The Tale of Solomon Owl Chapter IV AN ODD BARGAIN

Chapter IV AN ODD BARGAIN

While Mr. Frog was swallowing nothing rapidly, he was thinking rapidly, too. There was something about Solomon Owl’s big, staring eyes that made Mr. Frog feel uncomfortable. And if he had thought he had any chance of escaping he would have dived into the brook and swum under the bank.

But Solomon Owl was too near him for that. And Mr. Frog was afraid his caller would pounce upon him any moment. So he quickly thought of a plan to save himself. “No doubt—” he began. But Solomon Owl interrupted him.

“There!” cried Solomon. “You can speak, after all. I supposed you’d swallowed your tongue. And I was just waiting to see what you’d do next. I thought maybe you would swallow your head.”

Mr. Frog managed to laugh at the joke, though, to tell the truth, he felt more nervous than ever. He saw what was in Solomon Owl’s mind, for Solomon was thinking of swallowing Mr. Frog’s head himself.

“No doubt–” Mr. Frog resumed–“no doubt you’ve come to ask me to make you a new suit of clothes.”

Now, Solomon Owl had had no such idea at all. But when it was mentioned to him, he rather liked it. “Will you?” he inquired, with a highly interested air.

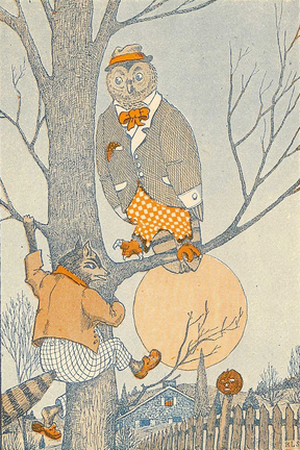

“Why, certainly!” the tailor replied. And for the first time since he had turned his backward somersault into the bulrushes, he smiled widely. “I’ll tell you what I’ll do!” he said. “First, I’ll make you a coat free. And second, if you like it I will then make you a waistcoat and trousers, at double rates.”

Solomon Owl liked the thought of getting a coat for nothing. But for all that, he looked at the tailor somewhat doubtfully. “Will it take you long?” he asked.

“No, indeed!” Mr. Frog told him. “I’ll make your coat while you wait.”

“Oh, I wasn’t going away,” Solomon assured him with an odd look which made Mr. Frog shiver again. “Be quick, please! Because I have some important business to attend to.”

Mr. Frog couldn’t help wondering if it wasn’t he himself that Solomon Owl was going to attend to. In spite of his fears, however, he caught up his shears and set to work to cut up some cloth that hung just outside his door.

“Stop!” Solomon Owl cried in a voice that seemed to shake the very ground.” You haven’t measured me yet!”

“It’s not necessary,” Mr. Frog explained glibly. “I’ve become so skillful that one look at an elegant figure like yours is all that I need.”

Naturally, Mr. Frog’s remark pleased Solomon Owl. And he uttered ten rapid hoots, which served to make Mr. Frog’s fingers fly all the faster. Soon he was sewing Solomon’s coat with long stitches; and though his needle slipped now and then, he did not pause to take out a single stitch. For some reason, Mr. Frog was in a great hurry.

Solomon Owl did not appear to notice that the tailor was not taking much pains with his sewing. Perhaps Mr. Frog worked so fast that Solomon could not see what he was doing.

Anyhow, he was delighted when Mr. Frog suddenly cried:

“It’s finished!” And then he tossed the coat to Solomon. “Try it on!” he said. “I want to see how well it fits you.”

Solomon Owl held up the garment and looked at it very carefully. And as he examined it a puzzled look came over his great pale face.

There was something about his new coat that he did not understand.