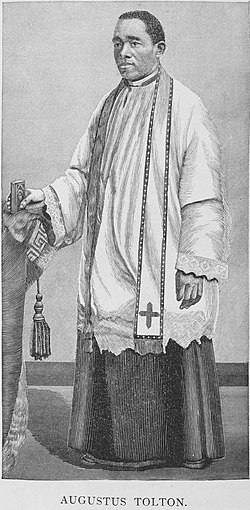

John Augustus Tolton, baptized Augustine, was born on April 1, 1854, and died on July 9, 1897. He was an African American Catholic and the first openly Black Catholic priest in the United States, ordained in Rome in 1886. Before him came the Healy brothers, Catholic priests who passed as White.

Born into slavery in Missouri, Tolton and his family escaped in 1863 and made a new home in Quincy, Illinois. Though highly educated, multilingual, and backed by supportive Irish- and German-American priests and Bishop Peter Joseph Baltes, who believed in his calling, he faced rejection from every major American seminary he applied to, as well as from the Mill Hill Missionaries in London. Undeterred, the bishop arranged for him to study at the Pontifical Urban University in Rome, where he was ordained in 1886. Initially expecting to serve in Africa, Tolton was instead reassigned by Cardinal Giovanni Simeoni to minister to African Americans in the United States.

Tolton began his ministry in the Diocese of Alton at his home parish in Quincy, facing strong resistance from both the German-American dean and local African-American Protestant ministers. Later, at his own request, he was reassigned to the Archdiocese of Chicago, where he played a key role in establishing St. Monica’s Church, an African-American “national parish” on the city’s South Side, marking a significant step for African-American Catholicism.

Thanks to the help of philanthropist Katharine Drexel, St. Monica’s was finished in 1893 at 36th and Dearborn Streets. Known affectionately as “Good Father Gus” by his parishioners, he passed away unexpectedly at age 43 from heatstroke during the 1897 Chicago heatwave. His cause for beatification was announced by Cardinal Francis George in 2010, and Pope Francis declared him venerable in June 2019.

Biography

Early

Parents and birth

Tolton was born into slavery and out of wedlock on April 1, 1854, in either Ralls County or Brush Creek, Missouri, to Martha Jane Chisley. He was baptized into the Catholic Church as “a slave child” owned by Stephen Elliott on May 29, 1854, at St. Peter’s Catholic Church in Rensselaer, near Hannibal, Missouri. His master’s daughter, Savilla Elliott, served as his godmother and taught her parents’ slaves Catholic religion classes. However, these lessons were limited to memorizing the Ten Commandments, which Martha Jane Chisley would often recite aloud during moments of deep emotion or fear, without fully understanding their meaning.

According to Joyce Duriga, in 1859—five years after Augustus was born—Martha Jane and a man named Peter Paul were given permission by their owners to marry. Peter Paul, a fellow slave, worked in the distillery on the neighboring Hagar plantation. Since several years had passed between Augustus’ birth and their marriage, it’s unlikely Peter was his biological father, though he was probably the only father Augustus ever knew. Later in life, Augustus never referred to Peter Paul as his father.

Freedom

The exact way the Tolton family gained their freedom is still debated. Descendants of the Elliott family claim that Stephen Elliott freed all his slaves at the start of the American Civil War and let them move North. However, the estate papers paint a very different picture.

In July 1863, Stephen Elliott, Tolton’s master, passed away, leaving his estate heavily in debt. His widow, Ann Elliott, had all their property appraised, including the enslaved individuals. Martha was valued at $59, her eldest son Charles at $100, her daughter Ann at $75, and her youngest son Augustus at $25.

Tolton’s stepfather, Peter Paul Hagar, was the first to escape from slavery. U.S. military records show that on September 20, 1863, he enlisted in the 3rd Arkansas Infantry Regiment of Colored Troops in Hannibal, Missouri, using the name “Peter Paul Lefevre,” a pseudonym inspired by the priest who had baptized him. He planned to fight for the Union Army in the Civil War, but sadly, he died of dysentery on January 12, 1864, in a military hospital in Helena, Arkansas.

The Elliott estate papers state that sometime between July and September 1863, Martha Jane Chisley and her children disappeared. In response, Ann Elliott hired slave catchers, giving a $10 down payment to capture the Chisley family under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. Later, in lectures and print, Augustus Tolton claimed that Ann Elliott offered a $600 bounty for the return of his entire family, dead or alive.

At the time, Union Army regiments stationed in Missouri and other border states were under strict orders not to interfere with slavery, provided slaveholders swore loyalty to the Union. However, the actions of the 38 “Liberators” from the 9th Minnesota Infantry Regiment—who, in November 1863, robbed a train in Otterville, Missouri to rescue the wife and children of a runaway slave from being sold out of state—show that Union soldiers often ignored these orders and openly defied them, even at the risk of court-martial.

After reaching Hannibal on foot, Martha and her children were shielded from arrest attempts by the local Union Army garrison. With a rowboat provided by Union soldiers, she managed to row her family one mile across the Mississippi River into the Free State of Illinois.

Education and seminary

After moving to the shanty town called “The Negro Quarter” in Quincy, Illinois, home to about 300 other Free Negroes, Martha, Augustus, and Charley started jobs at the Harris Tobacco Company, making cigars.

Martha enrolled her son in a segregated local public school named after Abraham Lincoln, where Tolton was placed in a class with much younger children and was reportedly bullied by older students. His first try at attending a Catholic school, St. Boniface downtown, faced racist resistance, leading him to withdraw within a month.

After Charley died at age ten, Augustine met Peter McGirr, a Catholic priest from Fintona, County Tyrone, who had grown up in a nearby Irish-American farming community. McGirr took Tolton under his wing and arranged for him to attend St. Lawrence’s (later St. Peter’s) Catholic School during the winter months when the tobacco factory was closed. The decision stirred controversy in the parish. While the priests and nuns treated Tolton kindly, many parishioners objected to a Black student attending school with their children. McGirr stood firm, allowing Tolton to continue his studies. Tolton received his First Communion and confirmation from Bishop Peter Joseph Baltes of the Diocese of Alton at St. Peter’s Church on June 12, 1870, around the time the Chisley family first appeared in records using their new surname, Tolton. Although runaway slaves often adopted new surnames to avoid recapture, the reason they chose “Tolton” remains a mystery. Augustus Tolton graduated from St. Peter’s School in 1872.

In 1874, a 20-year-old Tolton joined two local German-American priests in starting a tuition-free Catholic school for the children of Quincy’s Black community. The school quickly became so popular that the School Sisters of Notre Dame sent a nun and a postulant from Milwaukee to help teach. One Sister noted, “The older pupils studied the Catechism so diligently that the Holy Sacraments could be administered to them—surely the new school’s sweetest and most beneficial fruit.”

Although African-American Baptist and Methodist ministers protested after seven students were baptized into the Catholic Church in the first year—eventually succeeding by 1880 in pressuring the Diocese to close the school—Tolton always looked back on this period with fondness. He later wrote, “I was a poor slave boy, but the priests of the Church did not disdain me… It was through one of them that I stand before you today… and through the guidance of a Sister of Notre Dame, Sister Herlinda, I learned to interpret the Ten Commandments. That was when I first saw the glimmering light of truth and the majesty of the Church.”

In 1875, Tolton briefly returned to his native Missouri, then rid of slavery after the Civil War.

While teaching at a Catholic school for fellow African Americans, Tolton was admitted to St. Francis Solanus College (now Quincy University), where he studied from 1878 to 1880. There’s no surviving evidence that he had to pay tuition. Initially, some White students from Missouri threatened to leave if Tolton remained, but the Franciscan Order made it clear the Church would not discriminate based on race and that those students were free to go if they chose. In 1880, Tolton graduated as his class valedictorian.

The Chicago Journal of History recounts that Bishop Balthes told Peter McGirr, “Find a seminary that will accept a Black candidate. The Diocese will cover the cost.” In letters to various seminaries, Bishop Balthes often described Tolton as “more than ordinary.”

Despite the best efforts of the bishop and McGirr, Augustus Tolton was turned down by every American seminary he applied to. In the meantime, diocesan priests kept tutoring him in Ecclesiastical Latin, Koine Greek, German, history both ancient and modern, philosophy, and geography.

In a letter to the Mill Hill Missionaries, a religious order founded by Cardinal Herbert Vaughan to serve the Black population of the British Empire from their headquarters in Mill Hill, North London, Theodore Wegmann, assistant pastor of St. Boniface Church in Quincy, wrote, “I am writing on behalf of a young man of African descent who is eager to become a missionary for his people. I have been instructing him for about a year and a half at the request of his pastor, Reverend Peter McGirr of St. Peter’s Church here. He is around 20 years old, of excellent character, and gifted with good talents. Having studied Latin for over a year, he can read Nepos and Caesar, and recently I began teaching him Greek. I am happy to continue guiding his studies if there is hope for him to achieve his goal of entering the sacred priesthood, provided there is a college willing to admit him when the time comes.”

The Mill Hill Missionaries, whose American branch would later be called the Josephites, turned down Wegmann’s request and refused to accept Augustus Tolton. Reflecting on the order’s later missionary work among African Americans across the United States, Joyce Duriga noted that Tolton’s bid for seminary admission was simply about a decade ahead of its time.

Determined not to give up, the Franciscans at St. Francis Solanus College managed to arrange for Tolton to study at the Pontifical Urban University in Rome.

On February 21, 1880, Tolton boarded the ship Der Westlicher, sailing from Hoboken, New Jersey, to Le Havre in the Third French Republic. He reached Rome on March 10, 1880, and reported to the Pontifical Urban University, where, by March 12, he had become as fluent in Italian as he already was in Ecclesiastical Latin, German, and Greek.

Priesthood

Tolton was ordained as a priest in Rome on April 24, 1886, at the age of 31, in the Archbasilica of Saint John Lateran. He celebrated his first public Mass at St. Peter’s Basilica on Easter Sunday that same year. Planning to work as a missionary during the Scramble for Africa, he had studied the regional cultures and languages of his ancestral continent in detail.

Tolton’s plans hit an unexpected snag in the form of Cardinal Giovanni Simeoni, Prefect of the Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith. Back in November 1883, Simeoni, who headed the Catholic Church’s global missionary efforts, had called all U.S. bishops—since the country was still considered mission territory—to Rome. During their meeting, he presented a list of twelve issues for the American bishops to address. Notably, he pointed out that little progress had been made for emancipated slaves since the last Council and suggested a special parish collection to support missions serving Black communities in America.

When the newly ordained Tolton was sent back to the United States to serve as a Catholic missionary to the Black community, Cardinal Simeoni remarked, as he issued the order in a document still preserved in the Vatican archives, “America has been called the most enlightened nation. We’ll see if it deserves the honor. If America has never seen a Black priest, it will see one now.”

Tolton celebrated his first Mass in the United States at St. Mary’s Hospital in Hoboken, New Jersey, on July 7, 1886. A few days later, on July 11, 1886, he led a Solemn High Mass at St. Benedict the Moor Catholic Church in Hell’s Kitchen, Manhattan, New York City.

He held his first Mass in Quincy on July 18, 1886, at St. Boniface. Over time, he tried to establish a parish there but faced pushback from White ethnic Catholics, many of them German-Americans, and even stronger resistance from African American Protestant ministers worried about losing members to Catholicism. He went on to form St. Joseph Catholic Church and school in Quincy, but clashed with the new parish dean, who insisted on turning away white worshipers from his Masses.

After being reassigned to Chicago, Tolton took charge of St. Augustine’s mission society, which met in the basement of St. Mary’s Church. He also oversaw the creation and management of St. Monica’s Catholic Church, the Negro “national parish” located at 36th and Dearborn Streets on the South Side. The church’s nave could seat 850 people and was funded by generous contributions from philanthropists Mrs. Anne O’Neill and Katharine Drexel.

St. Monica’s Parish expanded from just 30 parishioners to 600 after the new church was built. Tolton’s remarkable work with Black Catholics soon gained him national recognition within the Catholic hierarchy. Affectionately nicknamed “Good Father Gus,” he was celebrated for his eloquent sermons, beautiful singing voice, and skillful accordion playing.

Several news articles from the time highlight his character and significance. In 1893, the Lewiston Daily Sun wrote, while he was working to establish St. Monica’s for African American Catholics in Chicago, “Father Tolton is a fluent, graceful speaker with a remarkably sweet singing voice, which shines in the chants of high mass. It’s not uncommon to see many white people among his congregation.”

In Chicago, Tolton was warmly received by the Jesuits of Holy Family Church and St. Ignatius College (now St. Ignatius College Prep). They welcomed him into the Jesuit residence in the old 1869 school building and invited him to preach at High Mass on January 29, 1893. At the time, Holy Family was the largest English-speaking parish in the city, made up mostly of South Side Irish who were also working to find their place in a sometimes unwelcoming Chicago. Tolton spoke at all the masses and raised $500 (about $14,000 in 2020) for St. Monica Church, which was dedicated on January 14, 1894. In 1894, The True Witness and Catholic Chronicle called him “indefatigable” in his mission to build the new parish.

Daniel Rudd, who organized the first Colored Catholic Congress in 1889, was quoted in the November 8, 1888 edition of The Irish Canadian, sharing his thoughts about the upcoming event by saying:

- “For a long time the idea prevailed that the negro was not wanted beyond the altar rail, and for that reason, no doubt, hundreds of young colored men who would otherwise be officiating at the altar rail today have entered other walks. Now that this mistaken idea has been dispelled by the advent of one full-blooded negro priest, the Rev. Augustus Tolton, many more have entered the seminaries in this country and Europe.”

Tolton would go on to say Mass at the Congress itself, held in Washington, D.C.

A few months later, Tolton’s significance within parts of the American Catholic hierarchy was evident when he took part in an international celebration marking 100 years since the establishment of the first Catholic Diocese in the United States. As reported in the New York Times on November 11, 1889, when Cardinal Gibbons stepped back to his seat on the altar, reporters in the makeshift press gallery noticed, just a few feet away among abbots and other dignitaries, the face of Father Tolton of Chicago — the first African American Catholic priest ordained in America.

Death

In 1893, Tolton began experiencing frequent bouts of illness, which eventually led him to take a temporary leave from his duties at St. Monica’s Parish in 1895.

At 43, on July 8, 1897, he collapsed and passed away the next day at Mercy Hospital due to the Chicago heat wave. After a funeral attended by 100 priests, Tolton was laid to rest in the priests’ lot at St. Peter’s Cemetery in Quincy, honoring his wish.

After Tolton’s death, St. Monica’s was made a mission of St. Elizabeth’s Church. In 1924 it was closed as a national parish, as Black Catholics chose to attend parish churches in their neighborhoods.

Cause for beatification and canonization

On March 1, 2010, Cardinal Francis George of Chicago announced the start of an official investigation into Tolton’s life and virtues, aiming to open the cause for his canonization. The effort is also being supported by the Diocese of Springfield in Illinois, where Tolton first served as a priest, and the Diocese of Jefferson City, where his family had been enslaved.

On February 24, 2011, the cause for Tolton’s sainthood was officially introduced, granting him the title of Servant of God. Historical and theological commissions were set up to study his life, alongside the Father Tolton Guild, which works to promote his cause through spiritual and financial support. Cardinal George appointed Joseph Perry, Auxiliary Bishop of Chicago, as the diocesan postulator for Tolton’s canonization.

On September 29, 2014, Cardinal George officially ended the investigation into Tolton’s life and virtues. The research collected was sent to the Vatican, where it was reviewed, compiled into a book called a “positio” or official position paper, studied by theologians, and then presented to the pope. If it’s determined that Tolton lived a life of heroic virtue, the next step would be to declare him “Venerable.”

On December 10, 2016, Tolton’s remains were exhumed and confirmed as part of the canonization process. Following canon law procedures, a forensic pathologist verified the remains—which included a skull, femurs, ribs, vertebrae, pelvis, and parts of arm bones—were indeed his. Also discovered were the corpus from a crucifix, a piece of a Roman collar, the corpus from his rosary, and glass shards suggesting the coffin once had a glass top. After verification, the remains were dressed in a new chasuble and reburied.

On March 8, 2018, historians working with the Congregation for the Causes of Saints unanimously agreed to advance Tolton’s cause after reviewing and approving the positio. Then, on February 5, 2019, the nine-member theological commission also gave unanimous approval. From there, it went to the cardinal and bishop members of the Congregation for their consent before being sent to the pope for final confirmation.

On June 12, 2019, Pope Francis approved the Decree of Heroic Virtue, moving Tolton’s cause forward. This recognition granted Tolton the title of Venerable. If the process continues, the next steps will be beatification and then canonization.

Comments on: "Augustus Tolton: First Black Catholic Priest in America" (1)

[…] Augustus Tolton: First Black Catholic Priest in America Father Cyprian Davis: A Historian of Hope and a Witness to Black Catholic Faith {Coming soon} The Life and Legacy of Sister Thea Bowman Mother Mary Lange: A Pioneer of Faith, Education, and Courage {Coming soon} […]