Franklin, the Printer

When Ben Franklin left his brother, he tried in vain to get a place in one of the other printing offices in Boston. But James Franklin had sent word to the other printers not to take Benjamin into their employ. There was no other town nearer than New York large enough to support a printing office. Franklin, who was now but seventeen years old, sold some of his books, and secretly got aboard a sloop ready to sail to New York. In New York he could find no work but was recommended to try in Philadelphia.

The modes of travel in that time were very rough. The easiest way of getting from Boston to New York was by sailing vessels. To get to Philadelphia, Franklin had first to take a sailboat to Amboy, in New Jersey. On the way, a squall of wind tore the sails and drove the boat to anchor near the Long Island shore, where our runaway boy lay all night in the little hold of the boat, with the waves beating over the deck and the water leaking down on him. When at last he landed at Amboy, he had been thirty hours without anything to eat or any water to drink.

Having but little money in his pocket, he had to walk from Amboy to Burlington; and when, soaked by rain, he stopped at an inn, he cut such a figure that the people came near arresting him for a runaway bond servant, of whom there were many in that time. He thought he might better have stayed at home.

This tired and mud-spattered young fellow got a chance to go from Burlington to Philadelphia in a rowboat by taking his turn at the oars. There were no street lamps in the town of Philadelphia, and the men in the boat passed the town without knowing it. Like forlorn tramps, they landed and made a fire of some fence rails.

When they got back to Philadelphia in the morning, Franklin — who was to become in time the most famous man in that town — walked up the street in his working clothes, which were badly soiled by his rough journey. His spare stockings and shirt were stuffed into his pockets. He bought three large rolls at a baker’s shop. One of these he carried under each arm; the other he munched as he walked.

As he passed along the street, a girl named Deborah Read stood in the door of her lather’s house and laughed at the funny sight of a young fellow with bulging pockets and a roll under each arm. Years afterward this same Deborah was married to Franklin.

Franklin got a place to work with a printer named Keimer. He was now only a poor printer-boy, in leather breeches such as workingmen wore at that time. But, though he looked poor, he was already different from most of the boys in Philadelphia. He was a lover of good books. The child who has learned to read the best books will be an educated citizen, with or without schools. The great difference between people is shown in the way they spend their leisure time. Franklin, when not studying, spent his evenings with a few young people who were also fond of books. Here is the sort of young person that will come to something.

I suppose people began to notice and talk about this studious young workman. One day Keimer, the printer for whom Franklin was at work, saw coming toward his office, Sir William Keith, the governor of the province of Pennsylvania, and another gentleman, both finely dressed after the fashion of the time, in powdered periwigs and silver knee buckles. Keimer was delighted to have such visitors, and he ran down to meet the men. But imagine his disappointment when the governor asked to see Franklin and led away the young printer in leather breeches to talk with him in the tavern.

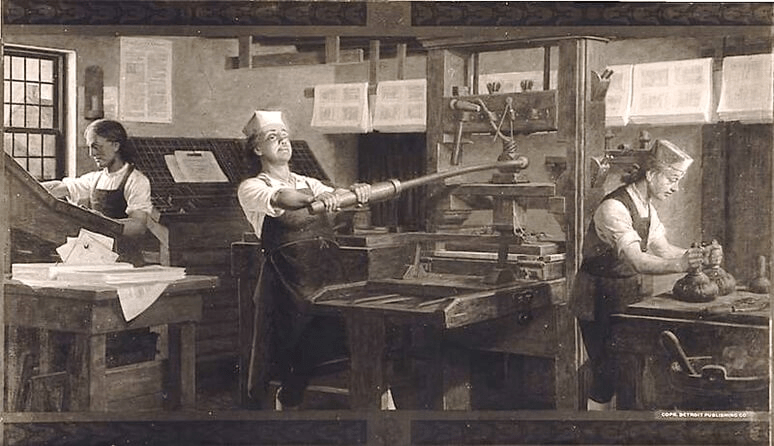

The governor wanted Franklin to set up a printing office of his own, because both Keimer and the other masterprinter in Philadelphia were poor workmen. But Franklin had no money, and it took a great deal to buy a printing press and types in that day. Franklin told the governor that he did not believe his father would help him to buy an outfit. But the governor wrote a letter himself to Franklin’s father, asking him to start Benjamin in business.

So Franklin went back to Boston in a better plight than that in which he had left. He had on a brand new suit of clothes, he carried a watch, and he had some silver in his pockets. His father and mother were glad to see him once more, but his father told him he was too young to start in business for himself.

Franklin returned to Philadelphia. Governor Keith, who was one of those gentlemen that make many promising speeches, now offered to start Franklin himself. He wanted him to go to London to buy the printing press. He promised to give the young man letters to people in London, and one that would get him the money to buy the press.

But, somehow, every time that Franklin called on the governor for the letters he was told to call again. At last, Franklin went on shipboard, thinking the governor had sent the letters in the ship’s letterbag. Before the ship got to England the bag was opened, and no letters for Franklin were found. A gentleman now told Franklin that Keith made a great many such promises, but he never kept them. Fine clothes do not make a fine gentleman.

So Franklin was left in London without money or friends. But he got work as a printer, and learned some things about the business that he could not learn in America. The English printers drank a great deal of beer. They laughed at Franklin because he did not use beer, and they called him the “Water American.” But Franklin wasn’t a fellow to be afraid of ridicule. The English printers told Franklin that water would make him weak, but they were surprised to find him able to lift more than any of them. Franklin was also a strong swimmer. In London, Franklin kept up his reading. He paid a man who kept a secondhand bookstore for permission to read his books.

Franklin came back to Philadelphia as clerk for a merchant, but the merchant soon died, and Franklin went to work again for his old master, Keimer. He was very useful, for he could make ink and cast type when they were needed, and he also engraved some designs on type metal. Keimer once fell out with Franklin and discharged him, but he begged him to come back when there was some paper money to be printed, which Keimer could not print without Franklin’s help in making the engravings.