are always home’paths, ain’t they?” asked Mrs. Cobb, who, it is needless to say, was distinctly of the old school in medicine.

“Land, no, mother; there ain’t no home’path ’bout Miss Parks—she drives all over the country.”

“I can’t see Rebecca as a lady doctor, somehow,” mused Mrs. Cobb. “Her gift o’ gab is what’s goin’ to be the makin’ of her; mebbe she’ll lecture, or recite pieces, like that Portland elocutionist that come out here to the harvest supper.”

“I guess she’ll be able to write down her own pieces,” said Mr. Cobb confidently; “she could make ’em up faster ‘n she could read ’em out of a book.”

“It’s a pity she’s so plain looking,” remarked Mrs. Cobb, blowing out the candle.

“Plain looking, mother?” exclaimed her husband in astonishment. “Look at the eyes of her; look at the hair of her, an’ the smile, an’ that there dimple! Look at Alice Robinson, that’s called the prettiest child on the river, an’ see how Rebecca shines her ri’ down out o’ sight! I hope Mirandy’ll favor her comin’ over to see us real often, for she’ll let off some of her steam here, an’ the brick house’ll be consid’able safer for everybody concerned. We’ve known what it was to have children, even if ‘t was more ‘n thirty years ago, an’ we can make allowances.”

Notwithstanding the encomiums of Mr. and Mrs. Cobb, Rebecca made a poor hand at composition writing at this time. Miss Dearborn gave her every sort of subject that she had ever been given herself: Cloud Pictures; Abraham Lincoln; Nature; Philanthropy; Slavery; Intemperance; Joy and Duty; Solitude; but with none of them did Rebecca seem to grapple satisfactorily.

“Write as you talk, Rebecca,” insisted poor Miss Dearborn, who secretly knew that she could never manage a good composition herself.

“But gracious me, Miss Dearborn! I don’t talk about nature and slavery. I can’t write unless I have something to say, can I?”

“That is what compositions are for,” returned Miss Dearborn doubtfully; “to make you have things to say. Now in your last one, on solitude, you haven’t said anything very interesting, and you’ve made it too common and everyday to sound well. There are too many ‘yous’ and ‘yours’ in it; you ought to say ‘one’ now and then, to make it seem more like good writing. ‘One opens a favorite book;’ ‘One’s thoughts are a great comfort in solitude,’ and so on.”

“I don’t know any more about solitude this week than I did about joy and duty last week,” grumbled Rebecca.

“You tried to be funny about joy and duty,” said Miss Dearborn reprovingly; “so of course you didn’t succeed.”

“I didn’t know you were going to make us read the things out loud,” said Rebecca with an embarrassed smile of recollection.

“Joy and Duty” had been the inspiring subject given to the older children for a theme to be written in five minutes.

Rebecca had wrestled, struggled, perspired in vain. When her turn came to read she was obliged to confess she had written nothing.

“You have at least two lines, Rebecca,” insisted the teacher, “for I see them on your slate.”

“I’d rather not read them, please; they are not good,” pleaded Rebecca.

“Read what you have, good or bad, little or much; I am excusing nobody.”

Rebecca rose, overcome with secret laughter dread, and mortification; then in a low voice she read the couplet:

When Joy and Duty clash

Let Duty go to smash.

Dick Carter’s head disappeared under the desk, while Living Perkins choked with laughter.

Miss Dearborn laughed too; she was little more than a girl, and the training of the young idea seldom appealed to the sense of humor.

“You must stay after school and try again, Rebecca,” she said, but she said it smilingly. “Your poetry hasn’t a very nice idea in it for a good little girl who ought to love duty.”

“It wasn’t MY idea,” said Rebecca apologetically. “I had only made the first line when I saw you were going to ring the bell and say the time was up. I had ‘clash’ written, and I couldn’t think of anything then but ‘hash’ or ‘rash’ or ‘smash.’ I’ll change it to this:

When Joy and Duty clash,

‘T is Joy must go to smash.”

“That is better,” Miss Dearborn answered, “though I cannot think ‘going to smash’ is a pretty expression for poetry.”

Having been instructed in the use of the indefinite pronoun “one” as giving a refined and elegant touch to literary efforts, Rebecca painstakingly rewrote her composition on solitude, giving it all the benefit of Miss Dearborn’s suggestion. It then appeared in the following form, which hardly satisfied either teacher or pupil:

SOLITUDE

It would be false to say that one could ever be alone when one has one’s lovely thoughts to comfort one. One sits by one’s self, it is true, but one thinks; one opens one’s favorite book and reads one’s favorite story; one speaks to one’s aunt or one’s brother, fondles one’s cat, or looks at one’s photograph album. There is one’s work also: what a joy it is to one, if one happens to like work. All one’s little household tasks keep one from being lonely. Does one ever feel bereft when one picks up one’s chips to light one’s fire for one’s evening meal? Or when one washes one’s milk pail before milking one’s cow? One would fancy not.

R. R. R.

“It is perfectly dreadful,” sighed Rebecca when she read it aloud after school. “Putting in ‘one’ all the time doesn’t make it sound any more like a book, and it looks silly besides.”

“You say such queer things,” objected Miss Dearborn. “I don’t see what makes you do it. Why did you put in anything so common as picking up chips?”

“Because I was talking about ‘household tasks’ in the sentence before, and it IS one of my household tasks. Don’t you think calling supper ‘one’s evening meal’ is pretty? and isn’t ‘bereft’ a nice word?”

“Yes, that part of it does very well. It is the cat, the chips, and the milk pail that I don’t like.”

“All right!” sighed Rebecca. “Out they go; Does the cow go too?”

“Yes, I don’t like a cow in a composition,” said the difficult Miss Dearborn.

The Milltown trip had not been without its tragic consequences of a small sort; for the next week Minnie Smellie’s mother told Miranda Sawyer that she’d better look after Rebecca, for she was given to “swearing and profane language;” that she had been heard saying something dreadful that very afternoon, saying it before Emma Jane and Living Perkins, who only laughed and got down on all fours and chased her.

Rebecca, on being confronted and charged with the crime, denied it indignantly, and aunt Jane believed her.

“Search your memory, Rebecca, and try to think what Minnie overheard you say,” she pleaded. “Don’t be ugly and obstinate, but think real hard. When did they chase you up the road, and what were you doing?”

A sudden light broke upon Rebecca’s darkness.

“Oh! I see it now,” she exclaimed. “It had rained hard all the morning, you know, and the road was full of puddles. Emma Jane, Living, and I were walking along, and I was ahead. I saw the water streaming over the road towards the ditch, and it reminded me of Uncle Tom’s Cabin at Milltown, when Eliza took her baby and ran across the Mississippi on the ice blocks, pursued by the bloodhounds. We couldn’t keep from laughing after we came out of the tent because they were acting on such a small platform that Eliza had to run round and round, and part of the time the one dog they had pursued her, and part of the time she had to pursue the dog. I knew Living would remember, too, so I took off my waterproof and wrapped it round my books for a baby; then I shouted, ‘My God! The river!’ just like that—the same as Eliza did in the play; then I leaped from puddle to puddle, and Living and Emma Jane pursued me like the bloodhounds. It’s just like that stupid Minnie Smellie who doesn’t know a game when she sees one. And Eliza wasn’t swearing when she said ‘My God! the river!’ It was more like praying.”

“Well, you’ve got no call to be prayin’, anymore than swearin’, in the middle of the road,” said Miranda; “but I’m thankful it’s no worse. You’re born to trouble as the sparks fly upward, an’ I’m afraid you always will be till you learn to bridle your unruly tongue.”

“I wish sometimes that I could bridle Minnie’s,” murmured Rebecca, as she went to set the table for supper.

“I declare she is the beatin’est child!” said Miranda, taking off her spectacles and laying down her mending. “You don’t think she’s a little mite crazy, do you, Jane?”

“I don’t think she’s like the rest of us,” responded Jane thoughtfully and with some anxiety in her pleasant face; “but whether it’s for the better or the worse I can’t hardly tell till she grows up. She’s got the making of ‘most anything in her, Rebecca has; but I feel sometimes as if we were not fitted to cope with her.”

“Stuff an’ nonsense!” said Miranda “Speak for yourself. I feel fitted to cope with any child that ever was born int’ the world!”

“I know you do, Mirandy; but that don’t make you so,” returned Jane with a smile.

The habit of speaking her mind freely was certainly growing on Jane to an altogether terrifying extent.

Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm Chapter 10: Rainbow Bridges

Uncle Jerry coughed and stirred in his chair a good deal during Rebecca’s recital, but he carefully concealed any undue feeling of sympathy, just muttering, “Poor little soul! We’ll see what we can do for her!”

“You will take me to Maplewood, won’t you, Mr. Cobb?” begged Rebecca piteously.

“Don’t you fret a mite,” he answered, with a crafty little notion at the back of his mind; “I’ll see the lady passenger through somehow. Now take a bite o’ somethin’ to eat, child. Spread some o’ that tomato preserve on your bread; draw up to the table. How’d you like to set in mother’s place an’ pour me out another cup o’ hot tea?”

Mr. Jeremiah Cobb’s mental machinery was simple, and did not move very smoothly save when propelled by his affection or sympathy. In the present case these were both employed to his advantage, and mourning his stupidity and praying for some flash of inspiration to light his path, he blundered along, trusting to Providence.

Rebecca, comforted by the old man’s tone, and timidly enjoying the dignity of sitting in Mrs. Cobb’s seat and lifting the blue china teapot, smiled faintly, smoothed her hair, and dried her eyes.

“I suppose your mother’ll be terrible glad to see you back again?” queried Mr. Cobb.

A tiny fear—just a baby thing—in the bottom of Rebecca’s heart stirred and grew larger the moment it was touched with a question. “She won’t like it that I ran away, I s’pose, and she’ll be sorry that I couldn’t please aunt Mirandy; but I’ll make her understand, just as I did you.”

“I s’pose she was thinkin’ o’ your schoolin’, lettin’ you come down here; but land! you can go to school in Temperance, I s’pose?”

“There’s only two months’ school now in Temperance, and the farm ‘s too far from all the other schools.”

“Oh well! there’s other things in the world beside edjercation,” responded uncle Jerry, attacking a piece of apple pie.

“Ye—es; though mother thought that was going to be the making of me,” returned Rebecca sadly, giving a dry little sob as she tried to drink her tea.

“It’ll be nice for you to be all together again at the farm—such a house full o’ children!” remarked the dear old deceiver, who longed for nothing so much as to cuddle and comfort the poor little creature.

“It’s too full—that’s the trouble. But I’ll make Hannah come to Riverboro in my place.”

“S’pose Mirandy ‘n’ Jane’ll have her? I should be ‘most afraid they wouldn’t. They’ll be kind o’ mad at your goin’ home, you know, and you can’t hardly blame ’em.”

This was quite a new thought, that the brick house might be closed to Hannah, since she, Rebecca, had turned her back upon its cold hospitality.

“How is this school down here in Riverboro—pretty good?” inquired uncle Jerry, whose brain was working with an altogether unaccustomed rapidity,—so much so that it almost terrified him.

“Oh, it’s a splendid school! And Miss Dearborn is a splendid teacher!”

“You like her, do you? Well, you’d better believe she returns the compliment. Mother was down to the store this afternoon buyin’ liniment for Seth Strout, an’ she met Miss Dearborn on the bridge. They got to talkin’ ’bout school, for mother has summer-boarded a lot o’ the schoolmarms, an’ likes ’em. ‘How does the little Temperance girl git along?’ asks mother. ‘Oh, she’s the best scholar I have!’ says Miss Dearborn. ‘I could teach school from sunup to sundown if scholars was all like Rebecca Randall,’ says she.”

“Oh, Mr. Cobb, did she say that?” glowed Rebecca, her face sparkling and dimpling in an instant. “I’ve tried hard all the time, but I’ll study the covers right off of the books now.”

“You mean you would if you’d ben goin’ to stay here,” interposed uncle Jerry. “Now ain’t it too bad you’ve jest got to give it all up on account o’ your aunt Mirandy? Well, I can’t hardly blame ye. She’s cranky an’ she’s sour; I should think she’d been nussed on bonny-clabber an’ green apples. She needs bearin’ with; an’ I guess you ain’t much on patience, be ye?”

“Not very much,” replied Rebecca dolefully.

“If I’d had this talk with ye yesterday,” pursued Mr. Cobb, “I believe I’d have advised ye different. It’s too late now, an’ I don’t feel to say you’ve been all in the wrong; but if ‘t was to do over again, I’d say, well, your aunt Mirandy gives you clothes and board and schoolin’ and is goin’ to send you to Wareham at a big expense. She’s terrible hard to get along with, an’ kind o’ heaves benefits at your head, same ‘s she would bricks; but they’re benefits jest the same, an’ maybe it’s your job to kind o’ pay for ’em in good behavior. Jane’s a little bit more easy goin’ than Mirandy, ain’t she, or is she just as hard to please?”

“Oh, aunt Jane and I get along splendidly,” exclaimed Rebecca; “she’s just as good and kind as she can be, and I like her better all the time. I think she kind of likes me, too; she smoothed my hair once. I’d let her scold me all day long, for she understands; but she can’t stand up for me against aunt Mirandy; she’s about as afraid of her as I am.”

“Jane’ll be real sorry tomorrow to find you’ve gone away, I guess; but never mind, it can’t be helped. If she has a kind of a dull time with Mirandy, on account o’ her bein’ so sharp, why of course she’d set great store by your comp’ny. Mother was talkin’ with her after prayer meetin’ the other night. ‘You wouldn’t know the brick house, Sarah,’ says Jane. ‘I’m keepin’ a sewin’ school, an’ my scholar has made three dresses. What do you think o’ that,’ says she, ‘for an old maid’s child? I’ve taken a class in Sunday school,’ says Jane, ‘an’ think o’ renewin’ my youth an’ goin’ to the picnic with Rebecca,’ says she; an’ mother declares she never see her look so young ‘n’ happy.”

There was a silence that could be felt in the little kitchen; a silence only broken by the ticking of the tall clock and the beating of Rebecca’s heart, which, it seemed to her, almost drowned the voice of the clock. The rain ceased, a sudden rosy light filled the room, and through the window a rainbow arch could be seen spanning the heavens like a radiant bridge. Bridges took one across difficult places, thought Rebecca, and uncle Jerry seemed to have built one over her troubles and given her strength to walk.

“The shower ‘s over,” said the old man, filling his pipe; “it’s cleared the air, washed the face o’ the earth nice an’ clean, an’ everything to-morrer will shine like a new pin—when you an’ I are drivin’ up river.”

Rebecca pushed her cup away, rose from the table, and put on her hat and jacket quietly. “I’m not going to drive up river, Mr. Cobb,” she said. “I’m going to stay here and—catch bricks; catch ’em without throwing ’em back, too. I don’t know as aunt Mirandy will take me in after I’ve run away, but I’m going back now while I have the courage. You wouldn’t be so good as to go with me, would you, Mr. Cobb?”

“You’d better b’lieve your uncle Jerry don’t propose to leave till he gits this thing fixed up,” cried the old man delightedly. “Now you’ve had all you can stan’ tonight, poor little soul, without gettin’ a fit o’ sickness; an’ Mirandy’ll be sore an’ cross an’ in no condition for argument; so my plan is jest this: to drive you over to the brick house in my top buggy; to have you set back in the corner, an’ I git out an’ go to the side door; an’ when I git your aunt Mirandy ‘n’ aunt Jane out int’ the shed to plan for a load o’ wood I’m goin’ to have hauled there this week, you’ll slip out o’ the buggy and go upstairs to bed. The front door won’t be locked, will it?”

“Not this time of night,” Rebecca answered; “not till aunt Mirandy goes to bed; but oh! what if it should be?”

“Well, it won’t; an’ if ‘t is, why we’ll have to face it out; though in my opinion there’s things that won’t bear facin’ out an’ had better be settled comfortable an’ quiet. You see you ain’t run away yet; you’ve only come over here to consult me ’bout runnin’ away, an’ we’ve concluded it ain’t worth the trouble. The only real sin you’ve committed, as I figure it out, was in comin’ here by the winder when you’d ben sent to bed. That ain’t so very black, an’ you can tell your aunt Jane ’bout it come Sunday, when she’s chock full o’ religion, an’ she can advise you when you’d better tell your aunt Mirandy. I don’t believe in deceivin’ folks, but if you’ve had hard thoughts you ain’t obleeged to own ’em up; take ’em to the Lord in prayer, as the hymn says, and then don’t go on having ’em. Now come on; I’m all hitched up to go over to the post office; don’t forget your bundle; ‘it’s always a journey, mother, when you carry a nightgown;’ them ‘s the first words your uncle Jerry ever heard you say! He didn’t think you’d be bringin’ your nightgown over to his house. Step in an’ curl up in the corner; we ain’t goin’ to let folks see little runaway gals, ’cause they’re goin’ back to begin all over ag’in!”

When Rebecca crept upstairs, and undressing in the dark finally found herself in her bed that night, though she was aching and throbbing in every nerve, she felt a kind of peace stealing over her. She had been saved from foolishness and error; kept from troubling her poor mother; prevented from angering and mortifying her aunts.

Her heart was melted now, and she determined to win aunt Miranda’s approval by some desperate means, and to try and forget the one thing that rankled worst, the scornful mention of her father, of whom she thought with the greatest admiration, and whom she had not yet heard criticized; for such sorrows and disappointments as Aurelia Randall had suffered had never been communicated to her children.

It would have been some comfort to the bruised, unhappy little spirit to know that Miranda Sawyer was passing an uncomfortable night, and that she tacitly regretted her harshness, partly because Jane had taken such a lofty and virtuous position in the matter. She could not endure Jane’s disapproval, although she would never have confessed to such a weakness.

As uncle Jerry drove homeward under the stars, well content with his attempts at keeping the peace, he thought wistfully of the touch of Rebecca’s head on his knee, and the rain of her tears on his hand; of the sweet reasonableness of her mind when she had the matter put rightly before her; of her quick decision when she had once seen the path of duty; of the touching hunger for love and understanding that were so characteristic in her. “Lord A’mighty!” he ejaculated under his breath, “Lord A’mighty! to hector and abuse a child like that one! ‘T ain’t abuse exactly, I know, or ‘t wouldn’t be to some o’ your elephant-hided young ones; but to that little tender will-o’-the-wisp a hard word ‘s like a lash. Mirandy Sawyer would be a heap better woman if she had a little gravestone to remember, same’s mother ‘n’ I have.”

“I never see a child improve in her work as Rebecca has today,” remarked Miranda Sawyer to Jane on Saturday evening. “That settin’ down I gave her was probably just what she needed, and I daresay it’ll last for a month.”

“I’m glad you’re pleased,” returned Jane. “A cringing worm is what you want, not a bright, smiling child. Rebecca looks to me as if she’d been through the Seven Years’ War. When she came downstairs this morning it seemed to me she’d grown old in the night. If you follow my advice, which you seldom do, you’ll let me take her and Emma Jane down beside the river tomorrow afternoon and bring Emma Jane home to a good Sunday supper. Then if you’ll let her go to Milltown with the Cobbs on Wednesday, that’ll hearten her up a little and coax back her appetite. Wednesday’s a holiday on account of Miss Dearborn’s going home to her sister’s wedding, and the Cobbs and Perkinses want to go down to the Agricultural Fair.”

Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm Chapter 9: Ashes of Roses

“There she is, over an hour late; a little more an’ she’d ‘a’ been caught in a thunder shower, but she’d never look ahead,” said Miranda to Jane; “and added to all her other iniquities, if she ain’t rigged out in that new dress, steppin’ along with her father’s dancin’-school steps, and swingin’ her parasol for all the world as if she was play-actin’. Now I’m the oldest, Jane, an’ I intend to have my say out; if you don’t like it you can go into the kitchen till it’s over. Step right in here, Rebecca; I want to talk to you. What did you put on that good new dress for, on a school day, without permission?”

“I had intended to ask you at noontime, but you weren’t at home, so I couldn’t,” began Rebecca.

“You did no such a thing; you put it on because you was left alone, though you knew well enough I wouldn’t have let you.”

“If I’d been certain you wouldn’t have let me I’d never have done it,” said Rebecca, trying to be truthful; “but I wasn’t certain, and it was worth risking. I thought perhaps you might, if you knew it was almost a real exhibition at school.”

“Exhibition!” exclaimed Miranda scornfully; “you are exhibition enough by yourself, I should say. Was you exhibitin’ your parasol?”

“The parasol was silly,” confessed Rebecca, hanging her head; “but it’s the only time in my whole life when I had anything to match it, and it looked so beautiful with the pink dress! Emma Jane and I spoke a dialogue about a city girl and a country girl, and it came to me just the minute before I started how nice it would come in for the city girl; and it did. I haven’t hurt my dress a mite, aunt Mirandy.”

“It’s the craftiness and underhandedness of your actions that’s the worst,” said Miranda coldly. “And look at the other things you’ve done! It seems as if Satan possessed you! You went up the front stairs to your room, but you didn’t hide your tracks, for you dropped your handkerchief on the way up. You left the screen out of your bedroom window for the flies to come in all over the house. You never cleared away your lunch nor set away a dish, and you left the side door unlocked from half past twelve to three o’clock, so ‘t anybody could ‘a’ come in and stolen what they liked!”

Rebecca sat down heavily in her chair as she heard the list of her transgressions. How could she have been so careless? The tears began to flow now as she attempted to explain sins that never could be explained or justified.

“Oh, I’m so sorry!” she faltered. “I was trimming the schoolroom, and got belated, and ran all the way home. It was hard getting into my dress alone, and I hadn’t time to eat but a mouthful, and just at the last minute, when I honestly—honestly—would have thought about clearing away and locking up, I looked at the clock and knew I could hardly get back to school in time to form in the line; and I thought how dreadful it would be to go in late and get my first black mark on a Friday afternoon, with the minister’s wife and the doctor’s wife and the school committee all there!”

“Don’t wail and carry on now; it’s no good cryin’ over spilt milk,” answered Miranda. “An ounce of good behavior is worth a pound of repentance. Instead of tryin’ to see how little trouble you can make in a house that ain’t your own home, it seems as if you tried to see how much you could put us out. Take that rose out o’ your dress and let me see the spot it’s made on your yoke, an’ the rusty holes where the wet pin went in. No, it ain’t; but it’s more by luck than forethought. I ain’t got any patience with your flowers and frizzled-out hair and furbelows an’ airs an’ graces, for all the world like your Miss-Nancy father.”

Rebecca lifted her head in a flash. “Look here, aunt Mirandy, I’ll be as good as I know how to be. I’ll mind quick when I’m spoken to and never leave the door unlocked again, but I won’t have my father called names. He was a p-perfectly l-lovely father, that’s what he was, and it’s mean to call him Miss Nancy!”

“Don’t you dare answer me back that impertinent way, Rebecca, tellin’ me I’m mean; your father was a vain, foolish, shiftless man, an’ you might as well hear it from me as anybody else; he spent your mother’s money and left her with seven children to provide for.”

“It’s s-something to leave s-seven nice children,” sobbed Rebecca.

“Not when other folks have to help feed, clothe, and educate ’em,” responded Miranda. “Now you step upstairs, put on your nightgown, go to bed, and stay there till tomorrow mornin’. You’ll find a bowl o’ crackers an’ milk on your bureau, an’ I don’t want to hear a sound from you till breakfast time. Jane, run an’ take the dish towels off the line and shut the shed doors; we’re goin’ to have a terrible shower.”

“We’ve had it, I should think,” said Jane quietly, as she went to do her sister’s bidding. “I don’t often speak my mind, Mirandy; but you ought not to have said what you did about Lorenzo. He was what he was, and can’t be made any different; but he was Rebecca’s father, and Aurelia always says he was a good husband.”

Miranda had never heard the proverbial phrase about the only “good Indian,” but her mind worked in the conventional manner when she said grimly, “Yes, I’ve noticed that dead husbands are usually good ones; but the truth needs an airin’ now and then, and that child will never amount to a hill o’ beans till she gets some of her father trounced out of her. I’m glad I said just what I did.”

“I daresay you are,” remarked Jane, with what might be described as one of her annual bursts of courage; “but all the same, Mirandy, it wasn’t good manners, and it wasn’t good religion!”

The clap of thunder that shook the house just at that moment made no such peal in Miranda Sawyer’s ears as Jane’s remark made when it fell with a deafening roar on her conscience.

Perhaps after all it is just as well to speak only once a year and then speak to the purpose.

Rebecca mounted the back stairs wearily, closed the door of her bedroom, and took off the beloved pink gingham with trembling fingers. Her cotton handkerchief was rolled into a hard ball, and in the intervals of reaching the more difficult buttons that lay between her shoulder blades and her belt, she dabbed her wet eyes carefully, so that they should not rain salt water on the finery that had been worn at such a price. She smoothed it out carefully, pinched up the white ruffle at the neck, and laid it away in a drawer with an extra little sob at the roughness of life. The withered pink rose fell on the floor. Rebecca looked at it and thought to herself, “Just like my happy day!” Nothing could show more clearly the kind of child she was than the fact that she instantly perceived the symbolism of the rose, and laid it in the drawer with the dress as if she were burying the whole episode with all its sad memories. It was a child’s poetic instinct with a dawning hint of woman’s sentiment in it.

She braided her hair in the two accustomed pigtails, took off her best shoes (which had happily escaped notice), with all the while a fixed resolve growing in her mind, that of leaving the brick house and going back to the farm. She would not be received there with open arms, there was no hope of that, but she would help her mother about the house and send Hannah to Riverboro in her place. “I hope she’ll like it!” she thought in a momentary burst of vindictiveness. She sat by the window trying to make some sort of plan, watching the lightning play over the hilltop and the streams of rain chasing each other down the lightning rod. And this was the day that had dawned so joyfully! It had been a red sunrise, and she had leaned on the window sill studying her lesson and thinking what a lovely world it was. And what a golden morning! The changing of the bare, ugly little schoolroom into a bower of beauty; Miss Dearborn’s pleasure at her success with the Simpson twins’ recitation; the privilege of decorating the blackboard; the happy thought of drawing Columbia from the cigar box; the intoxicating moment when the school clapped her! And what an afternoon! How it went on from glory to glory, beginning with Emma Jane’s telling her, Rebecca Randall, that she was as “handsome as a picture.”

She lived through the exercises again in memory, especially her dialogue with Emma Jane and her inspiration of using the bough-covered stove as a mossy bank where the country girl could sit and watch her flocks. This gave Emma Jane a feeling of such ease that she never recited better; and how generous it was of her to lend the garnet ring to the city girl, fancying truly how it would flash as she furled her parasol and approached the awe-stricken shepherdess! She had thought aunt Miranda might be pleased that the niece invited down from the farm had succeeded so well at school; but no, there was no hope of pleasing her in that or in any other way. She would go to Maplewood on the stage next day with Mr. Cobb and get home somehow from cousin Ann’s. On second thoughts her aunts might not allow it. Very well, she would slip away now and see if she could stay all night with the Cobbs and be off next morning before breakfast.

Rebecca never stopped long to think, more ‘s the pity, so she put on her oldest dress and hat and jacket, then wrapped her nightdress, comb, and toothbrush in a bundle and dropped it softly out of the window. Her room was in the L and her window at no very dangerous distance from the ground, though had it been, nothing could have stopped her at that moment. Somebody who had gone on the roof to clean out the gutters had left a cleat nailed to the side of the house about halfway between the window and the top of the back porch. Rebecca heard the sound of the sewing machine in the dining room and the chopping of meat in the kitchen; so knowing the whereabouts of both her aunts, she scrambled out of the window, caught hold of the lightning rod, slid down to the helpful cleat, jumped to the porch, used the woodbine trellis for a ladder, and was flying up the road in the storm before she had time to arrange any details of her future movements.

Jeremiah Cobb sat at his lonely supper at the table by the kitchen window. “Mother,” as he with his old-fashioned habits was in the habit of calling his wife, was nursing a sick neighbor. Mrs. Cobb was mother only to a little headstone in the churchyard, where reposed “Sarah Ann, beloved daughter of Jeremiah and Sarah Cobb, aged seventeen months;” but the name of mother was better than nothing, and served at any rate as a reminder of her woman’s crown of blessedness.

The rain still fell, and the heavens were dark, though it was scarcely five o’clock. Looking up from his “dish of tea,” the old man saw at the open door a very figure of woe. Rebecca’s face was so swollen with tears and so sharp with misery that for a moment he scarcely recognized her. Then when he heard her voice asking, “Please may I come in, Mr. Cobb?” he cried, “Well I vow! It’s my little lady passenger! Come to call on old uncle Jerry and pass the time o’ day, have ye? Why, you’re wet as sops. Draw up to the stove. I made a fire, hot as it was, thinkin’ I wanted somethin’ warm for my supper, bein’ kind o’ lonesome without mother. She’s settin’ up with Seth Strout tonight. There, we’ll hang your soppy hat on the nail, put your jacket over the chair rail, an’ then you turn your back to the stove an’ dry yourself good.”

Uncle Jerry had never before said so many words at a time, but he had caught sight of the child’s red eyes and tear-stained cheeks, and his big heart went out to her in her trouble, quite regardless of any circumstances that might have caused it.

Rebecca stood still for a moment until uncle Jerry took his seat again at the table, and then, unable to contain herself longer, cried, “Oh, Mr. Cobb, I’ve run away from the brick house, and I want to go back to the farm. Will you keep me tonight and take me up to Maplewood in the stage? I haven’t got any money for my fare, but I’ll earn it somehow afterwards.”

“Well, I guess we won’t quarrel ’bout money, you and me,” said the old man; “and we’ve never had our ride together, anyway, though we allers meant to go down river, not up.”

“I shall never see Milltown now!” sobbed Rebecca.

“Come over here side o’ me an’ tell me all about it,” coaxed uncle Jerry. “Jest set down on that there wooden cricket an’ out with the whole story.”

Rebecca leaned her aching head against Mr. Cobb’s homespun knee and recounted the history of her trouble. Tragic as that history seemed to her passionate and undisciplined mind, she told it truthfully and without exaggeration.

Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm Chapter 16: Seasons Of Growth

The days flew by; as summer had melted into autumn so autumn had given place to winter. Life in the brick house had gone on more placidly of late, for Rebecca was honestly trying to be more careful in the performance of her tasks and duties as well as more quiet in her plays, and she was slowly learning the power of the soft answer in turning away wrath.

Miranda had not had, perhaps, quite as many opportunities in which to lose her temper, but it is only just to say that she had not fully availed herself of all that had offered themselves.

There had been one outburst of righteous wrath occasioned by Rebecca’s over-hospitable habits, which were later shown in a still more dramatic and unexpected fashion.

On a certain Friday afternoon she asked her aunt Miranda if she might take half her bread and milk upstairs to a friend.

“What friend have you got up there, for pity’s sake?” demanded aunt Miranda.

“The Simpson baby, come to stay over Sunday; that is, if you’re willing, Mrs. Simpson says she is. Shall I bring her down and show her? She’s dressed in an old dress of Emma Jane’s and she looks sweet.”

“You can bring her down, but you can’t show her to me! You can smuggle her out the way you smuggled her in and take her back to her mother. Where on earth do you get your notions, borrowing a baby for Sunday!”

“You’re so used to a house without a baby you don’t know how dull it is,” sighed Rebecca resignedly, as she moved towards the door; “but at the farm there was always a nice fresh one to play with and cuddle. There were too many, but that’s not half as bad as none at all. Well, I’ll take her back. She’ll be dreadfully disappointed and so will Mrs. Simpson. She was planning to go to Milltown.”

“She can un-plan then,” observed Miss Miranda.

“Perhaps I can go up there and take care of the baby?” suggested Rebecca. “I brought her home so ‘t I could do my Saturday work just the same.”

“You’ve got enough to do right here, without any borrowed babies to make more steps. Now, no answering back, just give the child some supper and carry it home where it belongs.”

“You don’t want me to go down the front way, hadn’t I better just come through this room and let you look at her? She has yellow hair and big blue eyes! Mrs. Simpson says she takes after her father.”

Miss Miranda smiled acidly as she said she couldn’t take after her father, for he’d take anything there was before she got there!

Aunt Jane was in the linen closet upstairs, sorting out the clean sheets and pillow cases for Saturday, and Rebecca sought comfort from her.

“I brought the Simpson baby home, aunt Jane, thinking it would help us over a dull Sunday, but aunt Miranda won’t let her stay. Emma Jane has the promise of her next Sunday and Alice Robinson the next. Mrs. Simpson wanted I should have her first because I’ve had so much experience in babies. Come in and look at her sitting up in my bed, aunt Jane! Isn’t she lovely? She’s the fat, gurgly kind, not thin and fussy like some babies, and I thought I was going to have her to undress and dress twice each day. Oh dear! I wish I could have a printed book with everything set down in it that I could do, and then I wouldn’t get disappointed so often.”

“No book could be printed that would fit you, Rebecca,” answered aunt Jane, “for nobody could imagine beforehand the things you’d want to do. Are you going to carry that heavy child home in your arms?”

“No, I’m going to drag her in the little soap-wagon. Come, baby! Take your thumb out of your mouth and come to ride with Becky in your go-cart.” She stretched out her strong young arms to the crowing baby, sat down in a chair with the child, turned her upside down unceremoniously, took from her waistband and scornfully flung away a crooked pin, walked with her (still in a highly reversed position) to the bureau, selected a large safety pin, and proceeded to attach her brief red flannel petticoat to a sort of shirt that she wore. Whether flat on her stomach, or head down, heels in the air, the Simpson baby knew she was in the hands of an expert, and continued gurgling placidly while aunt Jane regarded the pantomime with a kind of dazed awe.

“Bless my soul, Rebecca,” she ejaculated, “it beats all how handy you are with babies!”

“I ought to be; I’ve brought up three and a half of ’em,” Rebecca responded cheerfully, pulling up the infant Simpson’s stockings.

“I should think you’d be fonder of dolls than you are,” said Jane.

“I do like them, but there’s never any change in a doll; it’s always the same everlasting old doll, and you have to make believe it’s cross or sick, or it loves you, or can’t bear you. Babies are more trouble, but nicer.”

Miss Jane stretched out a thin hand with a slender, worn band of gold on the finger, and the baby curled her dimpled fingers round it and held it fast.

“You wear a ring on your engagement finger, don’t you, aunt Jane? Did you ever think about getting married?”

“Yes, dear, long ago.”

“What happened, aunt Jane?”

“He died—just before.”

“Oh!” And Rebecca’s eyes grew misty.

“He was a soldier and he died of a gunshot wound, in a hospital, down South.”

“Oh! aunt Jane!” softly. “Away from you?”

“No, I was with him.”

“Was he young?”

“Yes; young and brave and handsome, Rebecca; he was Mr. Carter’s brother Tom.”

“Oh! I’m so glad you were with him! Wasn’t he glad, aunt Jane?”

Jane looked back across the half-forgotten years, and the vision of Tom’s gladness flashed upon her: his haggard smile, the tears in his tired eyes, his outstretched arms, his weak voice saying, “Oh, Jenny! Dear Jenny! I’ve wanted you so, Jenny!” It was too much! She had never breathed a word of it before to a human creature, for there was no one who would have understood. Now, in a shamefaced way, to hide her brimming eyes, she put her head down on the young shoulder beside her, saying, “It was hard, Rebecca!”

The Simpson baby had cuddled down sleepily in Rebecca’s lap, leaning her head back and sucking her thumb contentedly. Rebecca put her cheek down until it touched her aunt’s gray hair and softly patted her, as she said, “I’m sorry, aunt Jane!”

The girl’s eyes were soft and tender and the heart within her stretched a little and grew; grew in sweetness and intuition and depth of feeling. It had looked into another heart, felt it beat, and heard it sigh; and that is how all hearts grow.

Episodes like these enlivened the quiet course of everyday existence, made more quiet by the departure of Dick Carter, Living Perkins, and Huldah Meserve for Wareham, and the small attendance at the winter school, from which the younger children of the place stayed away during the cold weather.

Life, however, could never be thoroughly dull or lacking in adventure to a child of Rebecca’s temperament. Her nature was full of adaptability, fluidity, receptivity. She made friends everywhere she went, and snatched up acquaintances in every corner.

It was she who ran to the shed door to take the dish to the “meat man” or “fish man;” she who knew the family histories of the itinerant fruit venders and tin peddlers; she who was asked to take supper or pass the night with children in neighboring villages—children of whose parents her aunts had never so much as heard. As to the nature of these friendships, which seemed so many to the eye of the superficial observer, they were of various kinds, and while the girl pursued them with enthusiasm and ardor, they left her unsatisfied and heart-hungry; they were never intimacies such as are so readily made by shallow natures. She loved Emma Jane, but it was a friendship born of propinquity and circumstance, not of true affinity. It was her neighbor’s amiability, constancy, and devotion that she loved, and although she rated these qualities at their true value, she was always searching beyond them for intellectual treasures; searching and never finding, for although Emma Jane had the advantage in years she was still immature. Huldah Meserve had an instinctive love of fun which appealed to Rebecca; she also had a fascinating knowledge of the world, from having visited her married sisters in Milltown and Portland; but on the other hand there was a certain sharpness and lack of sympathy in Huldah which repelled rather than attracted. With Dick Carter she could at least talk intelligently about lessons. He was a very ambitious boy, full of plans for his future, which he discussed quite freely with Rebecca, but when she broached the subject of her future his interest sensibly lessened. Into the world of the ideal Emma Jane, Huldah, and Dick alike never seemed to have peeped, and the consciousness of this was always a fixed gulf between them and Rebecca.

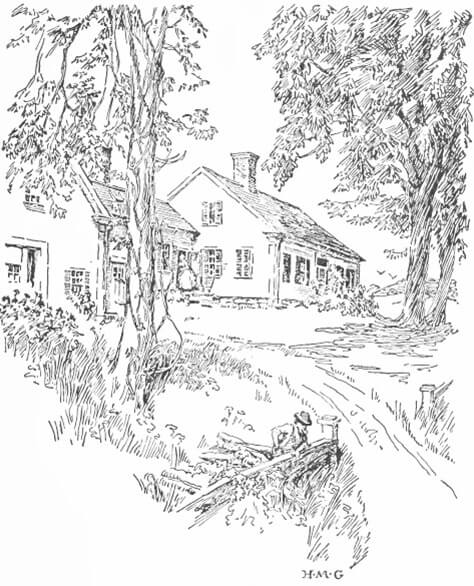

Uncle Jerry’s House

Uncle Jerry’s House

“Uncle Jerry” and “aunt Sarah” Cobb were dear friends of quite another sort, a very satisfying and perhaps a somewhat dangerous one. A visit from Rebecca always sent them into a twitter of delight. Her merry conversation and quaint comments on life in general fairly dazzled the old couple, who hung on her lightest word as if it had been a prophet’s utterance; and Rebecca, though she had had no previous experience, owned to herself a perilous pleasure in being dazzling, even to a couple of dear humdrum old people like Mr. and Mrs. Cobb.

Aunt Sarah flew to the pantry or cellar whenever Rebecca’s slim little shape first appeared on the crest of the hill, and a jelly tart or a frosted cake was sure to be forthcoming. The sight of old uncle Jerry’s spare figure in its clean white shirt sleeves, whatever the weather, always made Rebecca’s heart warm when she saw him peer longingly from the kitchen window. Before the snow came, many was the time he had come out to sit on a pile of boards at the gate, to see if by any chance she was mounting the hill that led to their house.

In the autumn Rebecca was often the old man’s companion while he was digging potatoes or shelling beans, and now in the winter, when a younger man was driving the stage, she sometimes stayed with him while he did his evening milking. It is safe to say that he was the only creature in Riverboro who possessed Rebecca’s entire confidence; the only being to whom she poured out her whole heart, with its wealth of hopes, and dreams, and vague ambitions. At the brick house she practiced scales and exercises, but at the Cobbs’ cabinet organ she sang like a bird, improvising simple accompaniments that seemed to her ignorant auditors nothing short of marvelous. Here she was happy, here she was loved, here she was drawn out of herself and admired and made much of. But, she thought, if there were somebody who not only loved but understood; who spoke her language, comprehended her desires, and responded to her mysterious longings! Perhaps in the big world of Wareham there would be people who thought and dreamed and wondered as she did.

In reality Jane did not understand her niece very much better than Miranda; the difference between the sisters was, that while Jane was puzzled, she was also attracted, and when she was quite in the dark for an explanation of some quaint or unusual action she was sympathetic as to its possible motive and believed the best. A greater change had come over Jane than over any other person in the brick house, but it had been wrought so secretly, and concealed so religiously, that it scarcely appeared to the ordinary observer. Life had now a motive utterly lacking before. Breakfast was not eaten in the kitchen, because it seemed worth while, now that there were three persons, to lay the cloth in the dining room; it was also a more bountiful meal than of yore, when there was no child to consider. The morning was made cheerful by Rebecca’s start for school, the packing of the luncheon basket, the final word about umbrella, waterproof, or rubbers; the parting admonition and the unconscious waiting at the window for the last wave of the hand.

She found herself taking pride in Rebecca’s improved appearance, her rounder throat and cheeks, and her better color; she was wont to mention the length of Rebecca’s hair and add a word as to its remarkable evenness and luster, at times when Mrs. Perkins grew too diffuse about Emma Jane’s complexion. She threw herself wholeheartedly on her niece’s side when it became a question between a crimson or a brown linsey-woolsey dress, and went through a memorable struggle with her sister concerning the purchase of a red bird for Rebecca’s black felt hat. No one guessed the quiet pleasure that lay hidden in her heart when she watched the girl’s dark head bent over her lessons at night, nor dreamed of her joy it, certain quiet evenings when Miranda went to prayer meeting; evenings when Rebecca would read aloud “Hiawatha” or “Barbara Frietchie,” “The Bugle Song,” or “The Brook.” Her narrow, humdrum existence bloomed under the dews that fell from this fresh spirit; her dullness brightened under the kindling touch of the younger mind, took fire from the “vital spark of heavenly flame” that seemed always to radiate from Rebecca’s presence.

Rebecca’s idea of being a painter like her friend Miss Ross was gradually receding, owing to the apparently insuperable difficulties in securing any instruction. Her aunt Miranda saw no wisdom in cultivating such a talent, and could not conceive that any money could ever be earned by its exercise, “Hand painted pictures” were held in little esteem in Riverboro, where the cheerful chromo or the dignified steel engraving were respected and valued. There was a slight, a very slight hope, that Rebecca might be allowed a few music lessons from Miss Morton, who played the church cabinet organ, but this depended entirely upon whether Mrs. Morton would decide to accept a hayrack in return for a year’s instruction from her daughter. She had the matter under advisement, but a doubt as to whether or not she would sell or rent her hayfields kept her from coming to a conclusion. Music, in common with all other accomplishments, was viewed by Miss Miranda as a trivial, useless, and foolish amusement, but she allowed Rebecca an hour a day for practice on the old piano, and a little extra time for lessons, if Jane could secure them without payment of actual cash.

The news from Sunnybrook Farm was hopeful rather than otherwise. Cousin Ann’s husband had died, and John, Rebecca’s favorite brother, had gone to be the man of the house to the widowed cousin. He was to have good schooling in return for his care of the horse and cow and barn, and what was still more dazzling, the use of the old doctor’s medical library of two or three dozen volumes. John’s whole heart was set on becoming a country doctor, with Rebecca to keep house for him, and the vision seemed now so true, so near, that he could almost imagine his horse ploughing through snowdrifts on errands of mercy, or, less dramatic but none the less attractive, could see a physician’s neat turncut trundling along the shady country roads, a medicine case between his, Dr. Randall’s, feet, and Miss Rebecca Randall sitting in a black silk dress by his side.

Hannah now wore her hair in a coil and her dresses a trifle below her ankles, these concessions being due to her extreme height. Mark had broken his collar bone, but it was healing well. Little Mira was growing very pretty. There was even a rumor that the projected railroad from Temperance to Plumville might go near the Randall farm, in which case land would rise in value from nothing-at-all an acre to something at least resembling a price. Mrs. Randall refused to consider any improvement in their financial condition as a possibility. Content to work from sunrise to sunset to gain a mere subsistence for her children, she lived in their future, not in her own present, as a mother is wont to do when her own lot seems hard and cheerless.

Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm Chapter 8: Color Of Rose

On the very next Friday after this “dreadfullest fight that ever was seen,” as Bunyan says in Pilgrim’s Progress, there were great doings in the little schoolhouse on the hill. Friday afternoon was always the time chosen for dialogues, songs, and recitations, but it cannot be stated that it was a gala day in any true sense of the word. Most of the children hated “speaking pieces;” hated the burden of learning them, dreaded the danger of breaking down in them.

Miss Dearborn commonly went home with a headache and never left her bed during the rest of the afternoon or evening; and the casual female parent who attended the exercises sat on a front bench with beads of cold sweat on her forehead, listening to the all-too-familiar halts and stammers. Sometimes a bellowing infant who had clean forgotten his verse would cast himself bodily on the maternal bosom and be borne out into the open air, where he was sometimes kissed and occasionally spanked; but in any case the failure added an extra dash of gloom and dread to the occasion.

The advent of Rebecca had somehow infused a new spirit into these hitherto terrible afternoons. She had taught Elijah and Elisha Simpson so that they recited three verses of something with such comical effect that they delighted themselves, the teacher, and the school; while Susan, who lisped, had been provided with a humorous poem in which she impersonated a lisping child. Emma Jane and Rebecca had a dialogue, and the sense of companionship buoyed up Emma Jane and gave her self-reliance.

In fact, Miss Dearborn announced on this particular Friday morning that the exercises promised to be so interesting that she had invited the doctor’s wife, the minister’s wife, two members of the school committee, and a few mothers. Living Perkins was asked to decorate one of the blackboards and Rebecca the other. Living, who was the star artist of the school, chose the map of North America. Rebecca liked better to draw things less realistic, and speedily, before the eyes of the enchanted multitude, there grew under her skillful fingers an American flag done in red, white, and blue chalk, every star in its right place, every stripe fluttering in the breeze. Beside this appeared a figure of Columbia, copied from the top of the cigar box that held the crayons.

Miss Dearborn was delighted. “I propose we give Rebecca a good hand-clapping for such a beautiful picture—one that the whole school may well be proud of!”

The scholars clapped heartily, and Dick Carter, waving his hand, gave a rousing cheer.

Rebecca’s heart leaped for joy, and to her confusion she felt the tears rising in her eyes. She could hardly see the way back to her seat, for in her ignorant lonely little life she had never been singled out for applause, never lauded, nor crowned, as in this wonderful, dazzling moment. If “nobleness enkindleth nobleness,” so does enthusiasm beget enthusiasm, and so do wit and talent enkindle wit and talent.

Alice Robinson proposed that the school should sing ‘Three Cheers for the Red, White, and Blue!’ and when they came to the chorus, all point to Rebecca’s flag. Dick Carter suggested that Living Perkins and Rebecca Randall should sign their names to their pictures, so that the visitors would know who drew them.

Huldah Meserve asked permission to cover the largest holes in the plastered walls with boughs and fill the water pail with wild flowers. Rebecca’s mood was above and beyond all practical details. She sat silent, her heart so full of grateful joy that she could hardly remember the words of her dialogue. At recess she bore herself modestly, notwithstanding her great triumph, while in the general atmosphere of good will the Smellie-Randall hatchet was buried and Minnie gathered maple boughs and covered the ugly stove with them, under Rebecca’s direction.

Miss Dearborn dismissed the morning session at quarter to twelve, so that those who lived near enough could go home for a change of dress. Emma Jane and Rebecca ran nearly every step of the way, from sheer excitement, only stopping to breathe at the stiles.

“Will your aunt Mirandy let you wear your best, or only your buff calico?” asked Emma Jane.

“I think I’ll ask aunt Jane,” Rebecca replied. “Oh! if my pink was only finished! I left aunt Jane making the buttonholes!”

“I’m going to ask my mother to let me wear her garnet ring,” said Emma Jane. “It would look perfectly elegant flashing in the sun when I point to the flag. Goodbye; don’t wait for me going back; I may get a ride.”

Rebecca found the side door locked, but she knew that the key was under the step, and so of course did everybody else in Riverboro, for they all did about the same thing with it. She unlocked the door and went into the dining room to find her lunch laid on the table and a note from aunt Jane saying that they had gone to Moderation with Mrs. Robinson in her carryall. Rebecca swallowed a piece of bread and butter, and flew up the front stairs to her bedroom. On the bed lay the pink gingham dress finished by aunt Jane’s kind hands. Could she, dare she, wear it without asking? Did the occasion justify a new costume, or would her aunts think she ought to keep it for the concert?

“I’ll wear it,” thought Rebecca. “They’re not here to ask, and maybe they wouldn’t mind a bit; it’s only gingham after all, and wouldn’t be so grand if it wasn’t new, and hadn’t tape trimming on it, and wasn’t pink.”

She unbraided her two pigtails, combed out the waves of her hair and tied them back with a ribbon, changed her shoes, and then slipped on the pretty frock, managing to fasten all but the three middle buttons, which she reserved for Emma Jane.

Then her eye fell on her cherished pink sunshade, the exact match, and the girls had never seen it. It wasn’t quite appropriate for school, but she needn’t take it into the room; she would wrap it in a piece of paper, just show it, and carry it coming home. She glanced in the parlor looking-glass downstairs and was electrified at the vision. It seemed almost as if beauty of apparel could go no further than that heavenly pink gingham dress! The sparkle of her eyes, glow of her cheeks, sheen of her falling hair, passed unnoticed in the all-conquering charm of the rose-colored garment. Goodness! it was twenty minutes to one and she would be late. She danced out the side door, pulled a pink rose from a bush at the gate, and covered the mile between the brick house and the seat of learning in an incredibly short time, meeting Emma Jane, also breathless and resplendent, at the entrance.

“Rebecca Randall!” exclaimed Emma Jane, “you’re handsome as a picture!”

“I?” laughed Rebecca “Nonsense! it’s only the pink gingham.”

“You’re not good looking every day,” insisted Emma Jane; “but you’re different somehow. See my garnet ring; mother scrubbed it in soap and water. How on earth did your aunt Mirandy let you put on your brand new dress?”

“They were both away and I didn’t ask,” Rebecca responded anxiously. “Why? Do you think they’d have said no?”

“Miss Mirandy always says no, doesn’t she?” asked Emma Jane.

“Ye—es; but this afternoon is very special—almost like a Sunday school concert.”

“Yes,” assented Emma Jane, “it is, of course; with your name on the board, and our pointing to your flag, and our elegant dialogue, and all that.”

The afternoon was one succession of solid triumphs for everybody concerned. There were no real failures at all, no tears, no parents ashamed of their offspring. Miss Dearborn heard many admiring remarks passed upon her ability, and wondered whether they belonged to her or partly, at least, to Rebecca. The child had no more to do than several others, but she was somehow in the foreground.

It transpired afterwards at various village entertainments that Rebecca couldn’t be kept in the background; it positively refused to hold her. Her worst enemy could not have called her pushing. She was ready and willing and never shy; but she sought for no chances of display and was, indeed, remarkably lacking in self-consciousness, as well as eager to bring others into whatever fun or entertainment there was.

If wherever the MacGregor sat was the head of the table, so in the same way wherever Rebecca stood was the center of the stage. Her clear high treble soared above all the rest in the choruses, and somehow everybody watched her, took note of her gestures, her whole-souled singing, her irrepressible enthusiasm.

Finally it was all over, and it seemed to Rebecca as if she should never be cool and calm again, as she loitered on the homeward path. There would be no lessons to learn tonight, and the vision of helping with the preserves on the morrow had no terrors for her—fears could not draw breath in the radiance that flooded her soul. There were thick gathering clouds in the sky, but she took no note of them save to be glad that she could raise her sunshade. She did not tread the solid ground at all, or have any sense of belonging to the common human family, until she entered the side yard of the brick house and saw her aunt Miranda standing in the open doorway. Then with a rush she came back to earth.

Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm: Chapter 7: Riverboro Secrets

Mr. Simpson spent little time with his family, owing to certain awkward methods of horse-trading, or the “swapping” of farm implements and vehicles of various kinds, operations in which his customers were never long suited. After every successful trade he generally passed a longer or shorter term in jail; for when a poor man without goods or chattels has the inveterate habit of swapping, it follows naturally that he must have something to swap; and having nothing of his own, it follows still more naturally that he must swap something belonging to his neighbors.

Mr. Simpson was absent from the home circle for the moment because he had exchanged the Widow Rideout’s sleigh for Joseph Goodwin’s plough. Goodwin had lately moved to North Edgewood and had never before met the urbane and persuasive Mr. Simpson. The Goodwin plough Mr. Simpson speedily bartered with a man “over Wareham way,” and got in exchange for it an old horse which his owner did not need, as he was leaving town to visit his daughter for a year, Simpson fattened the aged animal, keeping him for several weeks (at early morning or after nightfall) in one neighbor’s pasture after another, and then exchanged him with a Milltown man for a top buggy.