Sojourner Truth, born Isabella Baumfree around 1797, was an American abolitionist and advocate for African American civil rights, women’s rights, and temperance. She was born into slavery in Swartekill, New York, but escaped to freedom with her infant daughter in 1826. In 1828, she went to court to reclaim her son and became the first Black woman to win such a case against a white man. Truth passed away on November 26, 1883.

In 1843, she took the name Sojourner Truth after feeling called by God to leave the city and travel the countryside, “testifying to the hope that was in her.” Her most famous speech was given on the spot in 1851 at the Ohio Women’s Convention in Akron. During the Civil War, it became widely known as “Ain’t I a Woman?”, a reworked version of her speech published in 1863 in a stereotypical Black dialect common in the South at the time. In reality, Sojourner Truth’s first language was Dutch.

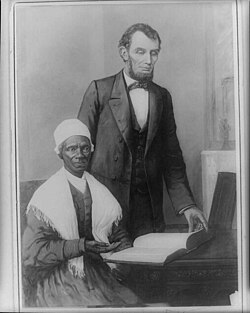

During the Civil War, Truth helped recruit Black men for the Union army. Afterward, she pushed for land grants from the federal government for formerly enslaved people, an effort tied to the promise of “forty acres and a mule,” but without success. She kept advocating for both women and African Americans until her death. As her biographer Nell Irvin Painter noted, “At a time when most Americans thought of slaves as male and women as white, Truth embodied a fact that still bears repeating: Among the Blacks are women; among the women, there are Blacks.”

Early years

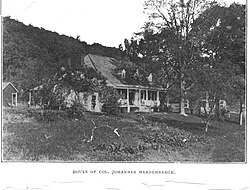

Sojourner Truth believed she was born sometime between 1797 and 1800. She was one of about a dozen children of James and Elizabeth Bomefree (later also spelled Baumfree). Her father, captured from what is now Ghana, was nicknamed “Bomefree” (which was thought to be Dutch for “tree”) for his tall height, while her mother, “Mau-Mau Bet,” was the daughter of enslaved people taken from the Guinea region. Colonel Hardenbergh purchased James and Elizabeth from slave traders and kept their family on his estate in a hilly area called Swartekill, just north of modern Rifton in Esopus, New York, about 95 miles north of New York City. As an infant, Truth’s five-year-old brother and three-year-old sister were sold to another estate. Her family often remembered those lost to slavery, and her mother taught her children to pray. Dutch was her first language, and she spoke with a Dutch accent throughout her life. After Hardenbergh’s death, his son Charles inherited the estate and continued to hold slaves there.

When Charles Hardenbergh died in 1806, nine-year-old Truth, known then as Belle, was sold at an auction along with a flock of sheep for $100 (~$2,010 in 2024) to John Neely near Kingston, New York. Until then, she spoke only Dutch, and when she learned English, it was with a Dutch accent rather than a stereotypical dialect. She later described Neely as cruel, recalling how he beat her daily, once even with a bundle of rods. In 1808, Neely sold her for $105 (~$2,067 in 2024) to tavern keeper Martinus Schryver of Port Ewen, New York, who kept her for 18 months before selling her in 1810 to John Dumont of West Park, New York.

Dumont repeatedly assaulted her, and there was significant tension between Truth and Dumont’s wife, Elizabeth Waring Dumont, who harassed her and made life harder. Around 1815, Truth met and fell in love with Robert, a slave from a nearby farm. His owner, Charles Catton Jr., a landscape painter, forbade the relationship because he didn’t want his slaves having children with people he didn’t own, as he wouldn’t own the children. One day, Robert sneaked over to see Truth, but when Catton and his son caught him, they brutally beat him until Dumont stepped in. Truth never saw Robert again, and he died a few years later, an event that haunted her for life. She later married an older enslaved man named Thomas, with whom she had five children: James, her firstborn who died young; Diana (1815), the child of John Dumont’s assault; and Peter (1821), Elizabeth (1825), and Sophia (c. 1826), all born after she and Thomas came together.

Freedom

In 1799, New York began passing laws to abolish slavery, though the process wasn’t finished until July 4, 1827. Dumont had promised to free Truth a year before the official emancipation if she “did well and was faithful.” But he went back on his word, saying a hand injury had made her less productive. Angry but determined, she kept working, spinning 100 pounds (45 kg) of wool to fulfill her sense of duty to him.

In late 1826, Truth gained her freedom, taking her infant daughter, Sophia, with her. Sadly, she had to leave her other children behind, as the emancipation order didn’t free them until they had worked as bound servants into their twenties. Reflecting on her escape, she said, “I didn’t run off, thinking that was wrong, but I walked away, believing it was the right thing to do.”

She eventually arrived at the home of Isaac and Maria Van Wagenen in New Paltz, where they welcomed her and her baby. Isaac offered to pay $20 for her services for the rest of the year, until the state’s emancipation took effect, and Dumont agreed. She stayed with them until the New York State Emancipation Act passed a year later.

When Truth found out that her five-year-old son Peter had been sold by Dumont and then illegally resold to someone in Alabama, she sought help from the Van Wagenens and took the matter to the New York Supreme Court. Using the name Isabella van Wagenen, she sued Peter’s new owner, Solomon Gedney. After months of legal battles in 1828, she regained custody of her son, who had suffered abuse. This made her one of the first Black women to win a court case against a white man. The lawsuit’s court documents were later rediscovered around 2022 by the staff at the New York State Archives.

In 1827, she converted to Christianity and helped establish the Methodist Church in Kingston, New York. Two years later, she moved to New York City and became a member of the John Street Methodist Church, also known as the Zion African Methodist Episcopal Church.

In 1833, she began working for Robert Matthews, known as the Prophet Matthias, who led a sect identifying with Judaism. She served as a housekeeper in their communal settlement and joined the group. In 1834, Matthews and Truth were accused of murdering Elijah Pierson but were acquitted due to lack of evidence, with Truth presenting letters that vouched for her reliability as a servant. The trial then shifted to allegations that Matthews had beaten his daughter, for which he was found guilty and sentenced to three months in jail plus thirty days for contempt of court. This led Truth to leave the sect in 1835, after which she lived in New York City until 1843.

In 1839, Truth’s son Peter joined the crew of a whaling ship called the Zone of Nantucket. Between 1840 and 1841, she got three letters from him, though in his third he mentioned sending five. Peter also said he hadn’t received any of her replies. When the ship came back to port in 1842, Peter wasn’t among the crew, and Truth never heard from him again.

The result of freedom

The year 1843 was a turning point for her. On June 1, Pentecost Sunday, she changed her name to Sojourner Truth. She chose the name because she heard the Spirit of God calling on her to preach the truth. She told her friends: “The Spirit calls me, and I must go”, and left to make her way traveling and preaching about the abolition of slavery. Taking along only a few possessions in a pillowcase, she traveled north, working her way up through the Connecticut River Valley, towards Massachusetts.

During that period, Truth started going to Millerite Adventist camp meetings. The Millerites, followers of William Miller from New York, believed Jesus would return in 1843–1844 to bring about the end of the world. Truth’s preaching and singing were well-loved in the community, and she often attracted large audiences. But when the predicted second coming didn’t happen, she, like many others, stepped back from her Millerite friends for a while.

In 1844, she became part of the Northampton Association of Education and Industry in Florence, Massachusetts. Founded by abolitionists, the group promoted women’s rights, religious tolerance, and pacifism. Over its four-and-a-half-year span, it had 240 members in total, but never more than 120 at once. Members lived on 470 acres, raising livestock and operating a sawmill, a gristmill, and a silk factory. Truth worked and lived there, managing the laundry and supervising both men and women. During her time in the community, she met William Lloyd Garrison, Frederick Douglass, and David Ruggles. Inspired by those around her, she gave her first anti-slavery speech that same year.

In 1845, she became part of George Benson’s household, who was William Lloyd Garrison’s brother-in-law. A year later, the Northampton Association of Education and Industry dissolved due to financial struggles. In 1849, she visited John Dumont before his move out west.

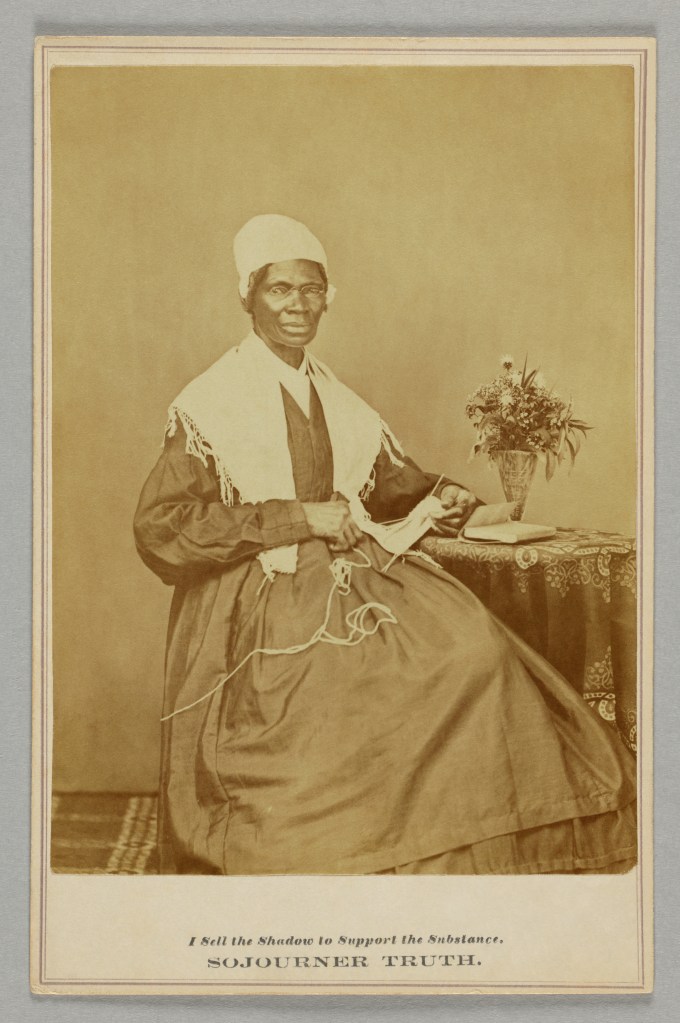

Truth began dictating her memoirs to her friend Olive Gilbert, and in 1850, William Lloyd Garrison privately published them as *The Narrative of Sojourner Truth: A Northern Slave*. That same year, she bought a home in Florence for $300 and spoke at the first National Women’s Rights Convention in Worcester, Massachusetts. In 1854, using proceeds from the book and cartes-de-visite captioned “I sell the shadow to support the substance,” she paid off the mortgage held by her friend and fellow community member, Samuel L. Hill.

“Ain’t I a Woman?”

In 1851, Truth teamed up with abolitionist and speaker George Thompson for a lecture tour across central and western New York. That May, she attended the Ohio Women’s Rights Convention in Akron, where she gave her now-famous impromptu speech, later called “Ain’t I a Woman?”. In it, she called for equal rights for all women, speaking from her experience as a former enslaved woman and blending the fight for abolition with women’s rights, using her strength as a laborer to support her case.

On a mission

Truth devoted her life to pushing for a fairer society for African Americans and women, championing causes like abolition, voting rights, and property rights. She was at the forefront of tackling overlapping social justice struggles. Historian Martha Jones noted that when Black women like Truth spoke about rights, they blended their ideas with challenges to slavery and racism. Truth shared her own experiences, hinting that the women’s movement could take a different path—one that stood for the broader interests of all humanity.

Illness and death

In her final years, Truth was cared for by two of her daughters. Just days before her death, a reporter from the Grand Rapids Eagle visited to interview her. Her face was thin and drawn, and she seemed to be in great pain. Still, her eyes shone brightly and her mind remained sharp, though speaking was difficult for her.

Truth passed away early in the morning on November 26, 1883, at her home in Battle Creek. Her funeral took place two days later at the Congregational-Presbyterian Church, led by Reverend Reed Stuart. Prominent citizens served as pallbearers, and nearly a thousand people attended the service. She was laid to rest in Oak Hill Cemetery.

In Washington, D.C., Frederick Douglass delivered a eulogy for her, praising her as venerable in age, insightful about human nature, remarkably independent and boldly self-assured, and deeply committed to the welfare of her race. For the past forty years, she had earned the respect and admiration of social reformers everywhere.

Comments on: "Sojourner Truth" (1)

[…] Sojourner Truth Martin Luther King, Jr. “I have a Dream Speech” Harriet Tubman: a Moses to her People The Legacy of Willard Saxby Townsend in Labor Rights ROSA LEE PARKS […]