The Starving Time, and What Followed

The Starving Time, and What Followed

When Captain John Smith went back to England, in 1609, there were nearly five hundred settlers in Virginia. But the settlers soon got into trouble with the American Indians, who lay in the woods and killed every one that ventured out. There was no longer any chance to buy corn, and the food was soon exhausted. The starving people ate the hogs, the dogs, and the horses, even to their skins. Then they ate rats, mice, snakes, toadstools, and whatever they could get that might stop their hunger. One deceased American Indian was eaten, and, as their hunger grew more extreme, they were forced to consume their own dead. Starving men wandered off into the woods and died there; their companions, finding them, devoured them as hungry wild beasts might have done. This was always afterward remembered as “the starving time.”

Along with the people who came at the close of John Smith’s time, there had been sent another shipload of people, with Sir Thomas Gates, a new governor for the colony. This vessel had been shipwrecked, but Gates and his people had got ashore on the Bermuda Islands. These islands had no inhabitants at that time. Here these shipwrecked people lived well on wild hogs. When spring came, they built two little vessels of the cedar trees which grew on the island. These they rigged with sails taken from their wrecked ships, and getting their people aboard they made their way to Jamestown.

When they got there, they found alive but sixty of the four hundred and ninety people left in Virginia in the autumn before, and these sixty would all have died had Gates been ten days later in coming. The food that Gates brought would barely last them sixteen days. So he put the Jamestown people aboard his little cedar ships, intending to sail to Newfoundland, in hope of there falling in with some English fishing-vessels. He set sail down the river, leaving not one English settler on the whole continent of America.

Just before Gates and his people got out of the James River, they met a long boat rowing up toward them. Lord De la Warr had been appointed governor of Virginia, and sent out from England. From some men at the mouth of the river he had learned that Gates and all the people were coming down. He sent his long boat to turn them back again. On a Sunday morning De la Warr landed in Jamestown and knelt on the ground a while in prayer. Then he went to the little church, where he took possession of the government, and rebuked the people for the idleness that had brought them into such suffering. ‘Pocahontas’ After Simon van de Passe

‘Pocahontas’ After Simon van de Passe

During this summer of 1610, a hundred and fifty of the settlers died, and Lord De la Warr, finding himself very ill, left the colony. The next year Sir Thomas Dale took charge, and Virginia was under his government and that of Sir Thomas Gates for five years afterward.

Dale was a soldier, and ruled with extreme severity. He forced the idle settlers to labor, he drove away some of the American Indians, settled some new towns, and he built fortifications. But he was so harsh that the people hated him. He punished men by flogging and by setting them to work in irons for years. Those who rebelled or ran away were put to death in cruel ways; some were burned alive, others were broken on the wheel, and one man, for merely stealing food, was starved to death.

Powhatan, the head chief of the neighboring tribes, gave the colony a great deal of trouble during the first part of Dale’s time. His daughter, Pocahontas, who, as a child, had often played with the boys within the palisades of Jamestown, and had shown herself friendly to Captain Smith and others in their trips among the American Indians, was now a woman grown. While she was visiting a chief named Japazaws, an English captain named Argall hired that chief with a copper kettle to betray her into his hands. Argall took her a captive to Jamestown. Here a settler by the name of John Rolfe married her, after she had received Christian baptism. This marriage brought about a peace between Powhatan and the English settlers in Virginia.

When Dale went back to England in 1616, he took with him some of the American Indians. Pocahontas, who was now called “the Lady Rebecca,” and her husband went to England with Dale. Pocahontas was called a “princess” in England, and received much attention. But she died when about to start back to the colony, leaving a little son.

The same John Rolfe who married Pocahontas was the first Englishman to raise tobacco in Virginia. This he did in 1612. Tobacco brought a large price in that day, and, as it furnished a means by which people in Virginia could make a living, it helped to make the colony successful. But in 1616 there were only three hundred and fifty English people in all North America.

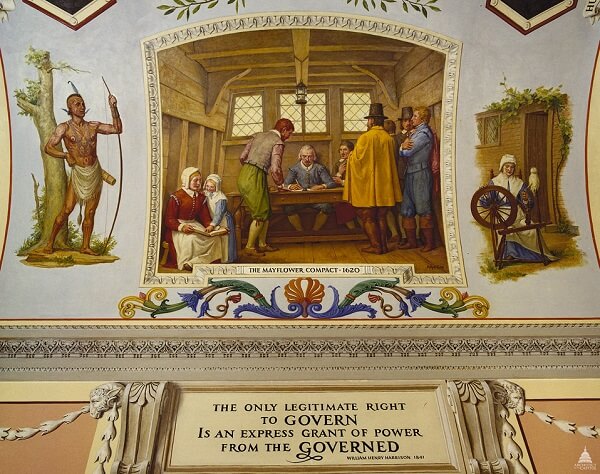

‘The Mayflower Compact, 1620’ by the Architect of the Capitol

‘The Mayflower Compact, 1620’ by the Architect of the Capitol Replica Ship Susan Constant (In Front of Navy Vessel)

Replica Ship Susan Constant (In Front of Navy Vessel)

Captain John Smith

Captain John Smith

Queen Elizabeth I of England

Queen Elizabeth I of England Tobacco Field in South Carolina

Tobacco Field in South Carolina