The Coming of the Puritans

Before the Pilgrims had become comfortably settled in their new home, other English people came to various parts of the New England coast to the northward of Plymouth. About 1623, a few scattering immigrants, mostly fishermen, traders with the American Indians, and timber-cutters, began to settle here and there along the sea about Massachusetts Bay, and later came to the colonies of New Hampshire and Maine.

We have seen in the preceding chapter that the Pilgrims belonged to that party which had separated itself from the Church of England, and so got the name of Separatists. But there were also a great many people who did not like the ceremonies of the established church, but who would not leave it. These were called Puritans, because they sought to purify the Church from what they thought to be wrong. They formed a large part of the English people, and at a later time, under Oliver Cromwell, they got control of England. But at the time of the settlement of New England the party opposed to the Puritans was in power, and the Puritans were persecuted. The little colony of Plymouth, which had now got through its sufferings, showed them a way out of their troubles. Many of the Puritans began to think of emigration.

In 1628, when Plymouth had been settled almost eight years, the Massachusetts Company was formed. This was a company like the Virginia Company that had governed Virginia at first. The Massachusetts Company was controlled by Puritans, and proposed to make settlements within the territory granted to it in New England. The first party sent out by this company settled at Salem in 1628. Others were sent the next year.

But in 1630 a new and bold move was made. The Massachusetts Company resolved to change the place of holding its meetings from London to its new colony in America. This would give the people in the colony, as members of the company, a right to govern themselves. When this proposed change became known in England, many of the Puritans desired to go to America. ‘Portrait of Governor John Winthrop’ by Anthony van Dyck

‘Portrait of Governor John Winthrop’ by Anthony van Dyck

John Winthrop, the new governor, set sail for Massachusetts in 1630, with the charter and about a thousand people, Winthrop and a part of his company settled at Boston, and that became the capital of the colony. No colony was settled more rapidly than Massachusetts. Twenty thousand people came between 1630 and 1640, though the colony was troubled for a while by bitter disputes among its people about matters of religion and by a war with the Pequot Indians.

Some of the Puritans in Massachusetts were dissatisfied with their lands. In 1635 and 1636 these people crossed Connecticut through the unbroken woods to the Connecticut River, and settled the towns of Windsor, Wethersfield, and Hartford, though there were already trading posts on the Connecticut River. This was the beginning of the Colony of Connecticut. Another colony was planted in 1638 in the region about New Haven. It was made up of Puritans under the lead of the Rev. John Davenport. In 1665 New Haven Colony was united with Connecticut.

In 1636 Roger Williams, a minister at Salem, in Massachusetts, was banished from that colony on account of his peculiar views on several subjects, religious and political. One of these was the doctrine that every man had a right to worship God without interference by the government. Williams went to the head of Narragansett Bay and established a settlement on the principle of entire religious liberty. The disputes in Massachusetts resulted in other settlements of banished people on Narragansett Bay, which were all at length united in one colony, from which came the present State of Rhode Island.

The first settlement of New Hampshire was made at Little Harbor, near Portsmouth, in 1623. The population of New Hampshire was increased by those who left the Massachusetts Colony on account of the religious disputes and persecutions there. Other settlers came from England. But there was much confusion and dispute about land-titles and about government, in consequence of which the colony was settled slowly. New Hampshire was several times joined to Massachusetts, but it was finally separated from it in 1741.

As early as 1607, about the time Virginia was settled, a colony was planted in Maine; but this attempt failed. The first permanent settlement in Maine was made at Pemaquid in 1625. Maine submitted to Massachusetts in 1652, but it afterward suffered disorders from conflicting governments until it was at length annexed to Massachusetts by the charter given to that colony in 1692. It remained a part of Massachusetts until it was admitted to the Union as a separate State, in 1820.

The New England colonies were governed under charters, which left them, in general, free from interference from England. Plymouth, Massachusetts, Connecticut, New Haven, and Rhode Island were the only colonies on the continent that had the privilege of choosing their own governors. In 1684 the first Massachusetts charter was taken away, and after that the governors of Massachusetts were appointed by the king, but under a new charter given in 1692 the colony enjoyed the greater part of its old liberties.

JOHN WINTHROP

John Winthrop, the principal founder of Massachusetts, was born in 1588. He was chosen Governor of the Massachusetts Company, and brought the charter and all the machinery of the government with him to America in 1630. He was almost continually governor until he died in 1649. He was a man of great wisdom. When another of the leading men in the colony wrote him an angry letter, he sent it back, saying that “he was not willing to keep such a provocation to ill-feeling by him.” The writer of the letter answered, “Your overcoming yourself has overcome me.” When the colony had little food, and Winthrop’s last bread was in the oven, he divided the small remainder of his flour among the poor. That very day a shipload of provisions came. He dressed plainly, drank little but water, and labored with his hands among his servants. He counted it the great comfort of his life that he had a “loving and dutiful son.” This son was also named John. He was a man of excellent virtues, and was the first Governor of Connecticut.

‘Pocahontas’ After Simon van de Passe

‘Pocahontas’ After Simon van de Passe

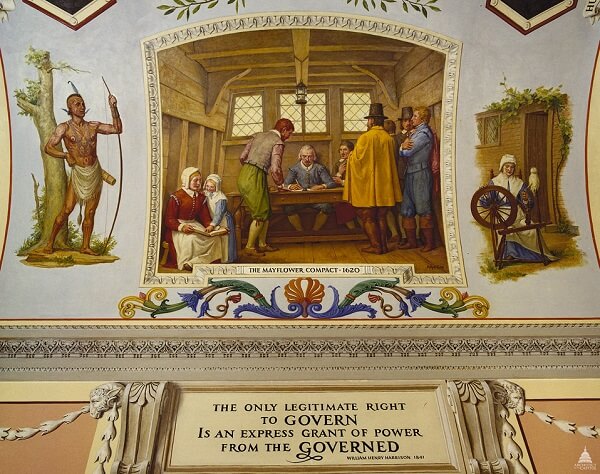

‘The Mayflower Compact, 1620’ by the Architect of the Capitol

‘The Mayflower Compact, 1620’ by the Architect of the Capitol Replica Ship Susan Constant (In Front of Navy Vessel)

Replica Ship Susan Constant (In Front of Navy Vessel)

Captain John Smith

Captain John Smith

Queen Elizabeth I of England

Queen Elizabeth I of England Tobacco Field in South Carolina

Tobacco Field in South Carolina