Engaging Children’s Books, Fun Facts and Delicious Recipes

Children’s Bible books

- For younger kids

- MOTHER STORIES From the Old Testament: This book contains engaging stories from the Old Testament including tales of creation, heroes, and important lessons.

- Mother Stories from the New Testament: “Mother Stories from the New Testament” shares engaging narratives for children, emphasizing faith, kindness, and moral lessons from Jesus’ life.

- For older kids

- THE CHILDREN’S SIX MINUTES by Bruce S. Wright: The Children’s Six Minutes by Bruce S. Wright features a collection of themes exploring growth, kindness, faith, and life’s lessons through various engaging stories and reflections.

- The Wonder Book of Bible Stories: “The Wonder Book of Bible Stories” by Logan Marshall shares simplified biblical narratives for children, conveying essential moral lessons through engaging tales from the Bible.

Children’s books

- Free Online Books for Learning {Here a like where we put all the book for older and younger kids and a book for adults on the Bible}

- For younger kids

- McGuffey Eclectic Primer: textbook focused on early literacy, teaching reading and writing through simple lessons and moral stories for young children.

- McGuffey’s First Eclectic Reader: educational textbook for young readers, combining phonics, sight words, moral lessons, and simple narratives to enhance literacy skills.

- MCGUFFEY’S SECOND ECLECTIC READER: educational book for children, promoting literacy and moral values through engaging prose, poetry, and vocabulary exercises.

- The Real Mother Goose: a collection of nursery rhymes, reflecting childhood’s whimsical essence through well-known verses and engaging illustrations.

- THE GREAT BIG TREASURY OF BEATRIX POTTER: The Great Big Treasury of Beatrix Potter features beloved stories like The Tale of Peter Rabbit and The Tale of Jemima Puddle-Duck, celebrating whimsical animal adventures.

- The Tale of Solomon Owl is a whimsical children’s book by Arthur Scott Bailey, exploring themes of friendship and adventure through Solomon Owl’s humorous encounters with forest animals.

- THE TALE OF JOLLY ROBIN: follows a young bird’s adventures as he learns life skills, values friendship, and explores youthful curiosity through humorous encounters in the wild.

- Peter and Polly Series: The content describes a series of stories for 1st graders featuring Peter and Polly, exploring seasonal adventures, imaginative play, nature, family, and interactions with pets and animals.

- The Adventures of Old Mr. Toad: recounts Old Mr. Toad’s humorous nature-filled journeys, emphasizing lessons on friendship, humility, and personal growth amidst various animal encounters.

- The Wonderful Wizard of Oz: follows Dorothy’s adventures in Oz as she seeks to return home, meeting memorable friends while exploring themes of courage, friendship, and self-discovery.

- For older kids

- Stories of Don Quixote Written Anew for Children retells key adventures from Cervantes’ novel, preserving its spirit while engagingly presenting them for young readers in a cohesive narrative.

- Heidi by Johanna Spyri follows a young girl adapting to life in the Swiss Alps with her grandfather, highlighting themes of family, love, and the power of nature.

- Swiss Family Robinson by Johann David Wyss: is a beloved adventure novel by Johann David Wyss about a Swiss family stranded on a deserted island, relying on their creativity and teamwork to survive and build a new life.

- Rebecca Of Sunnybrook Farm: follows the spirited Rebecca Randall as she navigates life with her aunts in Riverboro, experiencing adventure, growth, and identity exploration.

Children’s history book

- For younger kids

- Great Stories for Little Americans: introduces young readers to American history through engaging tales, fostering national pride and knowledge of heritage via accessible storytelling.

- The Bird-woman of the Lewis and Clark Expedition: A Supplementary Reader for First and Second Grades- tells Sacajawea’s vital role in guiding the explorers, emphasizing her contributions and experiences during this historic journey.

- The Story of Mankind: chronicles human history from prehistory to the modern era, highlighting key events, cultures, and figures that shaped civilization.

- A First Book in American History: A first book in American history: with special reference to the lives and deeds of great Americans. This book chronicles pivotal figures in American history, from Columbus and John Smith to Franklin and Lincoln, highlighting their contributions and the nation’s expansion.

- For older kids

- THE TRUE STORY OF CHRISTOPHER COLUMBUS CALLED THE GREAT ADMIRAL: depicts Columbus’s ambition, challenges, and achievements, inspiring young readers through his exploration and perseverance.

- A History of the United States and its People: The content outlines the early history of the United States, detailing exploration, settlement, colonial life, conflicts, and the events leading to the American Revolution.

- The Boy’s Life of Edison describes Thomas Edison’s early life, emphasizing his curiosity, hard work, and exploratory spirit that shaped him as an inventor.

- The Little Book of the War outlines the events and consequences of World War I, detailing causes, key battles, and the involvement of various nations, including America.

Poem and stories

- THE PLYMOUTH HARVEST by Governor Bradford

- The Real Mother Goose Poems Book: a collection of nursery rhymes, reflecting childhood’s whimsical essence through well-known verses and engaging illustrations.

- Top Poems for Children by Famous Authors: A list of children’s poems organized by author, with future additions anticipated, includes works by notable poets and authors. [Coming soon]

- Poems and stories by Bell: Bell, a young poet, shares her love for God through inspiring poems and stories centered on nature, love, and faith, aiming to bless and bring joy to readers.

- Explore Heartfelt Poems and Stories for Inspiration: Poems and stories to warm your heart.

- Heartfelt Tales of My Beloved Pets: The author shares stories of various animals that have impacted their life, encouraging love for pets and providing comforting Bible verses for grieving pet owners.

Children bible study

- Bible Studies by Bell [Some nice little Bible studies for kids.]

Children recipes

Children fun facts

- Discover Amazing Facts about the World {Having all kind of facts about many different topics.}

- Science Facts Pages for Kids

- Explore Country Facts Organized by Continent

- Discovering Patterns in the 12 Times Tables

Pictures

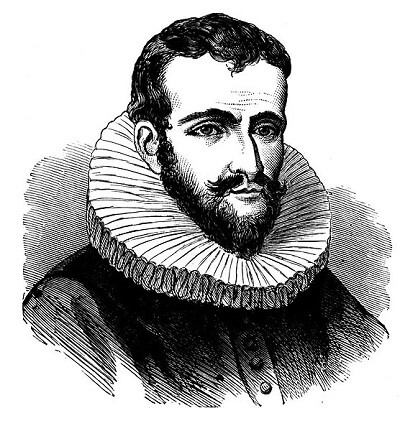

‘Engraving of Juan Ponce de León’

‘Engraving of Juan Ponce de León’

‘Portrait of Governor John Winthrop’ by Anthony van Dyck

‘Portrait of Governor John Winthrop’ by Anthony van Dyck