Posts tagged ‘Pilgrims’

During all the early years of the Virginia colony the people were fed and clothed out of a common stock of provisions. They were also obliged to work for this stock. No division was made of the land, nor could the industrious man get any profit by his hard work. The laziest man was as well off as the one who worked hardest, and under this arrangement men neglected their work, and the colony was always poor. The men had been promised that after five years they should have land of their own and be free, but this promise was not kept. In 1614 Sir Thomas Dale gave to some who had been longest in Virginia three acres of ground apiece, and allowed them one month in the year to work on their little patches. For this they must support themselves and give the rest of their work to the common stock. This arrangement made them more industrious. But the cruel military laws put in force by the governor made Virginia very unpopular.

The Spanish in Florida and the French in Canada

The English were not the only people who had colonies in North America. The Spaniards, who claimed the whole continent, had planted a colony at Saint Au’-gus-tine, in Florida, in 1565, forty-two years before the first English colony Jamestown. Saint Augustine is thus the oldest city in the United States. But the Spaniards were too busy in Mexico and in Central and South America to push their settlements farther to the north, though they were very jealous of the English colonies, and especially of South Carolina and Georgia.

The French laid claim also to a large part of North America. They tried to plant a colony in Canada in 1549, and afterward made some other attempts that failed. Quebec [kwebec’] was founded by a great French explorer, Champlain, in 1608, the very year after the English settled at Jamestown. At Quebec the real settlement of Canada was begun, and it was always the capital of the vast establishments of the French in America.

The French, like the English, were trying to find the Pacific Ocean, and they were much more daring in their explorations than the English colonists, whose chief business was farming. A French explorer named Joliet [zhol-yay] reached the Mississippi in 1673, and another Frenchman, La Salle [lah-sahl], explored the great country west of the Alleghany Mountains, and discovered the Ohio. After many disasters and failures, La Salle succeeded in reaching the mouth of the Mississippi. Father Hennepin, a priest, explored the upper Mississippi. The French then laid claim to all the country west of the Alleghanies. Over the region they established posts and mission-houses, while the English contented themselves with multiplying their farming settlements east of the mountains.

When La Salle reached the mouth of the Mississippi, he took possession of the country in the name of Louis XIV., and called it Louisiana, in honor of that king. The settlement of Louisiana was begun in 1699. The French held the St. Lawrence and the Mississippi, the two great water-ways of North America, and they controlled most of the American Indian tribes by means of missionaries and traders. They endeavored to connect Canada and Louisiana by a chain of fortified posts, and so to hold for France an empire, in the heart of America, larger than France itself.

But the weakness of the French in America lay in the fewness of their people. Canada, the oldest of their colonies, was in a country too cold to be a prosperous farming country in that day. Besides, its growth was checked by the system of lordships with tenants, which some of the English colonies had also tried. But inferior as the French were in numbers, they were strong in their military character; they were almost all soldiers. The English were divided into colonies, and could never be made to act together; but the French, from Canada to the Mississippi, were absolutely subjected to their governors.

The French influenced and leveraged the American Indians to push back against the English colonies. The great business of the French in Canada was the fur trade, and this was pushed with an energy that quite left the English traders behind. The French drew furs from the shores of Lake Superior and from beyond the Mississippi. The French traders gained great influence over the American Indians. The English treated the American Indians as inferiors, the French lived among them on terms of equality. The French also gained control of the American Indian tribes by means of missionary priests, who risked their lives and spent their days in the dirty cabins of the American Indians to convert them to European religions. The powerful Iroquois confederacy, known as the “Five Nations,” and afterward as the “Six Nations,” sided with the English, and hated and killed the French. They lived in what is now the State of New York. But the most of the tribes were managed by the French, who sent missionaries to convert them, ambassadors to flatter them, gunsmiths to mend their arms, and military men to teach them to fortify, and to direct their attacks against the settlements of the English. ‘Engraving of Juan Ponce de León’

‘Engraving of Juan Ponce de León’

The wars between the French colony in Canada and the English colonies in what is now the United States were caused partly by wars between France and England in Europe. But there were also causes enough for enmity in the state of affairs on this side of the ocean. First, there was always a quarrel about territory. The French claimed that part of what is now the State of Maine which lies east of the Kennebec River, while the English claimed to the St. Croix. The French also claimed all the country back of the Alleghanies. With a population not more than one twentieth of that of one of the English colonies, they spread their claim over all the country watered by the lakes and the tributaries of the Mississippi, including more than half of the present United States. Second, both France and England wished to control the fisheries of the eastern coast. Third, both the French and the English endeavored to get the entire control of the fur trade. To do this the French tried to win the Iroquois Confederacy to their interest, while the English sought to take the trade of the Western tribes away from the French. Fourth, the French were Catholics and the English mostly Protestants. In that age men were very bigoted about religion, and hated and feared those who differed from them.

SPANISH DISCOVERIES IN FLORIDA

Ponce de Leon [pon’-thay day lay-on; commonly in English, ponss deh lee’-on], an old Spanish explorer, set sail in 1513 from the island of Puerto Rico, to discover a land reported to lie to the northward of Cuba, and which had somehow come to be called Bimini [bee-mcc-nee]. It was said to contain a fountain, by bathing in which an old man would be made young again. On Easter Sunday Ponce discovered the mainland, which he called Florida, from Pascua Florida [pas’-kwah floree’- dah], the Spanish name for Easter Sunday. In 1521 Ponce tried to settle Florida, but his party was attacked and he was mortally wounded by the American Indians. Florida was then believed to be an island. After his death, other Spanish adventurers explored the coast from Labrador southward, and even tried to find goldmines, and plant colonies in the interior of the country. The most famous of these expeditions was that of Hernando de Soto [aer-nan’-do day so’-to], a Spanish explorer, who reached Florida in 1539. He marched through Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi. He was determined to find some land yielding gold, like Mexico and Peru. But he treated the American Indians cruelly, killing some of them wantonly, and forcing others to serve him as slaves. The American Indians, in turn, attacked him again and again, until his party was sadly reduced. De Soto tried to descend the Mississippi River to the Gulf of Mexico, but at the mouth of the Red River he died of a fever. His body was buried m the Mississippi, to keep the American Indians from disfiguring it in revenge. A few of his followers reached the Gulf and got to the Spanish settlements in Mexico.

Life in the Colonial Time

When people first came to this country, they had to take up with such houses as they could get. In Virginia and New England, as in New York and Philadelphia, holes were dug in the ground for dwelling places by some of the first settlers. In some places bark wigwams were made, like those of the American Indians. Sometimes a rudimentary cabin was built of round logs, and without a floor. As time advanced, better houses were built. Some of these were of hewed logs, some of planks, split, or sawed out by hand. The richer people built good houses soon after they came. Most of these had in the middle a large room, called “the hall.”

The chimneys were generally very large, with wide fireplaces. Sometimes there were seats inside the fireplace, and children, sitting on these seats in the evening, amused themselves by watching the stars through the top of the chimney. In the early houses most of the windows had paper instead of glass. This paper was oiled, so as to let light come through.

Except in the houses of rich people the furniture was scant and rough. Benches, stools, and tables were home-made. Beds were often filled with mistletoe, the down from cattail flags, or the feathers of wild-pigeons. People who were not rich brought their food to the table in wooden trenchers, or trays, and ate off wooden plates. Some used square blocks of wood instead of plates. Neither rich nor poor, in England or America, had forks when the first colonies were settled. Meat was cut with a knife and eaten from the fingers. On the tables of well-to-do people pewter dishes were much used, and a row of shining pewter in an open cupboard, called a dresser, was a sign of good housekeeping. The richest people had silverware for use on great occasions. They also had stately furniture brought from England. But carpets were hardly ever seen. The floor of the best room was strewed with sand, which was marked off in ornamental figures. There was no wall-paper until long after 1700, but rich cloths and tapestry hung on the walls of the finest houses.

Cooking was done in front of fireplaces in skillets and on griddles that stood upon legs, so that coals could be put under them, and in pots and kettles that hung over the fire on a swinging crane, so that they could be drawn out or pushed back. Sometimes there was an oven, for baking, built in the side of the chimney. Meat was roasted on a spit in front of the fire. The spit was an iron rod thrust through the piece to be roasted, and turned by a crank. A whole pig or fowl was sometimes hung up before the fire and turned about while it roasted. Often pieces of meat were broiled by throwing them on the live coals.

A mug of home-brewed beer, with bread and cheese, or a porridge of peas or beans, boiled with a little meat, constituted the breakfast of the early colonists. Neither tea nor coffee was known in England or this country until long after the first colonies were settled. When tea came in, it became a fashionable drink, and was served to company from pretty little china cups, set on lacquered tables. Mush, made of Indian-corn meal, was eaten for supper.

In proportion to the population, more wine and spirits were consumed at that time than now. The very strong Madeira wine was drunk at genteel tables. Rum, which from its destructive effects was known everywhere by the nickname of “kill-devil,” was much used then. At every social gathering rum was provided. Hard cider was a common drink. There was much drunkenness. Peach-brandy was used in the Middle and Southern colonies, and was very ruinous to health and morals.

People of wealth made great display in their dress. Much lace and many silver buckles and buttons were worn. Workingmen of all sorts wore leather, deerskin, or coarse canvas breeches. The stockings worn by men were long, the breeches were short, and buckled, or otherwise fastened, at the knees.

Our forefathers traveled about in canoes and little sailing-boats called shallops. Most of the canoes would hold about six men, but some were large enough to hold forty or more. For a long time, there were no roads except the trails and bridle paths created by the American Indians, which could only be traveled on foot or on horseback. Goods were carried on packhorses. When roads were made, wagons came into use.

In a life so hard and busy as that of the early settlers, there was little time for education. The schools were few and generally poor. Boys, when taught at all, learned to read, write, and “cast accounts.” Girls were taught even less. Many of the children born when the colonies were new grew up unable to write their names. There were few books at first, and no newspapers until after 1700. There was little to occupy the mind except the Sunday sermon.

In all the colonies people were very fond of dancing parties. Weddings were times of great excitement and often of much drinking. In some of the colonies wedding festivities were continued for several days. Even funerals were occasions of feasting, and sometimes of excessive drinking In the Middle and Southern colonies the people were fond of horseracing, cock-fighting, and many other cruel sports brought from England. New England people made their militia-trainings the occasions for feasting and amusement, fighting sham battles, and playing many rough, old-fashioned games. Coasting on the snow, skating, and sleighing were first brought into America from Holland by the Dutch settlers in New York. In all the colonies there was a great deal of hunting and fishing. The woods were full of deer and wild turkeys. Flocks of pigeons often darkened the sky, and the rivers were alive with waterfowl and fish.

The Coming of the Puritans

Before the Pilgrims had become comfortably settled in their new home, other English people came to various parts of the New England coast to the northward of Plymouth. About 1623, a few scattering immigrants, mostly fishermen, traders with the American Indians, and timber-cutters, began to settle here and there along the sea about Massachusetts Bay, and later came to the colonies of New Hampshire and Maine.

We have seen in the preceding chapter that the Pilgrims belonged to that party which had separated itself from the Church of England, and so got the name of Separatists. But there were also a great many people who did not like the ceremonies of the established church, but who would not leave it. These were called Puritans, because they sought to purify the Church from what they thought to be wrong. They formed a large part of the English people, and at a later time, under Oliver Cromwell, they got control of England. But at the time of the settlement of New England the party opposed to the Puritans was in power, and the Puritans were persecuted. The little colony of Plymouth, which had now got through its sufferings, showed them a way out of their troubles. Many of the Puritans began to think of emigration.

In 1628, when Plymouth had been settled almost eight years, the Massachusetts Company was formed. This was a company like the Virginia Company that had governed Virginia at first. The Massachusetts Company was controlled by Puritans, and proposed to make settlements within the territory granted to it in New England. The first party sent out by this company settled at Salem in 1628. Others were sent the next year.

But in 1630 a new and bold move was made. The Massachusetts Company resolved to change the place of holding its meetings from London to its new colony in America. This would give the people in the colony, as members of the company, a right to govern themselves. When this proposed change became known in England, many of the Puritans desired to go to America. ‘Portrait of Governor John Winthrop’ by Anthony van Dyck

‘Portrait of Governor John Winthrop’ by Anthony van Dyck

John Winthrop, the new governor, set sail for Massachusetts in 1630, with the charter and about a thousand people, Winthrop and a part of his company settled at Boston, and that became the capital of the colony. No colony was settled more rapidly than Massachusetts. Twenty thousand people came between 1630 and 1640, though the colony was troubled for a while by bitter disputes among its people about matters of religion and by a war with the Pequot Indians.

Some of the Puritans in Massachusetts were dissatisfied with their lands. In 1635 and 1636 these people crossed Connecticut through the unbroken woods to the Connecticut River, and settled the towns of Windsor, Wethersfield, and Hartford, though there were already trading posts on the Connecticut River. This was the beginning of the Colony of Connecticut. Another colony was planted in 1638 in the region about New Haven. It was made up of Puritans under the lead of the Rev. John Davenport. In 1665 New Haven Colony was united with Connecticut.

In 1636 Roger Williams, a minister at Salem, in Massachusetts, was banished from that colony on account of his peculiar views on several subjects, religious and political. One of these was the doctrine that every man had a right to worship God without interference by the government. Williams went to the head of Narragansett Bay and established a settlement on the principle of entire religious liberty. The disputes in Massachusetts resulted in other settlements of banished people on Narragansett Bay, which were all at length united in one colony, from which came the present State of Rhode Island.

The first settlement of New Hampshire was made at Little Harbor, near Portsmouth, in 1623. The population of New Hampshire was increased by those who left the Massachusetts Colony on account of the religious disputes and persecutions there. Other settlers came from England. But there was much confusion and dispute about land-titles and about government, in consequence of which the colony was settled slowly. New Hampshire was several times joined to Massachusetts, but it was finally separated from it in 1741.

As early as 1607, about the time Virginia was settled, a colony was planted in Maine; but this attempt failed. The first permanent settlement in Maine was made at Pemaquid in 1625. Maine submitted to Massachusetts in 1652, but it afterward suffered disorders from conflicting governments until it was at length annexed to Massachusetts by the charter given to that colony in 1692. It remained a part of Massachusetts until it was admitted to the Union as a separate State, in 1820.

The New England colonies were governed under charters, which left them, in general, free from interference from England. Plymouth, Massachusetts, Connecticut, New Haven, and Rhode Island were the only colonies on the continent that had the privilege of choosing their own governors. In 1684 the first Massachusetts charter was taken away, and after that the governors of Massachusetts were appointed by the king, but under a new charter given in 1692 the colony enjoyed the greater part of its old liberties.

JOHN WINTHROP

John Winthrop, the principal founder of Massachusetts, was born in 1588. He was chosen Governor of the Massachusetts Company, and brought the charter and all the machinery of the government with him to America in 1630. He was almost continually governor until he died in 1649. He was a man of great wisdom. When another of the leading men in the colony wrote him an angry letter, he sent it back, saying that “he was not willing to keep such a provocation to ill-feeling by him.” The writer of the letter answered, “Your overcoming yourself has overcome me.” When the colony had little food, and Winthrop’s last bread was in the oven, he divided the small remainder of his flour among the poor. That very day a shipload of provisions came. He dressed plainly, drank little but water, and labored with his hands among his servants. He counted it the great comfort of his life that he had a “loving and dutiful son.” This son was also named John. He was a man of excellent virtues, and was the first Governor of Connecticut.

The Starving Time, and What Followed

The Starving Time, and What Followed

When Captain John Smith went back to England, in 1609, there were nearly five hundred settlers in Virginia. But the settlers soon got into trouble with the American Indians, who lay in the woods and killed every one that ventured out. There was no longer any chance to buy corn, and the food was soon exhausted. The starving people ate the hogs, the dogs, and the horses, even to their skins. Then they ate rats, mice, snakes, toadstools, and whatever they could get that might stop their hunger. One deceased American Indian was eaten, and, as their hunger grew more extreme, they were forced to consume their own dead. Starving men wandered off into the woods and died there; their companions, finding them, devoured them as hungry wild beasts might have done. This was always afterward remembered as “the starving time.”

Along with the people who came at the close of John Smith’s time, there had been sent another shipload of people, with Sir Thomas Gates, a new governor for the colony. This vessel had been shipwrecked, but Gates and his people had got ashore on the Bermuda Islands. These islands had no inhabitants at that time. Here these shipwrecked people lived well on wild hogs. When spring came, they built two little vessels of the cedar trees which grew on the island. These they rigged with sails taken from their wrecked ships, and getting their people aboard they made their way to Jamestown.

When they got there, they found alive but sixty of the four hundred and ninety people left in Virginia in the autumn before, and these sixty would all have died had Gates been ten days later in coming. The food that Gates brought would barely last them sixteen days. So he put the Jamestown people aboard his little cedar ships, intending to sail to Newfoundland, in hope of there falling in with some English fishing-vessels. He set sail down the river, leaving not one English settler on the whole continent of America.

Just before Gates and his people got out of the James River, they met a long boat rowing up toward them. Lord De la Warr had been appointed governor of Virginia, and sent out from England. From some men at the mouth of the river he had learned that Gates and all the people were coming down. He sent his long boat to turn them back again. On a Sunday morning De la Warr landed in Jamestown and knelt on the ground a while in prayer. Then he went to the little church, where he took possession of the government, and rebuked the people for the idleness that had brought them into such suffering. ‘Pocahontas’ After Simon van de Passe

‘Pocahontas’ After Simon van de Passe

During this summer of 1610, a hundred and fifty of the settlers died, and Lord De la Warr, finding himself very ill, left the colony. The next year Sir Thomas Dale took charge, and Virginia was under his government and that of Sir Thomas Gates for five years afterward.

Dale was a soldier, and ruled with extreme severity. He forced the idle settlers to labor, he drove away some of the American Indians, settled some new towns, and he built fortifications. But he was so harsh that the people hated him. He punished men by flogging and by setting them to work in irons for years. Those who rebelled or ran away were put to death in cruel ways; some were burned alive, others were broken on the wheel, and one man, for merely stealing food, was starved to death.

Powhatan, the head chief of the neighboring tribes, gave the colony a great deal of trouble during the first part of Dale’s time. His daughter, Pocahontas, who, as a child, had often played with the boys within the palisades of Jamestown, and had shown herself friendly to Captain Smith and others in their trips among the American Indians, was now a woman grown. While she was visiting a chief named Japazaws, an English captain named Argall hired that chief with a copper kettle to betray her into his hands. Argall took her a captive to Jamestown. Here a settler by the name of John Rolfe married her, after she had received Christian baptism. This marriage brought about a peace between Powhatan and the English settlers in Virginia.

When Dale went back to England in 1616, he took with him some of the American Indians. Pocahontas, who was now called “the Lady Rebecca,” and her husband went to England with Dale. Pocahontas was called a “princess” in England, and received much attention. But she died when about to start back to the colony, leaving a little son.

The same John Rolfe who married Pocahontas was the first Englishman to raise tobacco in Virginia. This he did in 1612. Tobacco brought a large price in that day, and, as it furnished a means by which people in Virginia could make a living, it helped to make the colony successful. But in 1616 there were only three hundred and fifty English people in all North America.

A History of the United States and its People by Edward Eggleston

A History of the United States and its People by Edward Eggleston

The content outlines the early history of the United States, detailing exploration, settlement, colonial life, conflicts, and the events leading to the American Revolution.

CHAPTER

- How Columbus discovered America

- Other Discoveries in America

- Sir Walter Ralegh tries to settle a Colony in America

- How Jamestown was Settled

- The Starving Time, and what followed

- The Great Charter of Virginia

- The Coming of the Pilgrims

- The Coming of the Puritans

- The Coming of the Dutch

- The Settlement of Maryland and the Carolinas

- The Coming of the Quakers and Others to the Jerseys and Pennsylvania

- The Settlement of Georgia, and the Coming of the Germans, Irish, and French

- How the Indians Lived

- Early Indian Wars

- Traits of War with the Indians

- Life in the Colonial Time

- Farming and Shipping in the Colonies

- Bond-Servants and Slaves in the Colonies

- Laws and Usages in the Colonies

- The Spanish in Florida and the French in Canada

- Colonial Wars with France and Spain

- Braddock’s Defeat and the Expulsion of the Acadians

- Fall of Canada

- Characteristics of the Colonial Wars with the French

- How the Colonies were Governed

- Early Struggles for Liberty in the Colonies

- The Causes of the Revolution

- The Outbreak of the Revolution and Declaration of Independence

- The Battle of Trenton and the Capture of Burgoyne’s Army

- The Dark Period of the Revolution

- The Closing Years of the Revolution

The Coming of the Pilgrims

In the seventeenth century (that is, between the year 1600 and the year 1700) there was much religious persecution. In some countries the Catholics persecuted the Protestants, in other countries the Protestants persecuted the Catholics, and sometimes one kind of Protestants persecuted another. There were people in England who did not like the ceremonies of the Church of England, as established by law. These were called Puritans. Some of these went so far as to separate themselves from the Established Church and thus got the name of Separatists. They were persecuted in England, and many of them fled to Holland.

Among these were the members of a little Separatist congregation in Scrooby, in the north of England. Their pastor’s name was John Robinson. In 1607, the year in which Jamestown was settled, these persecuted people left England and settled in Holland, where they lived about thirteen years, most of the time in the city of Leyden [li’-den]. Then they thought they would like to plant a colony in America, where they could be religious in their own way. These are the people that we call “The Pilgrims,” on account of their wanderings for the sake of their religion.

About half of them were to go first. The rest went down to the sea to say farewell to those who were going. It was a sad parting, as they all knelt down on the shore and prayed together. The Pilgrims came to America in a ship called the Mayflower. There were about a hundred of them, and they had a stormy and wretched passage. They intended to go to the Hudson River, but their captain took them to Cape Cod. After exploring the coast north of that cape for some distance, they selected as a place to land a harbor which had been called Plymouth on the map prepared by Captain John Smith, who had sailed along this coast in an open boat in 1614.

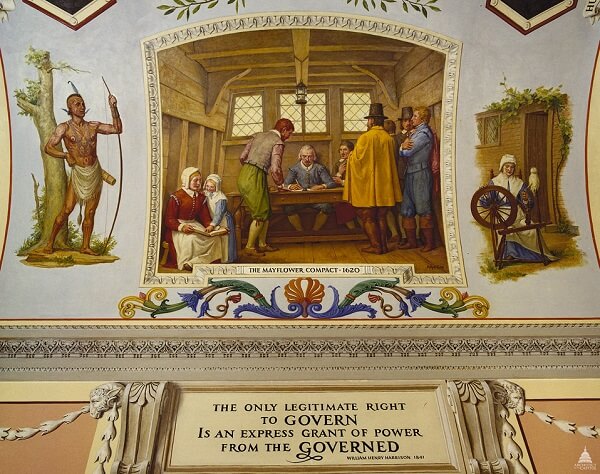

All the American Indians who had lived at this place had died a few years before of a pestilence, and the Pilgrims found the American Indian fields unoccupied. They first landed at this place on the nth day of December, 1620, as the days were then counted. This is the same as the 21st of December now, the mode of counting having changed since that time. (Through a mistake, the 22nd of December is generally kept in New England as “Forefathers’ Day.”) Before landing, the Pilgrims drew up an agreement by which they promised to be governed.

The bad voyage, the poor food with which they were provided, and a lack of good shelter in a climate colder than that from which they came, had their natural effect. Like the first settlers at Jamestown, they were soon nearly all sick. Forty-four out of the hundred Pilgrims died before the winter was ended, and by the time the first year was over half of them were dead. The Pilgrims were afraid of the American Indians, some of whom had attacked the first exploring party that had landed. To prevent the American Indians from finding out how much the party had been weakened by disease, they leveled all the graves, and planted Indian corn over the place in which the dead were buried. ‘The Mayflower Compact, 1620’ by the Architect of the Capitol

‘The Mayflower Compact, 1620’ by the Architect of the Capitol

One day, after the winter was over, an American Indian walked into the village and said in English, “Welcome, Englishmen.” He was a chief named Sam-o’-set, who had learned a little English from the fishermen on the coast of Maine. Samoset afterward brought with him an American Indian named Squanto, who had been carried away to England by a cruel captain many years before, and then brought back. Squanto remained with the Pilgrims, and taught them how to plant their corn as the American Indians did, by putting one or two fish into every hill for manure. He taught them many other things, and acted as their interpreter in their trading with the American Indians. He told the American Indians that they must keep peace with the settlers, who had the pestilence stored in their cellar along with the gunpowder. The neighboring chief, Mas-sa-so’-it, was also a good friend to the Pilgrims as long as he lived.

Captain Myles Standish was the military commander at Plymouth. He dealt severely with any American Indians supposed to be hostile. Finding that certain of the Massachusetts Indians were planning to kill all the settlers, he and some of his men seized the plotters suddenly and killed them with the knives which the American Indians wore suspended from their own necks.

The people of Plymouth suffered much from scarcity of food for several years. They had often nothing but oysters or clams to eat for a long time together, and no drink but water Like the Jamestown people, they tried a plan of living out of a common stock, but with no better success. In 1624 each family received a small allotment of land for its own, and from that time there was always plenty to eat in Plymouth. Others of the Pilgrims came to them from Holland, as well as a few emigrants from England. Plymouth Colony was, next to Virginia, the oldest colony of all, but it did not grow very fast, and in 1692, by a charter from King William III, it was united with Massachusetts, of which its territory still forms a part.

PILGRIMS AT HOME

The Pilgrims held their meetings in a square house on top of a hill at Plymouth. On the flat roof of this house were six small cannons. The people were called to church by the beating of a drum. The men carried loaded firearms with them when they went to meeting on Sunday, and put them where they could reach them easily. The town was surrounded by a stockade and had three gates. Elder Brewster was the religious teacher of the Pilgrims at Plymouth; their minister, John Robinson, having stayed with those who waited in Holland, and died there. It is said that Brewster, when he had nothing but shellfish and water for dinner, would cheerfully give thanks that they were “permitted to suck of the abundance of the seas and of the treasures hid in the sand.”

How Jamestown was Settled

After the total disappearance of Raleigh’s second colony, many years passed before another attempt was made. In 1602 Bartholomew Gosnold tried to plant a colony on the Island of Cuttyhunk, Massachusetts, in Buzzard’s Bay. If this had succeeded, New England would have been first settled, but the men that were to stay went back in the ship that brought them. In 1603 Queen Elizabeth died, and her cousin, James VI, King of Scotland, came to the throne of England as James I. In 1606, while Raleigh was shut up in the Tower of London, a company of merchants and others undertook to send a new colony to America. Some of the men who had been Raleigh’s partners in his last colony were members of this new “Virginia Company.”

It was in the stormy December of 1606 that the little colony set out. There were, of course, no steamships then; and the vessels they had were clumsy, small, and slow. The largest of the three ships that carried out the handful of people which began the settlement of the United States was named “Susan Constant.” She was of a hundred tons burden. Not many ships so small cross the ocean today. But the “Godspeed” which went along with her was not half so big, and the smallest of the three was a little pinnace of only twenty tons, called “Discovery.”

On account of storms, these feeble ships were not able to get out of sight of the English coast for six weeks. People in that time were afraid to sail straight across the unknown Atlantic Ocean; they went away south by the Canary Islands and the West Indies, and so made the distance twice as great as it ought to have been. It took the new colony about four months to get from London to Virginia. They intended to land on Roanoke Island, where Raleigh’s unfortunate colonies had been settled, but a storm drove them into a large river, which they called “James River,” in honor of the king. They arrived in Virginia in the month of April, when the banks of the river were covered with flowers. Great white dog-wood blossoms and masses of bright-colored red-bud were in bloom all along the James River. The newcomers said that heaven and earth had agreed together to make this a country to live in.

Replica Ship Susan Constant (In Front of Navy Vessel)

Replica Ship Susan Constant (In Front of Navy Vessel)

After sailing up and down the river they selected a place to live upon, which they called Jamestown.

They had now pretty well eaten up their supply of food, and they had been so slow in settling themselves that it was too late to plant even if they had cleared ground. One small ladleful of pottage made of worm-eaten barley or wheat was all that was given to a man for a meal. The settlers were attacked by the American Indians, who wounded seventeen men and killed one boy in the fight. Each man in Jamestown had to take his turn every third night in watching against the American Indians, lying on the cold, bare ground all night. The only water to drink was that from the river, which was bad. The people were soon nearly all of them sick; there were not five able-bodied men to defend the place had it been attacked. Sometimes as many as three or four died in a single night, and sometimes the living were hardly able to bury those who had died. There were about a hundred colonists landed at Jamestown, and one half of these died in the first few months. All this time the men in Jamestown were living in wretched tents and poor little hovels covered with earth, and some of them even in holes dug into the ground. As the sickness passed away, those who remained built themselves better cabins, and thatched the roofs with straw. Captain John Smith

Captain John Smith

One of the most industrious men in the colony at this time was Captain John Smith, a young man who had had many adventures, of which he was fond of boasting. He took the little pinnace “Discovery” and sailed up and down the rivers and bays of Virginia, exploring the country, getting acquainted with many tribes of American Indians, and exchanging beads, bells, and other trinkets for corn, with which he kept the Jamestown people from starving. In one of these trips two of his men were killed, and he was made captive, and led from tribe to tribe a prisoner. But he managed so well that Powhatan [povv-at-tan’], the head chief of about thirty tribes, set him free and sent him back to Jamestown. It was in this captivity that he made the acquaintance of Pocahontas [po-ka-hun’-tas], a daughter of Powhatan. She was then about ten years old, and Captain Smith greatly admired her. Many years afterward he told a pretty story about her putting her arms about her neck and saving his life when Powhatan wished to put him to death.

John Smith explored Chesapeake Bay in two voyages, enduring many hardships with cheerfulness. He and his men would move their fire two or three times in a cold night, that they might have the warm ground to lie upon. He managed the American Indians well, put down mutinies at Jamestown, and rendered many other services to the colony. He was the leading man in the new settlement, and came at length to be governor. But when many hundreds of new settlers were brought out under men who were his enemies, and Smith had been injured by an explosion of gunpowder, he gave up the government and went back to England.

CAPTAIN JOHN SMITH

Captain John Smith was born in England in 1579. While yet little more than a boy, he went into the wars in the Netherlands. He was afterward shipwrecked, robbed at sea, and suffered great want in France. He fought against the Turks and slew three of them in single combat. He was at length made prisoner by the Turks and reduced to slavery. By killing his master, he got free, escaping into Russia, after sixteen days of wandering. He got back to England and soon departed with the first company to Jamestown. After leaving Virginia he was the first to examine carefully the coast of New England, and he received the title of “Admiral of New England.” He was a bold and able explorer and a brave man, with much practical wisdom. His chief faults were his vanity and boastfulness, which led him to exaggerate his romantic adventures. But without him the Jamestown colony would probably have perished. Like many other worthy men, he died poor and neglected.

Sir Walter Raleigh Tries to Settle a Colony in America

Sir Walter Raleigh

Sir Walter Raleigh, while yet a young man, fought for years on the side of the Huguenots in the French civil wars, and afterward in the war in Ireland. On his return from Ireland, it is said that he won the Queen’s favor by throwing his new plush cloak into a muddy place in the road for her to walk on. He fitted out ships and fought against the Great Armada, or fleet, of Spain, when that country tried to conquer England. He was a great statesman, a great soldier, a great seaman, and an excellent poet and historian. He is said to have first planted the potato in Ireland. King James I kept him in prison in the Tower for more than twelve years, and then released him. In 1618 the same king had this great man put to death to please the King of Spain. When Raleigh was about to be beheaded, he felt of the edge of the axe, and said, “It is a sharp medicine to cure me of all my diseases.”

Sir Walter Raleigh was the first that landed a colony of English people on the land that is now the United States. Having received from Queen Elizabeth a charter which gave him a large territory in America, he sent out an exploring expedition in 1584, ninety-two years after the discovery by Columbus. This expedition was commanded by two captains, named Amidas and Barlowe. They landed on the coast in that part of America which we now call North Carolina. The country pleased them very much. They wondered at the wild grape-vines, which grew to the tops of the highest trees, and they found the American Indians very friendly. They stayed about six weeks in the New World, and, everything here being strange to their eyes, they fell into many mistakes in trying to describe what they saw and heard. When they got back to England, they declared that the part of America they had seen was the paradise of the world.

Raleigh was much encouraged by the accounts which his two captains gave of the new country they had found. It was named Virginia at this time, in honor of Queen Elizabeth, who was often called the “Virgin Queen.” But the name Virginia, which we apply to two of our states, was then used for nearly the whole eastern part of what is now the United States, between Maine and Georgia. Queen Elizabeth I of England

Queen Elizabeth I of England

In 1585, the year after the return of the first expedition, Raleigh sent out a colony to remain in America. Sir Richard Grenville, a famous seaman, had command of this expedition; but he soon returned to England, leaving the colony in charge of Ralph Lane. There were no women in Ralph Lane’s company. They made their settlement on Roanoke Island, which lies near to the coast of North Carolina, and they explored the mainland in many directions. They spent much time in trying to find gold, and they seem to have thought that the shell-beads worn by the American Indians were pearls. Like all the others who came to America in that time, they were very desirous of finding a way to get across America, which they believed to be very narrow. They hoped to reach the Pacific Ocean, and so open a new way of sailing: to China and the East Indies.

The American Indians by this time were tired of the settlers, and anxious to be rid of them. They told Lane that the Roanoke River came out of a rock so near to a sea at the west that the water sometimes dashed from the sea into the river, making the water of the river salt. Lane believed this story, and set out with most of his men to find a sea at the head of the river. Long before they got to the head of the Roanoke, their provisions gave out. But Lane made a brave speech to his men, and they resolved to go on. Having nothing else to eat, they killed their two dogs, and cooked the meat with sassafras leaves to give it a relish. When this meat was exhausted, they got into their boats and ran swiftly down the river, having no food to eat on the way home. Lane got back to Roanoke Island just in time to keep the American Indians from killing the men he had left there.

Sir Francis Drake came to see the colony on his return from an expedition to the West Indies. He furnished the company on the island with a ship and with whatever else they needed. But, while he remained at Roanoke, a storm arose which drove to sea the ship he had given to Lane. This so discouraged the colonists that they returned to England. Tobacco Field in South Carolina

Tobacco Field in South Carolina

Ralph Lane and his companions were the first to carry tobacco into England. They learned from the American Indians to smoke it by drawing the smoke into their mouths and puffing it out through their nostrils. Raleigh adopted the practice, and many distinguished men and women followed his example. Some of the first tobacco-pipes in England were made by using a walnut-shell for the bowl of the pipe and a straw for the stem. It is related that, when Raleigh’s servant first saw his master with the smoke coming from his nose, he thought him to be on fire, and poured a pitcher of ale, which he was fetching, over Sir Walter’s head, to put the fire out.

Raleigh set to work, with the help of others, to send out another colony. This time he sent women and children, as well as men, intending to make a permanent settlement. The governor of this company was John White, an artist. Soon after White’s company had settled themselves on Roanoke Island, an English child was born. This little girl, being the first English child born in Virginia, was named Virginia Dare.

John White, the governor of the colony, who was Virginia Dare’s grandfather went back to England for supplies. He was detained by the war with Spain, and, when he got back to Roanoke Island, the colony had disappeared Raleigh had spent so much money already that he was forced to give up the attempt’ to plant a colony in America. But he sent several times to seek for the lost people of his second colony, without finding them. Twenty years after John White left them, it was said that seven of them were still alive among the American Indians of North Carolina.