Peter and Polly in Winter

PETER AND POLLY IN WINTER

BY ROSE LUCIA

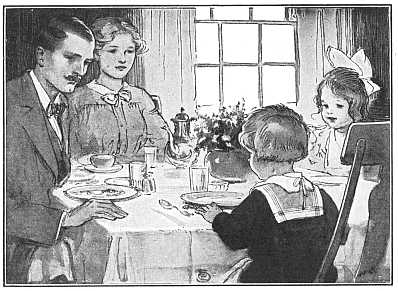

“Peter and Polly in Winter” by Rose Lucia is a children’s story written in the early 20th century. This book is part of a series that likely follows the adventures of Peter and his older sister Polly throughout the seasons. The narrative focuses on the joys of winter, highlighting the children’s imaginative play, their love for nature, and their interactions with animals and family. The opening of the story introduces Peter and Polly, who live in a picturesque white house in the country, surrounded by fields and woods. As winter approaches, Peter expresses his excitement about the coming snow and the magical snowflakes he lovingly refers to as “white butterflies.” With the Story Lady’s encouragement, he eagerly anticipates winter adventures, including watching birds migrate and seeing the first snowfall. The engaging dialogue between the siblings and their father sets the stage for a wholesome exploration of winter activities such as sledding and making snowmen, showcasing themes of family bonds, kindness to animals, and the beauty of the natural world.

Peter And Polly (In winter)

The Birds’ Game of Tag

The Stone-wall Post Office

Playing In the Leaves

How The Leaves Came Down

The Bonfire

The Hen That Helped Peter

The First Ice

The Three Guesses

The First Snowstorm

The Star Snowflake

How Peter Helped Grandmother

The Snow Man

Peter’s Dream

Cutting The Christmas Tree

The Give-away Box

Christmas Morning

The Snow House

The Fall Of The Igloo

Pulling Peter’s Tooth

Driving With Father

The Stag

Polly’s Bird Party

The New Sled

Brownie

Dish-pan Sleds

Cat And Copy-cat

Polly’s Snowshoes

The Woods In Winter

The Winter Picnic

The Sewing Lesson

Fishing Through The Ice

Making Molasses Candy

Grandmother’s Birthday Party

Around The Open Fire