The Golden Touch part 2

The Golden Touch Continued

VI.

Midas, meanwhile, had poured out a cup of coffee; and, as a matter of course, the coffeepot, whatever metal it may have been when he took it up, was gold when he set it down. He thought to himself that it was rather an extravagant style of splendor, in a king of his simple habits, to breakfast off a service of gold, and began to be puzzled with the difficulty of keeping his treasures safe. The cupboard and the kitchen would no longer be a secure place of deposit for articles so valuable as golden bowls and golden coffeepots.

Amid these thoughts, he lifted a spoonful of coffee to his lips, and, sipping it, was astonished to perceive that the instant his lips touched the liquid it became molten gold, and the next moment, hardened into a lump!

“Ha!” exclaimed Midas, rather aghast.

“What is the matter, father?” asked little Marygold, gazing at him, with the tears still standing in her eyes.

“Nothing, child, nothing!” said Midas. “Take your milk before it gets quite cold.”

He took one of the nice little trouts on his plate, and touched its tail with his finger. To his horror, it was immediately changed from a brook trout into a gold fish, and looked as if it had been very cunningly made by the nicest goldsmith in the world. Its little bones were now golden wires; its fins and tail were thin plates of gold; and there were the marks of the fork in it, and all the delicate, frothy appearance of a nicely fried fish, exactly imitated in metal.

“I don’t quite see,” thought he to himself, “how I am to get any breakfast!”

He took one of the smoking-hot cakes, and had scarcely broken it, when, to his cruel mortification, though a moment before, it had been of the whitest wheat, it assumed the yellow hue of Indian meal. Its solidity and increased weight made him too bitterly sensible that it was gold. Almost in despair, he helped himself to a boiled egg, which immediately underwent a change similar to that of the trout and the cake.

“Well, this is terrible!” thought he, leaning back in his chair, and looking quite enviously at little Marygold, who was now eating her bread and milk with great satisfaction. “Such a costly breakfast before me, and nothing that can be eaten!”

VII.

Hoping that, by dint of great dispatch, he might avoid what he now felt to be a considerable inconvenience, King Midas next snatched a hot potato, and attempted to cram it into his mouth, and swallow it in a hurry. But the Golden Touch was too nimble for him. He found his mouth full, not of mealy potato, but of solid metal, which so burnt his tongue that he roared aloud, and, jumping up from the table, began to dance and stamp about the room, both with pain and affright.

“Father, dear father!” cried little Marygold, who was a very affectionate child, “pray what is the matter? Have you burnt your mouth?”

“Ah, dear child,” groaned Midas, dolefully, “I don’t know what is to become of your poor father!”

And, truly, did you ever hear of such a pitiable case, in all your lives? Here was literally the richest breakfast that could be set before a king, and its very richness made it absolutely good for nothing. The poorest laborer, sitting down to his crust of bread and cup of water, was far better off than King Midas, whose delicate food was really worth its weight in gold.

And what was to be done? Already, at breakfast, Midas was excessively hungry. Would he be less so by dinner time? And how ravenous would be his appetite for supper, which must undoubtedly consist of the same sort of indigestible dishes as those now before him! How many days, think you, would he survive a continuance of this rich fare?

These reflections so troubled wise King Midas, that he began to doubt whether, after all, riches are the one desirable thing in the world, or even the most desirable. But this was only a passing thought. So fascinated was Midas with the glitter of the yellow metal, that he would still have refused to give up the Golden Touch for so paltry a consideration as a breakfast. Just imagine what a price for one meal’s victuals! It would have been the same as paying millions and millions of money for some fried trout, an egg, a potato, a hot cake, and a cup of coffee!

“It would be much too dear,” thought Midas.

Nevertheless, so great was his hunger, and the perplexity of his situation, that he again groaned aloud, and very grievously too. Our pretty Marygold could endure it no longer. She sat a moment gazing at her father, and trying, with all the might of her little wits, to find out what was the matter with him. Then, with a sweet and sorrowful impulse to comfort him, she started from her chair, and, running to Midas, threw her arms affectionately about his knees. He bent down and kissed her. He felt that his little daughter’s love was worth a thousand times more than he had gained by the Golden Touch.

“My precious, precious Marygold!” cried he.

But Marygold made no answer.

VIII.

Alas, what had King Midas done? How fatal was the gift which the stranger had bestowed! The moment the lips of Midas touched Marygold’s forehead, a change had taken place. Her sweet, rosy face, so full of affection as it had been, assumed a glittering yellow color, with yellow tear-drops congealing on her cheeks. Her beautiful brown ringlets took the same tint. Her soft and tender little form grew hard and inflexible within her father’s encircling arms. O terrible misfortune! The victim of his insatiable desire for wealth, little Marygold was a human child no longer, but a golden statue!

Yes, there she was, with the questioning look of love, grief, and pity, hardened into her face. It was the prettiest and most woeful sight that ever mortal saw. All the features and tokens of Marygold were there; even the beloved little dimple remained in her golden chin. But, the more perfect was the resemblance, the greater was the father’s agony at beholding this golden image, which was all that was left him of a daughter.

It had been a favorite phrase of Midas, whenever he felt particularly fond of the child, to say that she was worth her weight in gold. And now the phrase had become literally true. And, now, at last, when it was too late, he felt how infinitely a warm and tender heart, that loved him, exceeded in value all the wealth that could be piled up betwixt the earth and sky!

It would be too sad a story, if I were to tell you how Midas, in the fullness of all his gratified desires, began to wring his hands and bemoan himself; and how he could neither bear to look at Marygold, nor yet to look away from her. Except when his eyes were fixed on the image, he could not possibly believe that she was changed to gold. But, stealing another glance, there was the precious little figure, with a yellow tear-drop on its yellow cheek, and a look so piteous and tender, that it seemed as if that very expression must needs soften the gold, and make it flesh again. This, however, could not be. So Midas had only to wring his hands, and to wish that he were the poorest man in the wide world, if the loss of all his wealth might bring back the faintest rose-color to his dear child’s face.

IX.

While he was in this tumult of despair, he suddenly beheld a stranger, standing near the door. Midas bent down his head, without speaking; for he recognized the same figure which had appeared to him the day before in the treasure room, and had bestowed on him this disastrous power of the Golden Touch. The stranger’s countenance still wore a smile, which seemed to shed a yellow luster all about the room, and gleamed on little Marygold’s image, and on the other objects that had been transmuted by the touch of Midas.

“Well, friend Midas,” said the stranger, “pray, how do you succeed with the Golden Touch?”

Midas shook his head.

“I am very miserable,” said he.

“Very miserable! indeed!” exclaimed the stranger; “and how happens that? Have I not faithfully kept my promise with you? Have you not everything that your heart desired?”

“Gold is not everything,” answered Midas. “And I have lost all that my heart really cared for.”

“Ah! So you have made a discovery, since yesterday?” observed the stranger. “Let us see, then. Which of these two things do you think is really worth the most,—the gift of the Golden Touch, or one cup of clear cold water?”

“O blessed water!” exclaimed Midas. “It will never moisten my parched throat again!”

“The Golden Touch,” continued the stranger, “or a crust of bread?”

“A piece of bread,” answered Midas, “is worth all the gold on earth!”

“The Golden Touch,” asked the stranger, “or your own little Marygold, warm, soft, and loving, as she was an hour ago?”

“O my child, my dear child!” cried poor King Midas, wringing his hands. “I would not have given that one small dimple in her chin for the power of changing this whole big earth into a solid lump of gold!”

“You are wiser than you were, King Midas?” said the stranger, looking seriously at him. “Your own heart, I perceive, has not been entirely changed from flesh to gold. Were it so, your case would indeed be desperate. But you appear to be still capable of understanding that the commonest things, such as lie within everybody’s grasp, are more valuable than the riches which so many mortals sigh and struggle after. Tell me, now, do you sincerely desire to rid yourself of this Golden Touch?”

“It is hateful to me!” replied Midas.

A fly settled on his nose, but immediately fell to the floor; for it, too, had become gold. Midas shuddered.

“Go, then,” said the stranger, “and plunge into the river that glides past the bottom of your garden. Take likewise a vase of the same water, and sprinkle it over any object that you may desire to change back again from gold into its former substance. If you do this in earnestness and sincerity, it may possibly repair the mischief which your avarice has occasioned.”

King Midas bowed low; and when he lifted his head, the lustrous stranger had vanished.

X.

You will easily believe that Midas lost no time in snatching up a great earthen pitcher (but, alas me! it was no longer earthen after he touched it), and in hastening to the riverside. As he ran along, and forced his way through the shrubbery, it was positively marvelous to see how the foliage turned yellow behind him, as if the autumn had been there, and nowhere else. On reaching the river’s brink, he plunged headlong in, without waiting so much as to pull off his shoes.

“Poof! poof! poof!” gasped King Midas, as his head emerged out of the water. “Well; this is really a refreshing bath, and I think it must have quite washed away the Golden Touch. And now for filling my pitcher!”

As he dipped the pitcher into the water, it gladdened his very heart to see it change from gold into the same good, honest, earthen vessel which it had been before he touched it. He was conscious, also, of a change within himself. A cold, hard, and heavy weight seemed to have gone out of his bosom. No doubt his heart had been gradually losing its human substance, and been changing into insensible metal, but had now been softened back again into flesh. Perceiving a violet, that grew on the bank of the river, Midas touched it with his finger, and was overjoyed to find that the delicate flower retained its purple hue, instead of undergoing a yellow blight. The curse of the Golden Touch had, therefore, really been removed from him.

XI.

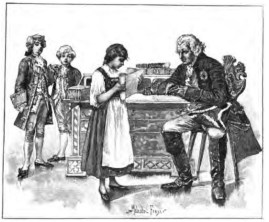

King Midas hastened back to the palace; and, I suppose, the servants knew not what to make of it when they saw their royal master so carefully bringing home an earthen pitcher of water. But that water, which was to undo all the mischief that his folly had wrought, was more precious to Midas than an ocean of molten gold could have been. The first thing he did, as you need hardly be told, was to sprinkle it by handfuls over the golden figure of little Marygold.

No sooner did it fall on her than you would have laughed to see how the rosy color came back to the dear child’s cheek!—and how astonished she was to find herself dripping wet, and her father still throwing more water over her!

“Pray do not, dear father!” cried she. “See how you have wet my nice frock, which I put on only this morning!”

For Marygold did not know that she had been a little golden statue; nor could she remember anything that had happened since the moment when she ran with outstretched arms to comfort her father.

Her father did not think it necessary to tell his beloved child how very foolish he had been, but contented himself with showing how much wiser he had now grown. For this purpose, he led little Marygold into the garden, where he sprinkled all the remainder of the water over the rosebushes, and with such good effect that above five thousand roses recovered their beautiful bloom. There were two circumstances, however, which, as long as he lived, used to remind King Midas of the Golden Touch. One was, that the sands of the river in which he had bathed, sparkled like gold; the other, that little Marygold’s hair had now a golden tinge, which he had never observed in it before she had been changed by the effect of his kiss. This change of hue was really an improvement, and made Marygold’s hair richer than in her babyhood.

When King Midas had grown quite an old man, and used to take Marygold’s children on his knee, he was fond of telling them this marvelous story. And then would he stroke their glossy ringlets, and tell them that their hair, likewise, had a rich shade of gold, which they had inherited from their mother.

“And, to tell you the truth, my precious little folks,” said King Midas, “ever since that morning, I have hated the very sight of all other gold, save this!”

—From “A Wonder Book for Boys and Girls.”