Young George Washington

George Washington was born in a plain, old-fashioned house in Westmoreland County, Virginia, on the twenty-second day of February, 1732. He was sent to what was called an “old field school.” The country schoolhouses in Virginia at that time were built in fields too much worn out to grow anything. Little George Washington went to a school taught by a man named Hobby.

In that day the land in Virginia was left to the oldest son, after the custom in England, for Virginia was an English colony. As George’s elder brother Lawrence was to have the land and be the great gentleman of the family, he had been sent to England for his education. When he got back, with many a strange story of England to tell, George became very proud of him, and Lawrence was equally pleased with his manly little brother. When Lawrence went away as captain, in the regiment raised in America for service in the English army against the Spaniards in the West Indies, George began to think much of a soldier’s life, and to drill the boys in Hobby’s school. There were marches and parades and bloodless battles fought among the tufts of broom-straw in the old field, and in these young George was captain.

This play-captain soon came to be a tall boy. He could run swiftly, and he was a powerful wrestler. The stories of the long jumps he made are almost beyond belief. It was also said that he could throw farther than anybody else. The people of that day went everywhere on horseback, and George was not afraid to get astride of the wildest horse or an unbroken colt. These things proved that he was a strongly built and fearless boy. But a better thing is told of him. He was so just, that his schoolmates used to bring their quarrels for him to settle.

When Washington was eleven years old his father died, but his mother took pains to bring him up with manly ideas. He was now sent to school to a Mr. Williams, from whom he learned reading, writing, and arithmetic. To these were added a little book-keeping and surveying.

George took great pains with all he did. His copybooks have been kept, and they show that his handwriting was very neat. He also wrote out over fifty rules for behavior in company.” You see that he wished to be a gentleman in every way.

His brother Lawrence wanted George to go to sea as a midshipman in the British navy, and George himself liked the plan. But his mother was unwilling to part with him. So he stayed at school until he was sixteen years old.

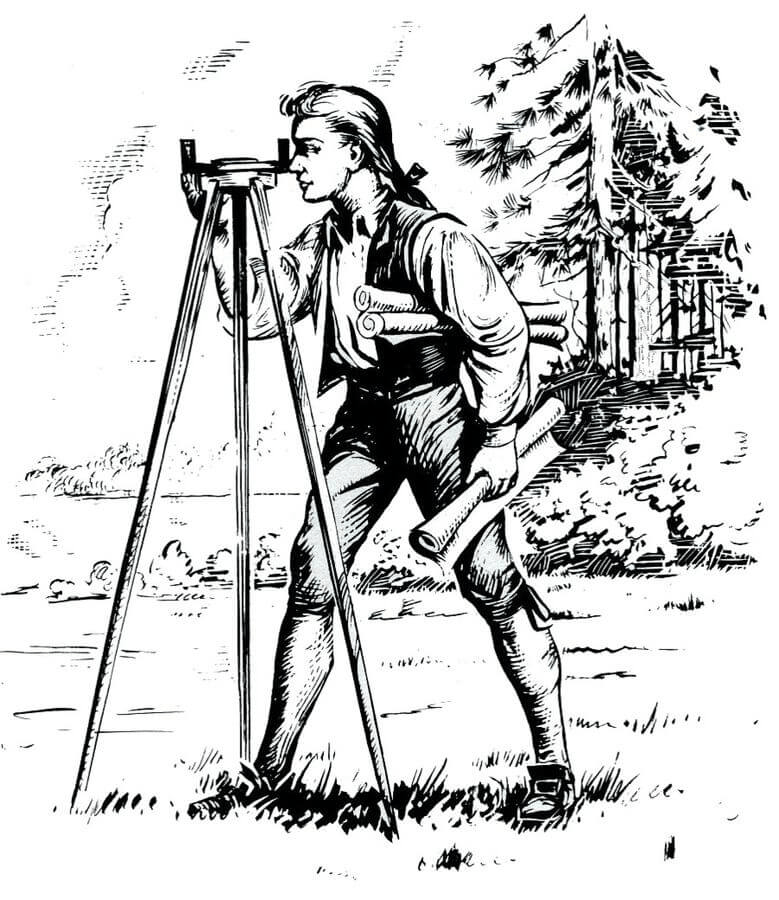

A great deal of the northern part of Virginia at this time belonged to Lord Fairfax, an eccentric nobleman, whose estates included many whole counties. George Washington must have studied his books of surveying very carefully, for he was only a large boy when he was employed to go over beyond the Blue Ridge Mountains and survey some of the wild lands of Lord Fairfax.

So, when he was just sixteen years old, young Washington accepted the offer of Lord Fairfax, and set out for the wilderness. He crossed rough mountains and rode his horse through swollen streams. The settlers’ beds were only masses of straw, with, perhaps, a ragged blanket. But George slept most of the time out under the sky by a campfire, with a little haw straw, or fodder for a bed. Sometimes men and women and children slept around these fires, “like cats and dogs,” as Washington wrote, “and happy is he who gets nearest the fire.” Once the straw on which the young- surveyor was asleep blazed up, and he might have been consumed if one of the party had not waked him in time. Washington must have been a pretty good surveyor, for he received large pay for his work, earning from seven to twenty-one dollars a day, in a time when things were much cheaper than they are now.

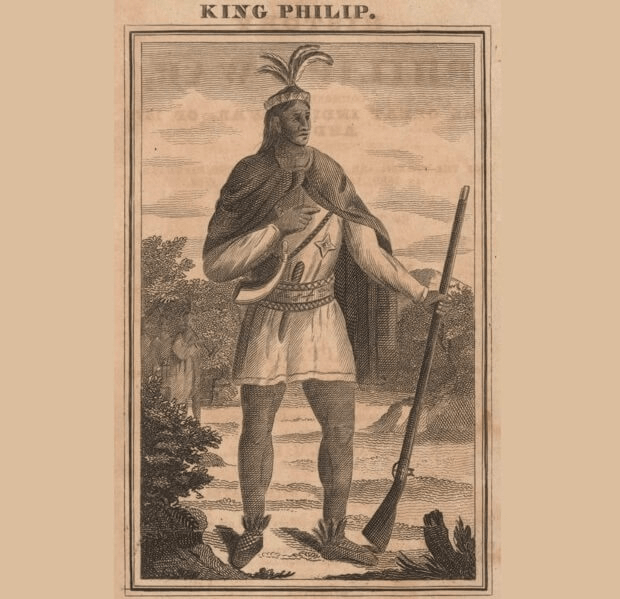

The food of people in the woods was the meat of wild turkey and other game. Every man was his own cook, toasting his meat on a forked stick, and eating it off a chip instead of a plate. Washington led this rough life for three years. It was a good school for a soldier. Here, too, he made his first acquaintance with the American Indians. He saw a party of them dance to the music of a drum made by stretching deer-skin very tightly over the top of a pot half full of water. They also had a rattle, made by putting shot into a gourd. They took pains to tie a piece of horse’s tail to the gourd, so as to see the horse-hair switch to and fro when the gourd was shaken.

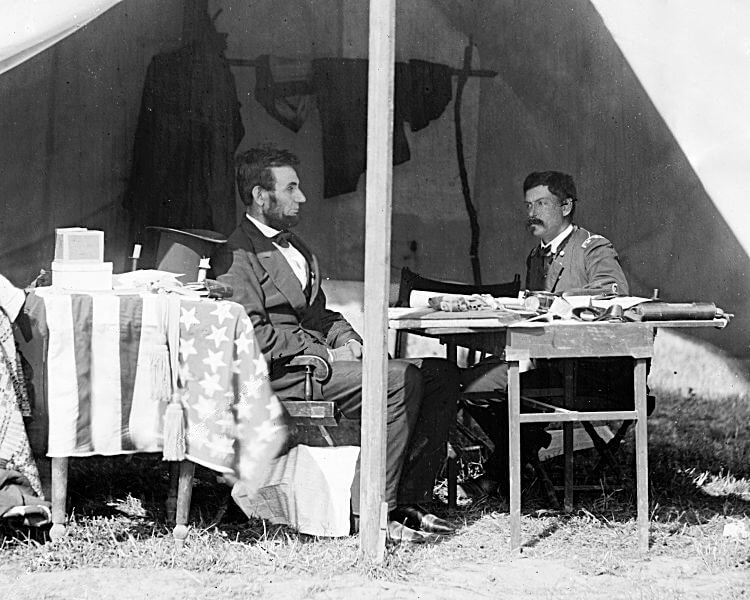

When Washington was but nineteen years old the governor of Virginia made him a major of He took lessons in military drill from an old soldier, and practiced sword exercises under the instruction of a Dutchman named Van Braam. The people in Virginia and the other colonies were looking forward to a war with the French, who in that day had colonies in Canada and Louisiana. They claimed the country west of the Alleghany Mountains. The English colonists had spread over most of the country east of the mountains, and they were beginning to cross the Alleghanies. But the French built forts on the west side of the mountains and stirred up the Indians to prevent the English settlers from coming over into the rich valley of the Ohio River.

The governor of Virginia resolved to send an officer to warn the French that they were on English ground. Who was so fit to go on this hard and dangerous errand as the brave young Major Washington, who knew both the woods and the ways of the Indians? So Washington set out with a few hardy frontiersmen. When at length, after crossing swollen streams and rough mountains, he got over to the Ohio River, where all was wilderness, he called the Indians together and had a big talk with them, at a place called Logtown. He got a chief called “The Half-king,” and some other Indians, to go with him to the French fort.

The French officers had no notion of giving up their fort to the English. They liked this brave and gentlemanly young Major Washington and entertained him well. But they tried to get the Half-king and his Indians to leave Washington and did what they could to keep him from getting safely home again. With a great deal of trouble, he got his Indians away from the French fort at last and started back. Part of the way they traveled in canoes, jumping out into the icy water now and then to lift the canoes over shallow places.

When Washington came to the place where he was to leave the Indians and recross the mountains, his packhorses were found to be so weak that they were unfit for their work. So Major Washington gave up his saddlehorse to carry the baggage. Then he strapped a pack on his back, shouldered his gun, and with a man named Gist set out ahead of the rest of the party.

Washington and Gist had a rascally Indian for guide. When Washington was tired this fellow wished to carry his gun for him, but the young major thought the gun safer in his own hands. At length, as evening came on, the Indian turned suddenly, leveled his gun, and fired on Washington and Gist, in the dark, but without hitting either of them. They seized him before he could reload his gun. Gist wanted to kill him, but Washington thought it better to let him go.

Afraid of being attacked, they now traveled night and day till they got to the Alleghany River. This was full of floating ice, and they tried to cross it on a raft. Washington was pushing the raft with a pole, when the ice caught the pole in such a way as to fling him into the river. He caught hold of the raft and got out again. He and Gist spent the cold night on an island in the river and got ashore in the morning by walking on the ice.

They now stopped at the house of an Indian trader. Nearby was a chief, who was offended that she had not been asked to the council Washington had held with the Indians at Logtown. To make friends, he made her a visit, and presented her with a blanket such as the Indians wear on their shoulders. Washington bought a horse here, and soon got back to the settlements, where the story of the adventures of the young major was told from one plantation to another, producing much excitement.