Posts tagged ‘Children’s Literature’

It is said that the effect of eating too much lettuce is “soporific.” I have never felt sleepy after eating lettuces; but then I am not a rabbit. They certainly had a very soporific effect upon the Flopsy Bunnies!

Heidi Chapter 15

Preparations For a Journey

The kind doctor who had sent Heidi home to her beloved mountains was approaching the Sesemann residence on a sunny day in September. Everything about him was bright and cheerful, but the doctor did not even raise his eyes from the pavement to the blue sky above. His face was sad and his hair had turned very gray since spring. A few months ago the doctor had lost his only daughter, who had lived with him since his wife’s early death. The blooming girl had been his only joy, and since she had gone from him the ever-cheerful doctor was bowed down with grief.

When Sebastian opened the door to the physician he bowed very low, for the doctor made friends wherever he went.

“I am glad you have come doctor,” Mr. Sesemann called to his friend as he entered. “Please let us talk over this trip to Switzerland again. Do you still give the same advice, now that Clara is so much better?”

“What must I think of you, Sesemann?” replied the doctor, sitting down. “I wish your mother was here. Everything is clear to her and things go smoothly then. This is the third time to-day that you have called me, and always for the same thing!”

“It is true, it must make you impatient,” said Mr. Sesemann. Laying his hand on his friend’s shoulder, he continued: “I cannot say how hard it is for me to refuse Clara this trip. Haven’t I promised it to her and hasn’t she looked forward to it for months? She has borne all her suffering so patiently, just because she had hoped to be able to visit her little friend on the Alp. I hate to rob her of this pleasure. The poor child has so many trials and so little change.”

“But, Sesemann, you must do it,” was the doctor’s answer. When his friend remained silent, he continued: “Just think what a hard summer Clara has had! She never was more ill and we could not attempt this journey without risking the worst consequences. Remember, we are in September now, and though the weather may still be fine on the Alp, it is sure to be very cool. The days are getting short, and she could only spend a few hours up there, if she had to return for the night. It would take several hours to have her carried up from Ragatz. You see yourself how impossible it is! I shall come in with you, though, to talk to Clara, and you’ll find her sensible. I’ll tell you of my plan for next May. First she can go to Ragatz to take the baths. When it gets warm on the mountain, she can be carried up from time to time. She’ll be stronger then and much more able to enjoy those excursions than she is now. If we hope for an improvement in her condition, we must be extremely cautious and careful, remember that!”

Mr. Sesemann, who had been listening with the utmost submission, now said anxiously: “Doctor, please tell me honestly if you still have hope left for any change?”

With shrugging shoulders the doctor replied: “Not very much. But think of me, Sesemann! Have you not a child, who loves you and always welcomes you? You don’t have to come back to a lonely house and sit down alone at your table. Your child is well taken care of, and if she has many privations, she also has many advantages. Sesemann, you do not need to be pitied! Just think of my lonely home!”

Mr. Sesemann had gotten up and was walking round the room, as he always did when something occupied his thoughts. Suddenly he stood before his friend and said: “Doctor, I have an idea. I cannot see you sad any longer. You must get away. You shall undertake this trip and visit Heidi in our stead.”

The doctor had been surprised by this proposal, and tried to object. But Mr. Sesemann was so full of his new project that he pulled his friend with him into his daughter’s room, not leaving him time for any remonstrances. Clara loved the doctor, who had always tried to cheer her up on his visits by bright and funny tales. She was sorry for the change that had come over him and would have given much to see him happy again. When he had shaken hands with her, both men pulled up their chairs to Clara’s bedside. Mr. Sesemann began to speak of their journey and how sorry he was to give it up. Then he quickly began to talk of his new plan.

Clara’s eyes had filled with tears. But she knew that her father did not like to see her cry, and besides she was sure that her papa would only forbid her this pleasure because it was absolutely necessary to do so.

So she bravely fought her tears, and caressing the doctor’s hand, said:

“Oh please, doctor, do go to Heidi; then you can tell me all about her, and can describe her grandfather to me, and Peter, with his goats,—I seem to know them all so well. Then you can take all the things to her that I had planned to take myself. Oh, please doctor, go, and then I’ll be good and take as much cod-liver oil as ever you want me to.”

Who can tell if this promise decided the doctor? At any rate he answered with a smile: “Then I surely must go, Clara, for you will get fat and strong, as we both want to see you. Have you settled yet when I must go?”

“Oh, you had better go tomorrow morning, doctor,” Clara urged.

“She is right,” the father assented; “the sun is shining and you must not lose any more glorious days on the Alp.”

The doctor had to laugh. “Why don’t you chide me for being here still? I shall go as quickly as I can, Sesemann.”

Clara gave many messages to him for Heidi. She also told him to be sure to observe everything closely, so that he would be able to tell her all about it when he came back. The things for Heidi were to be sent to him later, for Miss Rottenmeier, who had to pack them, was out on one of her lengthy wanderings about town.

The doctor promised to comply with all Clara’s wishes and to start the following day.

Clara rang for the maid and said to her, when she arrived: “Please, Tinette, pack a lot of fresh, soft coffee-cake in this box.” A box had been ready for this purpose many days. When the maid was leaving the room she murmured: “That’s a silly bother!”

Sebastian, who had happened to overhear some remarks, asked the physician when he was leaving to take his regards to the little Miss, as he called Heidi.

With a promise to deliver this message the doctor was just hastening out, when he encountered an obstacle. Miss Rottenmeier, who had been obliged to return from her walk on account of the strong wind, was just coming in. She wore a large cape, which the wind was blowing about her like two full sails. Both had retreated politely to give way to each other. Suddenly the wind seemed to carry the housekeeper straight towards the doctor, who had barely time to avoid her. This little incident, which had ruffled Miss Rottenmeier’s temper very much, gave the doctor occasion to soothe her, as she liked to be soothed by this man, whom she respected more than anybody in the world. Telling her of his intended visit, he entreated her to pack the things for Heidi as only she knew how.

Clara had expected some resistance from Miss Rottenmeier about the packing of her presents. What was her surprise when this lady showed herself most obliging, and immediately, on being told, brought together all the articles! First came a heavy coat for Heidi, with a hood, which Clara meant her to use on visits to the grandmother in the winter. Then came a thick warm shawl and a large box with coffee-cake for the grandmother. An enormous sausage for Peter’s mother followed, and a little sack of tobacco for the grandfather. At last a lot of mysterious little parcels and boxes were packed, things that Clara had gathered together for Heidi. When the tidy pack lay ready on the ground, Clara’s heart filled with pleasure at the thought of her little friend’s delight.

Sebastian now entered, and putting the pack on his shoulder, carried it to the doctor’s house without delay.

Swiss Family Robinson Chapter 48

Chapter 48

A gentle wind swelled our sails, and the current carried us rapidly into the open sea. I then seated myself at the helm, and employed the little knowledge I had gained during our voyage from Europe in directing our bark, so that we might avoid the rocks and coral banks that surrounded our island. My two oldest sons, overcome with fatigue, had no sooner seated themselves on a bench, than they fell into a profound sleep, notwithstanding their sorrows. Jack held out the best; his love of the sea kept him awake, and I surrendered the helm to him till I took a momentary slumber, my head resting against the stern. A happy dream placed me in the midst of my family in our dear island; but a shout from Ernest awoke me, he was calling on Jack to leave the helm, as he was contriving to run the vessel among the breakers on the coast. I seized the helm, and soon set all right, determined not to trust my giddy son again.

Jack, of all my sons, was the one who evinced most taste for the sea; but being so young when we made our voyage, his knowledge of nautical affairs was very scanty. My elder sons had learnt more. Ernest, who had a great thirst for knowledge of every kind, had questioned the pilot on all he had seen him do. He had learned a great deal in theory, but of practical knowledge he had none. The mechanical genius of Fritz had drawn conclusions from what he saw; this would have induced me to place much trust in him in case of that danger which I prayed Heaven might be averted. What a situation was mine for a father! Wandering through unknown and dangerous seas with my three sons, my only hope, in search of a fourth, and of my beloved helpmate; utterly ignorant which way we should direct our course, or where to find a trace of those we sought. How often do we allay the happiness granted us below by vain wishes! I had at one time regretted that we had no means of leaving our island; now we had left it, and our sole wish was to recover those we had lost, to bring them back to it, and never to leave it more. I sometimes regretted that I had led my sons into this danger. I might have ventured alone; but I reflected that I could not have left them, for Fritz had said, “If the natives had carried off the pinnace, I would have swum from isle to isle till I had found them.” My boys all endeavoured to encourage and console me. Fritz placed himself at the rudder, observing that the pinnace was new and well built, and likely to resist a tempest. Ernest stood on the deck silently watching the stars, only breaking his silence by telling me he should be able by them to supply the want of the compass, and point out how we should direct our course. Jack climbed dexterously up the mast to let me see his skill; we called him the cabin-boy, Fritz was the pilot, Ernest the astronomer, and I was the captain and commander of the expedition. Daybreak showed us we had passed far from our island, which now only appeared a dark speck. I, as well as Fritz and Jack, was of opinion that it would be advisable to go round it, and try our fortune on the opposite coast; but Ernest, who had not forgotten his telescope, was certain he saw land in a direction he pointed out to us. We took the glass, and were soon convinced he was right. As day advanced, we saw the land plainly, and did not hesitate to sail towards it.

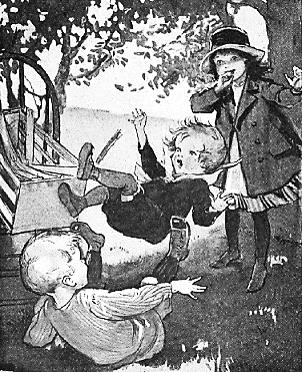

As this appeared the land nearest to our island, we supposed the natives might have conveyed their captives there. But more trials awaited us before we arrived there. It being necessary to shift the sail, in order to reach the coast in view, my poor cabin-boy, Jack, ran up the mast, holding by the ropes; but before he reached the sail, the rope which he held broke suddenly; he was precipitated into the sea, and disappeared in a moment; but he soon rose to the surface, trying to swim, and mingling his cries with ours. Fritz, who was the first to see the accident, was in the water almost as soon as Jack, and seizing him by the hair, swam with the other hand, calling on him to try and keep afloat, and hold by him. When I saw my two sons thus struggling with the waves, that were very strong from a land wind, I should, in my despair, have leaped in after them; but Ernest held me, and implored me to remain to assist in getting them into the pinnace. He had thrown ropes to them, and a bench which he had torn up with the strength of despair. Fritz had contrived to catch one of the ropes and fasten it round Jack, who still swam, but feebly, as if nearly exhausted. Fritz had been considered an excellent swimmer in Switzerland; he preserved all his presence of mind, calling to us to draw the rope gently, while he supported the poor boy, and pushed him towards the pinnace. At last I was able to reach and draw him up; and when I saw him extended, nearly lifeless, at the bottom of the pinnace, I fell down senseless beside him. How precious to us now was the composed mind of Ernest! In the midst of such a scene, he was calm and collected; promptly disengaging the rope from the body of Jack, he flung it back to Fritz, to help him in reaching the pinnace, attaching the other end firmly to the mast. This done, quicker than I can write it, he approached us, raised his brother so that he might relieve himself from the quantity of water he had swallowed; then turning to me, restored me to my senses by administering to me some drops of rum, and by saying, “Courage, father! you have saved Jack, and I will save Fritz. He has hold of the rope; he is swimming strongly; he is coming; he is here!”

He left me to assist his brother, who was soon in the vessel, and in my arms. Jack, perfectly recovered, joined him; and fervently did I thank God for granting me, in the midst of my trials, such a moment of happiness. We could not help fancying this happy preservation was an augury of our success in our anxious search, and that we should bring back the lost ones to our island.

“Oh, how terrified mamma would have been,” said Jack, “to see me sink! I thought I was going, like a stone, to the bottom of the sea; but I pushed out my arms and legs with all my strength, and up I rose.”

He as well as Fritz was quite wet. I had by chance brought some changes of clothes, which I made them put on, after giving each a little rum. They were so much fatigued, and I was so overcome by my agitation, that we were obliged to relinquish rowing, most unwillingly, as the skies threatened a storm. We gradually began to distinguish clearly the island we wished to approach; and the land-birds, which came to rest on our sails, gave us hopes that we should reach it before night; but, suddenly, such a thick fog arose, that it hid every object from us, even the sea itself, and we seemed to be sailing among the clouds. I thought it prudent to drop our anchor, as, fortunately, we had a tolerably strong one; but there appeared so little water, that I feared we were near the breakers, and I watched anxiously for the fog to dissipate, and permit us to see the coast. It finally changed into a heavy rain, which we could with difficulty protect ourselves from; there was, however, a half-deck to the pinnace, under which we crept, and sheltered ourselves. Here, crowded close together, we talked over the late accident. Fritz assured me he was never in any danger, and that he would plunge again into the sea that moment, if he had the least hope that it would lead him to find his mother and Francis. We all said the same; though Jack confessed that his friends, the waves, had not received his visit very politely, but had even beat him very rudely.

“But I would bear twice as much,” said he, “to see mamma and dear Francis again. Do you think, papa, that the natives could ever hurt them? Mamma is so good, and Francis is so pretty! and then, poor mamma is so lame yet; I hope they would pity her, and carry her.”

Alas! I could not hope as my boy did; I feared that they would force her to walk. I tried to conceal other horrible fears, that almost threw me into despair. I recalled all the cruelties of the cannibal nations, and shuddered to think that my Elizabeth and my darling child were perhaps in their ferocious hands. Prayer and confidence in God were the only means, not to console, but to support me, and teach me to endure my heavy affliction with resignation. I looked on my three sons, and endeavoured, for their sakes, to hope and submit. The darkness rapidly increased, till it became total; we concluded it was night. The rain having ceased, I went out to strike a light, as I wished to hang the lighted lantern to the mast, when Ernest, who was on deck, called out loudly, “Father! brothers! come! the sea is on fire!” And, indeed, as far as the eye could reach, the surface of the water appeared in flames; this light, of the most brilliant, fiery red, reached even to the vessel, and we were surrounded by it. It was a sight at once beautiful, and almost terrific. Jack seriously inquired, if there was not a volcano at the bottom of the sea; and I astonished him much by telling him, that this light was caused by a kind of marine animals, which in form resembled plants so much, that they were formerly considered such; but naturalists and modern voyagers have entirely destroyed this error, and furnished proofs that they are organized beings, having all the spontaneous movements peculiar to animals. They feel when they are touched, seek for food, seize and devour it; they are of various kinds and colours, and are known under the general name of zoophytes.

“And this which glitters in such beautiful colours on the sea, is called pyrosoma,” said Ernest. “See, here are some I have caught in my hat; you may see them move. How they change colour orange, green, blue, like the rainbow; and when you touch them, the flame appears still more brilliant; now they are pale yellow.”

They amused themselves some time with these bright and beautiful creatures, which appear to have but a half-life. They occupied a large space on the water, and their astonishing radiance, in the midst of the darkness of the atmosphere, had such a striking and magnificent effect, that for a few moments we were diverted from our own sad thoughts; but an observation from Jack soon recalled them.

“If Francis passed this way,” said he, “how he would be amused with these funny creatures, which look like fire, but do not burn; but I know he would be afraid to touch them; and how much afraid mamma would be, as she likes no animals she does not know. Ah! how glad I shall be to tell her all about our voyage, and my excursion into the sea, and how Fritz dragged me by the hair, and what they call these fiery fishes; tell me again, Ernest; py py ”

“Pyrosoma, Mr. Peron calls them,” said Ernest. “The description of them is very interesting in his voyage, which I have read to mamma; and as she would recollect it, she would not be afraid.”

“I pray to God,” replied I, “that she may have nothing more to fear than the pyrosoma, and that we may soon see them again, with her and Francis.”

We all said Amen; and, the day breaking, we decided to weigh the anchor, and endeavour to find a passage through the reefs to reach the island, which we now distinctly saw, and which seemed an uncultivated and rocky coast. I resumed my place at the helm, my sons took the oars, and we advanced cautiously, sounding every minute. What would have become of us if our pinnace had been injured! The sea was perfectly calm, and, after prayer to God, and a slight refreshment, we proceeded forward, looking carefully round for any canoe of the natives it might be, even our own; but, no! we were not fortunate enough to discover any trace of our beloved friends, nor any symptom of the isle being inhabited; however, as it was our only point of hope, we did not wish to abandon it. By dint of searching, we found a small bay, which reminded us of our own. It was formed by a river, broad and deep enough for our pinnace to enter. We rowed in; and having placed our vessel in a creek, where it appeared to be secure, we began to consider the means of exploring the whole island.

Heidi Chapter 14 Part 2

On Sunday When The Church Bells Ring continued…

“What do you think will happen now?” Heidi asked. “You think that the father is angry and will say: ‘Didn’t I tell you?’ But just listen: ‘And his father saw him and had compassion and ran and fell on his neck. And the son said: Father, I have sinned against Heaven and in Thy sight, and am no more worthy to be called Thy son. But the father said to his servants: Bring forth the best robe and put it on him; and put a ring on his hand and shoes on his feet; and bring hither the fatted calf and kill it; and let us eat and be merry: For this my son was dead and is alive again; he was lost, and is found.’ And they began to be merry.”

“Isn’t it a beautiful story, grandfather?” asked Heidi, when he sat silently beside her.

“Yes, Heidi, it is,” said the grandfather, but so seriously that Heidi quietly looked at the pictures. “Look how happy he is,” she said, pointing to it.

A few hours later, when Heidi was sleeping soundly, the old man climbed up the ladder. Placing a little lamp beside the sleeping child, he watched her a long, long time. Her little hands were folded and her rosy face looked confident and peaceful. The old man now folded his hands and said in a low voice, while big tears rolled down his cheeks: “Father, I have sinned against Heaven and Thee, and am no more worthy to be Thy son!”

The next morning found the uncle standing before the door, looking about him over valley and mountain. A few early bells sounded from below and the birds sang their morning anthems.

Re-entering the house, he called: “Heidi, get up! The sun is shining! Put on a pretty dress, for we are going to church!”

That was a new call, and Heidi obeyed quickly. When the child came downstairs in her smart little frock, she opened her eyes wide. “Oh, grandfather!” she exclaimed, “I have never seen you in your Sunday coat with the silver buttons. Oh, how fine you look!”

The old man, turning to the child, said with a smile: “You look nice, too; come now!” With Heidi’s hand in his they wandered down together. The nearer they came to the village, the louder and richer the bells resounded. “Oh grandfather, do you hear it? It seems like a big, high feast,” said Heidi.

When they entered the church, all the people were singing. Though they sat down on the last bench behind, the people had noticed their presence and whispered it from ear to ear. When the pastor began to preach, his words were a loud thanksgiving that moved all his hearers. After the service the old man and the child walked to the parsonage. The clergyman had opened the door and received them with friendly words. “I have come to ask your forgiveness for my harsh words,” said the uncle. “I want to follow your advice to spend the winter here among you. If the people look at me askance, I can’t expect any better. I am sure, Mr. Pastor, you will not do so.”

The pastor’s friendly eyes sparkled, and with many a kind word he commended the uncle for this change, and putting his hand on Heidi’s curly hair, ushered them out. Thus the people, who had been all talking together about this great event, could see that their clergyman shook hands with the old man. The door of the parsonage was hardly shut, when the whole assembly came forward with outstretched hands and friendly greetings. Great seemed to be their joy at the old man’s resolution; some of the people even accompanied him on his homeward way. When they had parted at last, the uncle looked after them with his face shining as with an inward light. Heidi looked up to him and said: “Grandfather, you have never looked so beautiful!”

“Do you think so, child?” he said with a smile. “You see, Heidi, I am more happy than I deserve; to be at peace with God and men makes one’s heart feel light. God has been good to me, to send you back.”

When they arrived at Peter’s hut, the grandfather opened the door and entered. “How do you do, grandmother,” he called out. “I think we must start to mend again, before the fall wind comes.”

“Oh my God, the uncle!” exclaimed the grandmother in joyous surprise. “How happy I am to be able to thank you for what you have done, uncle! Thank you, God bless you for it.”

With trembling joy the grandmother shook hands with her old friend. “There is something else I want to say to you, uncle,” she continued. “If I have ever hurt you in any way, do not punish me. Do not let Heidi go away again before I die. I cannot tell you what Heidi means to me!” So saying, she held the clinging child to her.

“No danger of that, grandmother, I hope we shall all stay together now for many years to come.”

Brigida now showed Heidi’s feather hat to the old man and asked him to take it back. But the uncle asked her to keep it, since Heidi had given it to her.

“What blessings this child has brought from Frankfurt,” Brigida said. “I often wondered if I should not send our little Peter too. What do you think, uncle?”

The uncle’s eyes sparkled with fun, when he replied: “I am sure it would not hurt Peter; nevertheless I should wait for a fitting occasion before I sent him.”

The next moment Peter himself arrived in great haste. He had a letter for Heidi, which had been given to him in the village. What an event, a letter for Heidi! They all sat down at the table while the child read it aloud. The letter was from Clara Sesemann, who wrote that everything had got so dull since Heidi left. She said that she could not stand it very long, and therefore her father had promised to take her to Ragatz this coming fall. She announced that Grandmama was coming too, for she wanted to see Heidi and her grandfather. Grandmama, having heard about the rolls, was sending some coffee, too, so that the grandmother would not have to eat them dry. Grandmama also insisted on being taken to the grandmother herself when she came on her visit.

Great was the delight caused by this news, and what with all the questions and plans that followed, the grandfather himself forgot how late it was. This happy day, which had united them all, caused the old woman to say at parting: “The most beautiful thing of all, though, is to be able to shake hands again with an old friend, as in days gone by; it is a great comfort to find again, what we have treasured. I hope you’ll come soon again, uncle. I am counting on the child for tomorrow.”

This promise was given. While Heidi and her grandfather were on their homeward path, the peaceful sound of evening bells accompanied them. At last they reached the cottage, which seemed to glow in the evening light.

Heidi Chapter 14 part 1

On Sunday When The Church Bells Ring

Heidi was standing under the swaying fir-trees, waiting for her grandfather to join her. He had promised to bring up her trunk from the village while she went in to visit the grandmother. The child was longing to see the blind woman again and to hear how she had liked the rolls. It was Saturday, and the grandfather had been cleaning the cottage. Soon he was ready to start. When they had descended and Heidi entered Peter’s hut, the grandmother called lovingly to her: “Have you come again, child?”

She took hold of Heidi’s hand and held it tight. Grandmother then told the little visitor how good the rolls had tasted, and how much stronger she felt already. Brigida related further that the grandmother had only eaten a single roll, being so afraid to finish them too soon. Heidi had listened attentively, and said now: “Grandmother, I know what I shall do. I am going to write to Clara and she’ll surely send me a whole lot more.”

But Brigida remarked: “That is meant well, but they get hard so soon. If I only had a few extra pennies, I could buy some from our baker. He makes them too, but I am hardly able to pay for the black bread.”

Heidi’s face suddenly shone. “Oh, grandmother, I have an awful lot of money,” she cried. “Now I know what I’ll do with it. Every day you must have a fresh roll and two on Sundays. Peter can bring them up from the village.”

“No, no, child,” the grandmother implored. “That must not be. You must give it to grandfather and he’ll tell you what to do with it.”

But Heidi did not listen but jumped gaily about the little room, calling over and over again: “Now grandmother can have a roll every day. She’ll get well and strong, and,” she called with fresh delight, “maybe your eyes will see again, too, when you are strong and well.”

The grandmother remained silent, not to mar the happiness of the child. Seeing the old hymn-book on the shelf, Heidi said:

“Grandmother, shall I read you a song from your book now? I can read quite nicely!” she added after a pause.

“Oh yes, I wish you would, child. Can you really read?”

Heidi, climbing on a chair, took down the dusty book from a shelf. After she had carefully wiped it off, she sat down on a stool.

“What shall I read, grandmother?”

“Whatever you want to,” was the reply. Turning the pages, Heidi found a song about the sun, and decided to read that aloud. More and more eagerly she read, while the grandmother, with folded arms, sat in her chair. An expression of indescribable happiness shone in her countenance, though tears were rolling down her cheeks. When Heidi had repeated the end of the song a number of times, the old woman exclaimed: “Oh, Heidi, everything seems bright to me again and my heart is light. Thank you, child, you have done me so much good.”

Heidi looked enraptured at the grandmother’s face, which had changed from an old, sorrowful expression to a joyous one.

She seemed to look up gratefully, as if she could already behold the lovely, celestial gardens told of in the hymn.

Soon the grandfather knocked on the window, for it was time to go. Heidi followed quickly, assuring the grandmother that she would visit her every day now; on the days she went up to the pasture with Peter, she would return in the early afternoon, for she did not want to miss the chance to make the grandmother’s heart joyful and light. Brigida urged Heidi to take her dress along, and with it on her arm the child joined the old man and immediately told him what had happened.

On hearing of her plan to purchase rolls for the grandmother every day, the grandfather reluctantly consented.

At this the child gave a bound, shouting: “Oh grandfather, now grandmother won’t ever have to eat hard, black bread any more. Oh, everything is so wonderful now! If God Our Father had done immediately what I prayed for, I should have come home at once and could not have brought half as many rolls to grandmother. I should not have been able to read either. Grandmama told me that God would make everything much better than I could ever dream. I shall always pray from now on, the way grandmama taught me. When God does not give me something I pray for, I shall always remember how everything has worked out for the best this time. We’ll pray every day, grandfather, won’t we, for otherwise God might forget us.”

“And if somebody should forget to do it?” murmured the old man.

“Oh, he’ll get on badly, for God will forget him, too. If he is unhappy and wretched, people don’t pity him, for they will say: ‘he went away from God, and now the Lord, who alone can help him, has no pity on him’.”

“Is that true, Heidi? Who told you so?”

“Grandmama explained it all to me.”

After a pause the grandfather said: “Yes, but if it has happened, then there is no help; nobody can come back to the Lord, when God has once forgotten him.”

“But grandfather, everybody can come back to Him; grandmama told me that, and besides there is the beautiful story in my book. Oh, grandfather, you don’t know it yet, and I shall read it to you as soon as we get home.”

The grandfather had brought a big basket with him, in which he carried half the contents of Heidi’s trunk; it had been too large to be conveyed up the steep ascent. Arriving at the hut and setting down his load, he had to sit beside Heidi, who was ready to begin the tale. With great animation Heidi read the story of the prodigal son, who was happy at home with his father’s cows and sheep. The picture showed him leaning on his staff, watching the sunset. “Suddenly he wanted to have his own inheritance, and be able to be his own master. Demanding the money from his father, he went away and squandered all. When he had nothing in the world left, he had to go as servant to a peasant, who did not own fine cattle like his father, but only swine; his clothes were rags, and for food he only got the husks on which the pigs were fed. Often he would think what a good home he had left, and when he remembered how good his father had been to him and his own ungratefulness, he would cry from repentance and longing. Then he said to himself: ‘I shall go to my father and ask his forgiveness.’ When he approached his former home, his father came out to meet him—”

Heidi Chapter 13 – Part 2

On A Summer Evening continued…

They conversed no more, and Heidi began to tremble with excitement when she recognized all the trees on the road and the lofty peaks of the mountains. Sometimes she felt as if she could not sit still any longer, but had to jump down and run with all her might. They arrived at the village at the stroke of five. Immediately a large group of women and children surrounded the cart, for the trunk and the little passenger had attracted everybody’s notice. When Heidi had been lifted down, she found herself held and questioned on all sides. But when they saw how frightened she was, they let her go at last. The baker had to tell of Heidi’s arrival with the strange gentleman, and assured all the people that Heidi loved her grandfather with all her heart, let the people say what they would about him.

Heidi, in the meantime, was running up the path; from time to time she was obliged to stop, for her basket was heavy and she lost her breath. Her one idea was: “If only grandmother still sits in her corner by her spinning wheel!—Oh, if she should have died!” When the child caught sight of the hut at last, her heart began to beat. The quicker she ran, the more it beat, but at last she tremblingly opened the door. She ran into the middle of the room, unable to utter one tone, she was so out of breath.

“Oh God,” it sounded from one corner, “our Heidi used to come in like that. Oh, if I just could have her again with me before I die. Who has come?”

“Here I am! grandmother, here I am!” shouted the child, throwing herself on her knees before the old woman. She seized her hands and arms and snuggling up to her did not for joy utter one more word. The grandmother had been so surprised that she could only silently caress the child’s curly hair over and over again. “Yes, yes,” she said at last, “this is Heidi’s hair, and her beloved voice. Oh my God, I thank Thee for this happiness.” Out of her blind eyes big tears of joy fell down on Heidi’s hand. “Is it really you, Heidi? Have you really come again?”

“Yes, yes, grandmother,” the child replied. “You must not cry, for I have come and will never leave you any more. Now you won’t have to eat hard black bread any more for a little while. Look what I have brought you.”

Heidi put one roll after another into the grandmother’s lap.

“Ah, child, what a blessing you bring to me!” the old woman cried. “But you are my greatest blessing yourself, Heidi!” Then, caressing the child’s hair and flushed cheeks, she entreated: “Just say one more word, that I may hear your voice.”

While Heidi was talking, Peter’s mother arrived, and exclaimed in her amazement: “Surely, this is Heidi. But how can that be?”

The child rose to shake hands with Brigida, who could not get over Heidi’s splendid frock and hat.

“You can have my hat, I don’t want it any more; I have my old one still,” Heidi said, pulling out her old crushed straw hat. Heidi had remembered her grandfather’s words to Deta about her feather hat; that was why she had kept her old hat so carefully. Brigida at last accepted the gift after a great many remonstrances. Suddenly Heidi took off her pretty dress and tied her old shawl about her. Taking the grandmother’s hand, she said: “Good-bye, I must go home to grandfather now, but I shall come again tomorrow. Good-night, grandmother.”

“Oh, please come again to-morrow, Heidi,” implored the old woman, while she held her fast.

“Why did you take your pretty dress off?” asked Brigida.

“I’d rather go to grandfather that way, or else he might not know me any more, the way you did.”

Brigida accompanied the child outside and said mysteriously: “He would have known you in your frock; you ought to have kept it on. Please be careful, child, for Peter tells us that the uncle never says a word to anyone and always seems so angry.” But Heidi was unconcerned, and saying good-night, climbed up the path with the basket on her arm. The evening sun was shining down on the grass before her. Every few minutes Heidi stood still to look at the mountains behind her. Suddenly she looked back and beheld such glory as she had not even seen in her most vivid dream. The rocky peaks were flaming in the brilliant light, the snow-fields glowed and rosy clouds were floating overhead. The grass was like an expanse of gold, and below her the valley swam in golden mist. The child stood still, and in her joy and transport tears ran down her cheeks. She folded her hands, and looking up to heaven, thanked the Lord that He had brought her home again. She thanked Him for restoring her to her beloved mountains,—in her happiness she could hardly find words to pray. Only when the glow had subsided, was Heidi able to follow the path again.

She climbed so fast that she could soon discover, first the tree-tops, then the roof, finally the hut. Now she could see her grandfather sitting on his bench, smoking a pipe. Above the cottage the fir-trees gently swayed and rustled in the evening breeze. At last she had reached the hut, and throwing herself in her grandfather’s arms, she hugged him and held him tight. She could say nothing but “Grandfather! grandfather! grandfather!” in her agitation.

The old man said nothing either, but his eyes were moist, and loosening Heidi’s arms at last, he sat her on his knee. When he had looked at her a while, he said: “So you have come home again, Heidi? Why? You certainly do not look very cityfied! Did they send you away?”

“Oh no, you must not think that, grandfather. They all were so good to me; Clara, Mr. Sesemann and grandmama. But grandfather, sometimes I felt as if I could not bear it any longer to be away from you! I thought I should choke; I could not tell any one, for that would have been ungrateful. Suddenly, one morning Mr. Sesemann called me very early, I think it was the doctor’s fault and—but I think it is probably written in this letter;” with that Heidi brought the letter and the bank-roll from her basket, putting them on her grandfather’s lap.

“This belongs to you,” he said, laying the roll beside him. Having read the letter, he put it in his pocket.

“Do you think you can still drink milk with me, Heidi?” he asked, while he stepped into the cottage. “Take your money with you, you can buy a bed for it and clothes for many years.”

“I don’t need it at all, grandfather,” Heidi assured him; “I have a bed and Clara has given me so many dresses that I shan’t need any more all my life.”

“Take it and put it in the cupboard, for you will need it some day.”

Heidi obeyed, and danced around the hut in her delight to see all the beloved things again. Running up to the loft, she exclaimed in great disappointment: “Oh grandfather, my bed is gone.”

“It will come again,” the grandfather called up from below; “how could I know that you were coming back? Get your milk now!”

Heidi, coming down, took her old seat. She seized her bowl and emptied it eagerly, as if it was the most wonderful thing she had ever tasted. “Grandfather, our milk is the best in all the world.”

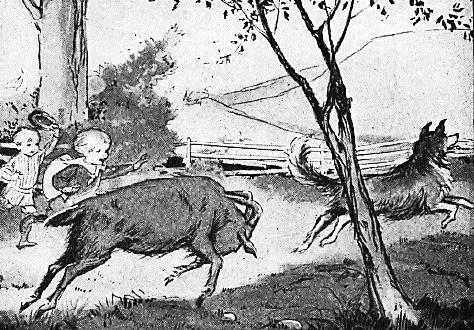

Suddenly Heidi, hearing a shrill whistle, rushed outside, as Peter and all his goats came racing down. Heidi greeted the boy, who stopped, rooted to the spot, staring at her. Then she ran into the midst of her beloved friends, who had not forgotten her either. Schwänli and Bärli bleated for joy, and all her other favorites pressed near to her. Heidi was beside herself with joy, and caressed little Snowhopper and patted Thistlefinch, till she felt herself pushed to and fro among them.

“Peter, why don’t you come down and say good-night to me?” Heidi called to the boy.

“Have you come again?” he exclaimed at last. Then he took Heidi’s proffered hand and asked her, as if she had been always there: “Are you coming up with me tomorrow?”

“No, tomorrow I must go to grandmother, but perhaps the day after.”

Peter had a hard time with his goats that day, for they would not follow him. Over and over again they came back to Heidi, till she entered the shed with Bärli and Schwänli and shut the door.

When Heidi went up to her loft to sleep, she found a fresh, fragrant bed waiting for her; and she slept better that night than she had for many, many months, for her great and burning longing had been satisfied. About ten times that night the grandfather rose from his couch to listen to Heidi’s quiet breathing. The window was filled up with hay, for from now on the moon was not allowed to shine on Heidi any more. But Heidi slept quietly, for she had seen the flaming mountains and had heard the fir-trees roar.

Swiss Family Robinson Chapter 47

Chapter 47

We soon arrived at Family Bridge, where I had some hopes of meeting Francis, and perhaps his mother, who was beginning to walk very well; but I was disappointed they were not there. Yet I was not uneasy, for they were neither certain of the hour of our return, nor of the way we might take. I expected, however, to find them in the colonnade they were not there. I hastily entered the house; I called aloud, “Elizabeth! Francis! where are you?” No one answered. A mortal terror seized me and for a moment I could not move.

“They will be in the grotto,” said Ernest.

“Or in the garden,” said Fritz.

“Perhaps on the shore,” cried Jack; “my mother likes to watch the waves, and Francis may be gathering shells.”

These were possibilities. My sons flew in all directions in search of their mother and brother. I found it impossible to move, and was obliged to sit down. I trembled, and my heart beat till I could scarcely breathe. I did not venture to dwell on the extent of my fears, or, rather, I had no distinct notion of them. I tried to recover myself. I murmured, “Yes at the grotto, or the garden they will return directly.” Still, I could not compose myself. I was overwhelmed with a sad presentiment of the misfortune which impended over me. It was but too soon realized. My sons returned in fear and consternation. They had no occasion to tell me the result of their search; I saw it at once, and, sinking down motionless, I cried, “Alas! they are not there!”

Jack returned the last, and in the most frightful state; he had been at the sea-shore, and, throwing himself into my arms, he sobbed out

“The natives have been here, and carried away my mother and Francis; perhaps they have devoured them; I have seen the marks of their horrible feet on the sands, and the print of dear Francis’s boots.”

This account at once recalled me to strength and action.

“Come, my children, let us fly to save them. God will pity our sorrow, and assist us. He will restore them. Come, come!”

They were ready in a moment. But a distracting thought seized me. Had they carried off the pinnace? if so, every hope was gone. Jack, in his distress, had never thought of remarking this; but, the instant I named it, Fritz and he ran to ascertain the important circumstance, Ernest, in the mean time, supporting me, and endeavouring to calm me.

“Perhaps,” said he, “they are still in the island. Perhaps they may have fled to hide themselves in some wood, or amongst the reeds. Even if the pinnace be left, it would be prudent to search the island from end to end before we leave it. Trust Fritz and me, we will do this; and, even if we find them in the hands of the enemy, we will recover them. Whilst we are off on this expedition, you can be preparing for our voyage, and we will search the world from one end to the other, every country and every sea, but we will find them. And we shall succeed. Let us put our whole trust in God. He is our Father, he will not try us beyond our strength.”

I embraced my child, and a flood of tears relieved my overcharged heart. My eyes and hands were raised to Heaven; my silent prayers winged their flight to the Almighty, to him who tries us and consoles us. A ray of hope seemed to visit my mind, when I heard my boys cry out, as they approached

“The pinnace is here! they have not carried that away!”

I fervently thanked God it was a kind of miracle; for this pretty vessel was more tempting than the canoe. Perhaps, as it was hidden in a little creek between the rocks, it had escaped their observation; perhaps they might not know how to manage it; or they might not be numerous enough. No matter, it was there, and might be the means of our recovering the beloved objects those barbarians had torn from us. How gracious is God, to give us hope to sustain us in our afflictions! Without hope, we could not live; it restores and revives us, and, even if never realized below, accompanies us to the end of our life, and beyond the grave!

I imparted to my eldest son the idea of his brother, that they might be concealed in some part of the island; but I dared not rely on this sweet hope. Finally, as we ought not to run the risk of abandoning them, if they were still here, and perhaps in the power of the natives, I consented that my two eldest sons should go to ascertain the fact. Besides, however impatient I was, I felt that a voyage such as we were undertaking into unknown seas might be of long duration, and it was necessary to make some preparations I must think on food, water, arms, and many other things. There are situations in life which seize the heart and soul, rendering us insensible to the wants of the body this we now experienced.

We had just come from a painful journey, on foot, of twenty-four hours, during which we had had little rest, and no sleep. Since morning we had eaten nothing but some morsels of the bread-fruit; it was natural that we should be overcome with fatigue and hunger. But we none of us had even thought of our own state we were supported, if I may use the expression, by our despair. At the moment that my sons were going to set out, the remembrance of their need of refreshment suddenly occurred to me, and I besought them to rest a little, and take something; but they were too much agitated to consent. I gave Fritz a bottle of Canary, and some slices of roast mutton I met with, which he put in his pocket. They had each a loaded musket, and they set out, taking the road along the rocks, where the most hidden retreats and most impenetrable woods lay; they promised me to fire off their pieces frequently to let their mother know they were there, if she was hidden among the rocks they took also one of the dogs. Flora we could not find, which made us conclude she had followed her mistress, to whom she was much attached.

As soon as my eldest sons had left us, I made Jack conduct me to the shore where he had seen the footmarks, that I might examine them, to judge of their number and direction. I found many very distinct, but so mingled, I could come to no positive conclusion. Some were near the sea, with the foot pointing to the shore; and amongst these Jack thought he could distinguish the boot-mark of Francis. My wife wore very light boots also, which I had made for her; they rendered stockings unnecessary, and strengthened her ankles. I could not find the trace of these; but I soon discovered that my poor Elizabeth had been here, from a piece torn from an apron she wore, made of her own cotton, and dyed red. I had now not the least doubt that she was in the canoe with her son. It was a sort of consolation to think they were together; but how many mortal fears accompanied this consolation! Oh! was I ever to see again these objects of my tenderest affection!

Certain now that they were not in the island, I was impatient for the return of my sons, and I made every preparation for our departure. The first thing I thought of was the wrecked chest, which would furnish me with means to conciliate the natives, and to ransom my loved ones. I added to it everything likely to tempt them; utensils, stuffs, trinkets; I even took with me gold and silver coin, which was thrown on one side as useless, but might be of service to us on this occasion. I wished my riches were three times as much as they were, that I might give all in exchange for the life and liberty of my wife and son. I then turned my thoughts on those remaining to me: I took, in bags and gourds, all that we had left of cassava-bread, manioc-roots, and potatoes; a barrel of salt-fish, two bottles of rum, and several jars of fresh water. Jack wept as he filled them at his fountain, which he perhaps might never see again, any more than his dear Valiant, whom I set at liberty, as well as the cow, ass, buffalo, and the beautiful donkey. These docile animals were accustomed to us and our attentions, and they remained in their places, surprised that they were neither harnessed nor mounted. We opened the poultry-yard and pigeon-cote. The flamingo would not leave us, it went and came with us from the house to the pinnace. We took also oil, candles, fuel, and a large iron pot to cook our provisions in. For our defense, I took two more guns, and a small barrel of powder, all we had left. I added besides some changes of linen, not forgetting some for my dear wife, which I hoped might be needed. The time fled rapidly while we were thus employed; night came on, and my sons returned not. My grief was inconceivable; the island was so large and woody, that they might have lost themselves, or the natives might have returned and encountered them. After twenty hours of frightful terror, I heard the report of a gun alas! only one report! it was the signal agreed on if they returned alone; two if they brought their mother; three if Francis also accompanied them; but I expected they would return alone, and I was still grateful. I ran to meet them; they were overcome with fatigue and vexation.

They begged to set out immediately, not to lose one precious moment; they were now sure the island did not contain those they lamented, and they hoped I would not return without discovering them, for what would the island be to us without our loved ones? Fritz, at that moment, saw his dear Lightfoot capering round him, and could not help sighing as he caressed him, and took leave of him.

“May I find thee here,” said he, “where I leave thee in such sorrow; and I will bring back thy young master,” added he, turning to the bull, who was also approaching him.

He then begged me again to set out, as the moon was just rising in all her majesty.

“The queen of night,” said Ernest; “will guide us to the queen of our island, who is perhaps now looking up to her, and calling on us to help her.”

“Most assuredly,” said I, “she is thinking on us; but it is on God she is calling for help. Let us join her in prayer, my dear children, for herself and our dear Francis.”

They fell on their knees with me, and I uttered the most fervent and earnest prayer that ever human heart poured forth; and I rose with confidence that our prayers were heard. I proceeded with new courage to the creek that contained our pinnace, where Jack arranged all we had brought; we rowed out of the creek, and when we were in the bay, we held a council to consider on which side we were to commence our search. I thought of returning to the great bay, from whence our canoe had been taken; my sons, on the contrary, thought that these islanders, content with their acquisition, had been returning homewards, coasting along the island, when an unhappy chance had led their mother and brother to the shore, where the natives had seen them, and carried them off. At the most, they could but be a day before us; but that was long enough to fill us with dreadful anticipations. I yielded to the opinion of my sons, which had a great deal of reason on its side, besides the wind was favourable in that direction; and, abandoning ourselves in full confidence to Almighty God, we spread our sails, and were soon in the open sea.

Peter and Polly: Starting for the Fair

Starting for the Fair

Polly ran into the house from school one day. She banged all the doors.

“Next week is fair week! Next week is fair week!” she shouted.

Peter was in the house. He heard Polly. “Next week is fair week! Next week is fair week!” he shouted, too.

“How do you know, Peter?” asked Polly.

“Because you said so,” answered Peter. “Besides, the blacksmith said so. His horses are going to the fair to get blue ribbons. Do horses like to go to the fair? If we go, shall we get blue ribbons?”

Father laughed. “You certainly are a prize,” he said. “You ought to get a blue ribbon.”

“Then will you take us so that we can?” asked Peter.

And Polly said, “Oh, will you take us? School closes for two days so that all the children can go.”

“Yes,” said father. “I mean to take you. Mother is going, too. If it does not rain, we shall have a good time.”

“Goody, goody!” cried both children.

“Shall we drive Mary?” asked Polly. “Tim is going on the train.”

“I think so,” said father. “But we may go on the train. That will be just as mother says. You must ask her.”

“Are you going on the train, mother?” asked Peter. “I wish to go on the train.”

“If we do, you will have to help carry the luncheon,” said mother.

“Oh, shall we take things to eat?” shouted Peter. “Goody, goody! Then let us go in our carriage.”

“I think that will be easier,” said mother.

The day of the fair was warm and bright. Mother and father were up early. So were Peter and Polly.

Mother got the breakfast, and washed the dishes, and put up the luncheon. Father fed the horse, and milked the cow, and fed the hens.

Polly made the beds. She was in a great hurry to get them done.

She smoothed out all the wrinkles in mother’s bed. She smoothed out all the wrinkles in father’s bed. She smoothed out all the wrinkles in Peter’s bed.

When she came to her own bed she said, “I shall not smooth out all my wrinkles. It takes too long. I wish to be downstairs and know what is going on.”

You see that mother and father and Polly were all busy. And Peter was busy, too. He was busy getting into everybody’s way.

He stood just where mother wished to walk. Then he went upstairs and stood just where Polly wished to walk. But he did not mean to do so.

At last mother said, “Peter, why don’t you run out and sit in the carriage? In a few minutes, father will harness Mary. I am almost ready now.”

“I will,” said Peter. He got his hat and his coat. Father had drawn the two-seated carriage out of the barn. Peter climbed into it.

He waited a long, long time. He thought that he had waited all the morning. But it was really only half an hour.

At last Polly came. Then father brought out the luncheon basket. He harnessed Mary. Mother came out of the side door. She was ready, too.

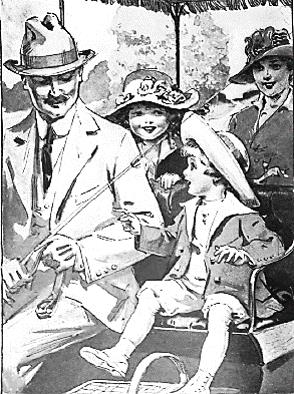

Mother and Polly sat on the back seat. Father and Peter sat in front.

Down the hill they went. Past the store and through the woods, past Farmer Brown’s and on, on, on to Large Village the road ran.

“I never was so happy before in all my life,” said Polly. “Just think! We are going to the fair, and we are going to have a picnic, too. I must jump up and down.”

“Jump then,” said mother. “But remember the blacksmith’s pig. Do not jump out.”

Through Large Village they went. Then the road became crowded. There were many carriages. There were more automobiles.

They had to drive very slowly. But at last they came in sight of the Fair Grounds.

Heidi Chapter 13

On A Summer Evening

Mr. Sesemann, going upstairs in great agitation, knocked at the housekeeper’s door. He asked her to hurry, for preparations for a journey had to be made. Miss Rottenmeier obeyed the summons with the greatest indignation, for it was only half-past four in the morning. She dressed in haste, though with great difficulty, being nervous and excited. All the other servants were summoned likewise, and one and all thought that the master of the house had been seized by the ghost and that he was ringing for help. When they had all come down with terrified looks, they were most surprised to see Mr. Sesemann fresh and cheerful, giving orders. John was sent to get the horses ready and Tinette was told to prepare Heidi for her departure while Sebastian was commissioned to fetch Heidi’s aunt. Mr. Sesemann instructed the housekeeper to pack a trunk in all haste for Heidi.

Miss Rottenmeier experienced an extreme disappointment, for she had hoped for an explanation of the great mystery. But Mr. Sesemann, evidently not in the mood to converse further, went to his daughter’s room. Clara had been wakened by the unusual noises and was listening eagerly. Her father told her of what had happened and how the doctor had ordered Heidi back to her home, because her condition was serious and might get worse. She might even climb the roof, or be exposed to similar dangers, if she was not cured at once.

Clara was painfully surprised and tried to prevent her father from carrying out his plan. He remained firm, however, promising to take her to Switzerland himself the following summer, if she was good and sensible now. So the child, resigning herself, begged to have Heidi’s trunk packed in her room. Mr. Sesemann encouraged her to get together a good outfit for her little friend.

Heidi’s aunt had arrived in the meantime. Being told to take her niece home with her, she found no end of excuses, which plainly showed that she did not want to do it; for Deta well remembered the uncle’s parting words. Mr. Sesemann dismissed her and summoned Sebastian. The butler was told to get ready for travelling with the child. He was to go to Basle that day and spend the night at a good hotel which his master named. The next day the child was to be brought to her home.

“Listen, Sebastian,” Mr. Sesemann said, “and do exactly as I tell you. I know the Hotel in Basle, and if you show my card they will give you good accommodations. Go to the child’s room and barricade the windows, so that they can only be opened by the greatest force. When Heidi has gone to bed, lock the door from outside, for the child walks in her sleep and might come to harm in the strange hotel. She might get up and open the door; do you understand?”

“Oh!—Oh!—So it was she?” exclaimed the butler.

“Yes, it was! You are a coward, and you can tell John he is the same. Such foolish men, to be afraid!” With that Mr. Sesemann went to his room to write a letter to Heidi’s grandfather.

Sebastian, feeling ashamed, said to himself that he ought to have resisted John and found out alone.

Heidi was dressed in her Sunday frock and stood waiting for further commands.

Mr. Sesemann called her now. “Good-morning, Mr. Sesemann,” Heidi said when she entered.

“What do you think about it, little one?” he asked her. Heidi looked up to him in amazement.

“You don’t seem to know anything about it,” laughed Mr. Sesemann. Tinette had not even told the child, for she thought it beneath her dignity to speak to the vulgar Heidi.

“You are going home to-day.”

“Home?” Heidi repeated in a low voice. She had to gasp, so great was her surprise.

“Wouldn’t you like to hear something about it?” asked Mr. Sesemann smiling.

“Oh yes, I should like to,” said the blushing child.

“Good, good,” said the kind gentleman. “Sit down and eat a big breakfast now, for you are going away right afterwards.”

The child could not even swallow a morsel, though she tried to eat out of obedience. It seemed to her as if it was only a dream.

“Go to Clara, Heidi, till the carriage comes,” Mr. Sesemann said kindly.

Heidi had been wishing to go, and now she ran to Clara’s room, where a huge trunk was standing.

“Heidi, look at the things I had packed for you. Do you like them?” Clara asked.

There were a great many lovely things in it, but Heidi jumped for joy when she discovered a little basket with twelve round white rolls for the grandmother. The children had forgotten that the moment for parting had come, when the carriage was announced. Heidi had to get all her own treasures from her room yet. The grandmama’s book was carefully packed, and the red shawl that Miss Rottenmeier had purposely left behind. Then putting on her pretty hat, she left her room to say good-bye to Clara. There was not much time left to do so, for Mr. Sesemann was waiting to put Heidi in the carriage. When Miss Rottenmeier, who was standing on the stairs to bid farewell to her pupil, saw the red bundle in Heidi’s hand, she seized it and threw it on the ground. Heidi looked imploringly at her kind protector, and Mr. Sesemann, seeing how much she treasured it, gave it back to her. The happy child at parting thanked him for all his goodness. She also sent a message of thanks to the good old doctor, whom she suspected to be the real cause of her going.

While Heidi was being lifted into the carriage, Mr. Sesemann assured her that Clara and he would never forget her. Sebastian followed with Heidi’s basket and a large bag with provisions. Mr. Sesemann called out: “Happy journey!” and the carriage rolled away.

Only when Heidi was sitting in the train did she become conscious of where she was going. She knew now that she would really see her grandfather and the grandmother again, also Peter and the goats. Her only fear was that the poor blind grandmother might have died while she was away.

The thing she looked forward to most was giving the soft white rolls to the grandmother. While she was musing over all these things, she fell asleep. In Basle she was roused by Sebastian, for there they were to spend the night.

The next morning they started off again, and it took them many hours before they reached Mayenfeld. When Sebastian stood on the platform of the station, he wished he could have travelled further in the train rather than have to climb a mountain. The last part of the trip might be dangerous, for everything seemed half-wild in this country. Looking round, he discovered a small wagon with a lean horse. A broad-shouldered man was just loading up large bags, which had come by the train. Sebastian, approaching the man, asked some information concerning the least dangerous ascent to the Alp. After a while it was settled that the man should take Heidi and her trunk to the village and see to it that somebody would go up with her from there.

Not a word had escaped Heidi, until she now said, “I can go up alone from the village. I know the road.” Sebastian felt relieved, and calling Heidi to him, presented her with a heavy roll of bills and a letter for the grandfather. These precious things were put at the bottom of the basket, under the rolls, so that they could not possibly get lost.

Heidi promised to be careful of them, and was lifted up to the cart. The two old friends shook hands and parted, and Sebastian, with a slightly bad conscience for having deserted the child so soon, sat down on the station to wait for a returning train.

The driver was no other than the village baker, who had never seen Heidi but had heard a great deal about her. He had known her parents and immediately guessed she was the child who had lived with the Alm-Uncle. Curious to know why she came home again, he began a conversation.

“Are you Heidi, the child who lived with the Alm-Uncle?”

“Yes.”

“Why are you coming home again? Did you get on badly?”

“Oh no; nobody could have got on better than I did in Frankfurt.”

“Then why are you coming back?”

“Because Mr. Sesemann let me come.”

“Pooh! why didn’t you stay?”

“Because I would rather be with my grandfather on the Alp than anywhere on earth.”

“You may think differently when you get there,” muttered the baker. “It is strange though, for she must know,” he said to himself.

Peter and Polly: The Circus

The Circus

When Benjamin Bunny grew up, he married his Cousin Flopsy. They had a large family, and they were very improvident and cheerful. I do not remember the separate names of their children; they were generally called the “Flopsy Bunnies.”

When Benjamin Bunny grew up, he married his Cousin Flopsy. They had a large family, and they were very improvident and cheerful. I do not remember the separate names of their children; they were generally called the “Flopsy Bunnies.” As there was not always quite enough to eat,-Benjamin used to borrow cabbages from Flopsy’s brother, Peter Rabbit, who kept a nursery garden.

As there was not always quite enough to eat,-Benjamin used to borrow cabbages from Flopsy’s brother, Peter Rabbit, who kept a nursery garden. Sometimes Peter Rabbit had no cabbages to spare.

Sometimes Peter Rabbit had no cabbages to spare. When this happened, the Flopsy Bunnies went across the field to a rubbish heap, in the ditch outside Mr. McGregor’s garden.

When this happened, the Flopsy Bunnies went across the field to a rubbish heap, in the ditch outside Mr. McGregor’s garden. Mr. McGregor’s rubbish heap was a mixture. There were jam pots and paper bags, and mountains of chopped grass from the mowing machine (which always tasted oily), and some rotten vegetable marrows and an old boot or two. One day-oh joy!-there were a quantity of overgrown lettuces, which had “shot” into flower.The Flopsy Bunnies simply stuffed themselves with lettuces. By degrees, one after another, they were overcome with slumber, and lay down in the mown grass.

Mr. McGregor’s rubbish heap was a mixture. There were jam pots and paper bags, and mountains of chopped grass from the mowing machine (which always tasted oily), and some rotten vegetable marrows and an old boot or two. One day-oh joy!-there were a quantity of overgrown lettuces, which had “shot” into flower.The Flopsy Bunnies simply stuffed themselves with lettuces. By degrees, one after another, they were overcome with slumber, and lay down in the mown grass. Benjamin was not so much overcome as his children. Before going to sleep he was sufficiently wide awake to put a paper bag over his head to keep off the flies.

Benjamin was not so much overcome as his children. Before going to sleep he was sufficiently wide awake to put a paper bag over his head to keep off the flies. The little Flopsy Bunnies slept delightfully in the warm sun. From the lawn beyond the garden came the distant clacketty sound of the mowing machine. The blue-bottles buzzed about the wall, and a little old mouse picked over the rubbish among the jam pots.

The little Flopsy Bunnies slept delightfully in the warm sun. From the lawn beyond the garden came the distant clacketty sound of the mowing machine. The blue-bottles buzzed about the wall, and a little old mouse picked over the rubbish among the jam pots. (I can tell you her name, she was called Thomasina Tittle- mouse, a wood mouse with a long tail.) She rustled across the paper bag, and awakened Benjamin Bunny. The mouse apologized profusely, and said that she knew Peter Rabbit.

(I can tell you her name, she was called Thomasina Tittle- mouse, a wood mouse with a long tail.) She rustled across the paper bag, and awakened Benjamin Bunny. The mouse apologized profusely, and said that she knew Peter Rabbit. While she and Benjamin were talking, close under the wall, they heard a heavy tread above their heads; and suddenly Mr. McGregor emptied out a sackful of lawn mowings right upon the top of the sleeping Flopsy Bunnies! Benjamin shrank down under his paper bag. The mouse hid in a jam pot.

While she and Benjamin were talking, close under the wall, they heard a heavy tread above their heads; and suddenly Mr. McGregor emptied out a sackful of lawn mowings right upon the top of the sleeping Flopsy Bunnies! Benjamin shrank down under his paper bag. The mouse hid in a jam pot. The little rabbits smiled sweetly in their sleep under the shower of grass; they did not awake because the lettuces had been so soporific. They dreamt that their mother Flopsy was tucking them up in a hay bed.

The little rabbits smiled sweetly in their sleep under the shower of grass; they did not awake because the lettuces had been so soporific. They dreamt that their mother Flopsy was tucking them up in a hay bed. Mr. McGregor looked down after emptying his sack. He saw some funny little brown tips of ears sticking up through the lawn mowings. He stared at them for some time. Presently a fly settled on one of them and it moved.Mr. McGregor climbed down on to the rubbish heap-“One, two, three, four! five! six leetle rabbits!” said he as he dropped them into his sack. The Flopsy Bunnies dreamt that their mother was turning them over in bed. They stirred a little in their sleep, but still they did not wake up.

Mr. McGregor looked down after emptying his sack. He saw some funny little brown tips of ears sticking up through the lawn mowings. He stared at them for some time. Presently a fly settled on one of them and it moved.Mr. McGregor climbed down on to the rubbish heap-“One, two, three, four! five! six leetle rabbits!” said he as he dropped them into his sack. The Flopsy Bunnies dreamt that their mother was turning them over in bed. They stirred a little in their sleep, but still they did not wake up. Mr. McGregor tied up the sack and left it on the wall. He went to put away the mowing machine.

Mr. McGregor tied up the sack and left it on the wall. He went to put away the mowing machine. While he was gone, Mrs. Flopsy Bunny (who had remained at home) came across the field. She looked suspiciously at the sack and wondered where everybody was?

While he was gone, Mrs. Flopsy Bunny (who had remained at home) came across the field. She looked suspiciously at the sack and wondered where everybody was? Then the mouse came out of her jam pot, and Benjamin took the paper bag off his head, and they told the doleful tale.Benjamin and Flopsy were in despair, they could not undo the string.

Then the mouse came out of her jam pot, and Benjamin took the paper bag off his head, and they told the doleful tale.Benjamin and Flopsy were in despair, they could not undo the string. But Mrs. Tittlemouse was a resourceful person. She nibbled a hole in the bottom corner of the sack. The little rabbits were pulled out and pinched to wake them. Their parents stuffed the empty sack with three rotten vegetable marrows, an old blackingbrush and two decayed turnips.

But Mrs. Tittlemouse was a resourceful person. She nibbled a hole in the bottom corner of the sack. The little rabbits were pulled out and pinched to wake them. Their parents stuffed the empty sack with three rotten vegetable marrows, an old blackingbrush and two decayed turnips. Then they all hid under a bush and watched for Mr. McGregor.

Then they all hid under a bush and watched for Mr. McGregor. Mr. McGregor came back and picked up the sack, and carried it off. He carried it hanging down, as if it were rather heavy.

Mr. McGregor came back and picked up the sack, and carried it off. He carried it hanging down, as if it were rather heavy. The Flopsy Bunnies followed at a safe distance. They watched him go into his house.

The Flopsy Bunnies followed at a safe distance. They watched him go into his house. And then they crept up to the window to listen.

And then they crept up to the window to listen. Mr. McGregor threw down the sack on the stone floor in a way that would have been extremely painful to the Flopsy Bunnies, if they had happened to have been inside it.They could hear him drag his chair on the flags, and chuckle-“One, two, three, four, five, six leetle rabbits!” said Mr. McGregor.

Mr. McGregor threw down the sack on the stone floor in a way that would have been extremely painful to the Flopsy Bunnies, if they had happened to have been inside it.They could hear him drag his chair on the flags, and chuckle-“One, two, three, four, five, six leetle rabbits!” said Mr. McGregor. “Eh? What’s that? What have they been spoiling now?” enquired Mrs. McGregor.”One, two, three, four, five, six leetle fat rabbits!” repeated Mr. McGregor, counting on his fingers -“one, two, three-“”Don’t you be silly: what do you mean, you silly old man?””In the sack! one, two, three, four, five, six!” replied Mr. McGregor.(The youngest Flopsy Bunny got upon the windowsill.)

“Eh? What’s that? What have they been spoiling now?” enquired Mrs. McGregor.”One, two, three, four, five, six leetle fat rabbits!” repeated Mr. McGregor, counting on his fingers -“one, two, three-“”Don’t you be silly: what do you mean, you silly old man?””In the sack! one, two, three, four, five, six!” replied Mr. McGregor.(The youngest Flopsy Bunny got upon the windowsill.) Mrs. McGregor took hold of the sack and felt it. She said she could feel six, but they must be OLD rabbits, because they were so hard and all different shapes.”Not fit to eat; but the skins will do fine to line my old cloak.””Line your old cloak?” shouted Mr. McGregor-“I shall sell them and buy myself baccy!””Rabbit tobacco! I shall skin them and cut off their heads.”

Mrs. McGregor took hold of the sack and felt it. She said she could feel six, but they must be OLD rabbits, because they were so hard and all different shapes.”Not fit to eat; but the skins will do fine to line my old cloak.””Line your old cloak?” shouted Mr. McGregor-“I shall sell them and buy myself baccy!””Rabbit tobacco! I shall skin them and cut off their heads.” Mrs. McGregor untied the sack and put her hand inside. When she felt the vegetables she became very very angry. She said that Mr. McGregor had “done it a purpose.”And Mr. McGregor was very angry too. One of the rotten marrows came flying through the kitchen window, and hit the youngest Flopsy Bunny.

Mrs. McGregor untied the sack and put her hand inside. When she felt the vegetables she became very very angry. She said that Mr. McGregor had “done it a purpose.”And Mr. McGregor was very angry too. One of the rotten marrows came flying through the kitchen window, and hit the youngest Flopsy Bunny. It was rather hurt.Then Benjamin and Flopsy thought that it was time to go home.

It was rather hurt.Then Benjamin and Flopsy thought that it was time to go home. So Mr. McGregor did not get his tobacco, and Mrs. McGregor did not get her rabbit skins.But next Christmas, Thomasina Tittlemouse got a present of enough rabbit wool to make herself a cloak and a hood, and a handsome muff and a pair of warm mittens.

So Mr. McGregor did not get his tobacco, and Mrs. McGregor did not get her rabbit skins.But next Christmas, Thomasina Tittlemouse got a present of enough rabbit wool to make herself a cloak and a hood, and a handsome muff and a pair of warm mittens.