The Tale of Solomon Owl Chapter II A NEWCOMER

Chapter II A NEWCOMER

Upon his arrival, as a stranger, in Pleasant Valley, Solomon Owl looked about carefully for a place to live. What he wanted especially was a good, dark hole, for he thought that sunshine was very dismal.

Though he was willing to bestir himself enough to suit anybody, when it came to hunting, Solomon Owl did not like to work. He was no busy nest-builder, like Rusty Wren. In his search for a house he looked several times at the home of old Mr. Crow. If it had suited him better, Solomon would not have hesitated to take it for his own. But in the end he decided that it was altogether too light to please him.

That was lucky for old Mr. Crow. And the black rascal knew it, too. He had noticed that Solomon Owl was hanging about the neighborhood. And several times he caught Solomon examining his nest.

But Mr. Crow did not have to worry long. For as it happened, Solomon Owl at last found exactly what he wanted. In an old, hollow hemlock, he came across a cozy, dark cavity. As soon as he saw it he knew that it was the very thing! So he moved in at once. And except for the time that he spent in the meadow–which was considerably later–he lived there for a good many years.

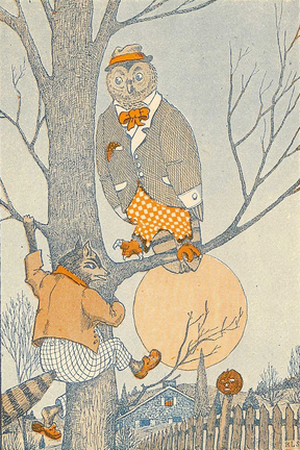

Once Fatty Coon thought that he would drive Solomon out of his snug house and live in it himself. But he soon changed his mind—after one attempt to oust Solomon.

Solomon Owl–so Fatty discovered–had sharp, strong claws and a sharp, strong beak as well, which curled over his face in a cruel hook.

It was really a good thing for Solomon Owl–the fight he had with Fatty Coon. For afterward his neighbors seldom troubled him–except when Jasper Jay brought a crowd of his noisy friends to tease Solomon, or Reddy Woodpecker annoyed him by rapping on his door when he was asleep.

But those rowdies always took good care to skip out of Solomon’s reach. And when Jasper Jay met Solomon alone in the woods at dawn or dusk he was most polite to the solemn old chap. Then it was “Howdy-do, Mr. Owl!” and “I hope you’re well to-day!” And when Solomon Owl turned his great, round, black eyes on Jasper, that bold fellow always felt quite uneasy; and he was glad when Solomon Owl looked away.

If Solomon Owl chanced to hoot on those occasions, Jasper Jay would jump almost out of his bright blue coat. Then Solomon’s deep laughter would echo mockingly through the woods.

You see, though not nearly so wise as he appeared, Solomon Owl knew well enough how to frighten some people.