Chapter 2: The Open Road

Ratty,’ said the Mole suddenly, one bright summer morning, ‘if you please, I want to ask you a favour.’

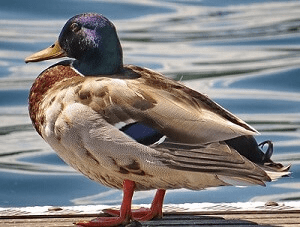

The Rat was sitting on the river bank, singing a little song. He had just composed it himself, so he was very taken up with it, and would not pay proper attention to Mole or anything else. Since early morning he had been swimming in the river, in company with his friends the ducks. And when the ducks stood on their heads suddenly, as ducks will, he would dive down and tickle their necks, just under where their chins would be if ducks had chins, till they were forced to come to the surface again in a hurry, spluttering and angry and shaking their feathers at him, for it is impossible to say quite ALL you feel when your head is under water. At last they implored him to go away and attend to his own affairs and leave them to mind theirs. So the Rat went away, and sat on the river bank in the sun, and made up a song about them, which he called

‘THE DUCKS’ DITTY.’

All along the backwater,

Through the rushes tall,

Ducks are a-dabbling,

Up tails all!

Ducks’ tails, drakes’ tails,

Yellow feet a-quiver,

Yellow beaks all out of sight

Busy in the river!

Slushy green undergrowth

Where the roach swim-

Here we keep our larder,

Cool and full and dim.

Everyone for what he likes!

We like to be

Heads down, tails up,

Dabbling free!

High in the blue above

Swifts whirl and call-

We are down a-dabbling

Uptails all!

‘I don’t know that I think so VERY much of that little song, Rat,’ observed the Mole cautiously. He was no poet himself and didn’t care who knew it; and he had a candid nature.

‘Nor don’t the ducks neither,’ replied the Rat cheerfully. ‘They say, “WHY can’t fellows be allowed to do what they like WHEN they like and AS they like, instead of other fellows sitting on banks and watching them all the time and making remarks and poetry and things about them? What NONSENSE it all is!” That’s what the ducks say.’

‘So it is, so it is,’ said the Mole, with great heartiness.

‘No, it isn’t!’ cried the Rat indignantly.

‘Well then, it isn’t, it isn’t,’ replied the Mole soothingly. ‘But what I wanted to ask you was, wouldn’t you take me to call on Mr. Toad? I’ve heard so much about him, and I do so want to make his acquaintance.’

‘Why, certainly,’ said the good-natured Rat, jumping to his feet and dismissing poetry from his mind for the day. ‘Get the boat out, and we’ll paddle up there at once. It’s never the wrong time to call on Toad. Early or late he’s always the same fellow. Always good-tempered, always glad to see you, always sorry when you go!’

‘He must be a very nice animal,’ observed the Mole, as he got into the boat and took the sculls, while the Rat settled himself comfortably in the stern.

‘He is indeed the best of animals,’ replied the Rat. ‘So simple, and so good-natured, and so affectionate. Perhaps he’s not very clever-we can’t all be geniuses; and it may be that he is both boastful and conceited. But he has got some very great qualities, has Toady.’

Rounding a bend in the river, they came in sight of a handsome, dignified old house of mellowed red brick, with well-kept lawns reaching down to the water’s edge.

‘That’s Toad Hall,’ said the Rat; ‘and that creek on the left, where the notice-board says, “Private. No landing allowed,” leads to his boat-house, where we’ll leave the boat. The stables are over there to the right. That’s the banqueting-hall you’re looking at now-very old, it is. Toad is rather rich, you know, and this is really one of the nicest houses in these parts, though we never admit as much to Toad.’

They glided up the creek, and the Mole shipped his sculls as they passed into the shadow of a large boat-house. Here they saw many handsome boats, slung from the cross beams or hauled up on a slip, but none in the water; and the place had an unused and a deserted air.

The Rat looked around him. ‘I understand,’ said he. ‘Boating is played out. He’s tired of it, and done with it. I wonder what new fad he has taken up now? Come along, let’s look him up. We shall hear all about it quite soon enough.’

They disembarked, and strolled across the gay flower-decked lawns in search of Toad, whom they presently happened upon resting in a wicker garden-chair, with a pre-occupied expression of face, and a large map spread out on his knees.

‘Hooray!’ he cried, jumping up on seeing them both, ‘this is splendid!’ He shook the paws of both of them warmly, never waiting for an introduction to the Mole. ‘How KIND of you!’ he went on, dancing round them. ‘I was just going to send a boat down the river for you, Ratty, with strict orders that you were to be fetched up here at once, whatever you were doing. I want to see you badly-both of you. Now what will you take? Come inside and have something! You don’t know how lucky it is, your turning up just now!’

‘Let’s just sit quiet a bit, Toady!’ said the Rat, throwing himself into an easy chair, while the Mole took another by the side of him and made some civil remark about the Toad’s ‘delightful residence.’

‘Finest house on the whole river,’ cried Toad boisterously. ‘Or anywhere else, for that matter,’ he could not help adding.

Here the Rat nudged the Mole. Unfortunately the Toad saw him do it, and turned very red. There was a moment’s painful silence. Then Toad burst out laughing. ‘All right, Ratty,’ he said. ‘It’s only my way, you know. And it’s not such a very bad house, is it? You know you rather like it yourself. Now, look here. Let’s be sensible. You are the very animals I wanted. You’ve got to help me. It’s most important!’

‘It’s about your rowing, I suppose,’ said the Rat, with an innocent air. ‘You’re getting on fairly well, though you splash a good bit still. With a great deal of patience, and any quantity of coaching, you may–‘

‘O, pooh! boating!’ interrupted the Toad, in great disgust. ‘Silly boyish amusement. I’ve given that up LONG ago. Sheer waste of time, that’s what it is. It makes me downright sorry to see you fellows, who ought to know better, spending all your energies in that aimless manner. No, I’ve discovered the real thing, the only genuine occupation for a life time. I propose to devote the remainder of mine to it, and can only regret the wasted years that lie behind me, squandered in trivialities. Come with me, my dear Ratty, and your amiable friend also, if he will be so very good, just as far as the stable-yard, and you shall see what you shall see!’

He led the way to the stable-yard accordingly, the Rat following with a most mistrustful expression; and there, drawn out of the coach house into the open, they saw a gypsy caravan, shining with newness, painted a canary-yellow picked out with green, and red wheels.

‘There you are!’ cried the Toad, straddling and expanding himself. ‘There’s real life for you, embodied in that little cart. The open road, the dusty highway, the heath, the common, the hedgerows, the rolling downs! Camps, villages, towns, cities! Here today, up and off to somewhere else tomorrow! Travel, change, interest, excitement! The whole world before you, and a horizon that’s always changing! And mind! this is the very finest cart of its sort that was ever built, without any exception. Come inside and look at the arrangements. Planned ’em all myself, I did!’

The Mole was tremendously interested and excited, and followed him eagerly up the steps and into the interior of the caravan. The Rat only snorted and thrust his hands deep into his pockets, remaining where he was.

It was indeed very compact and comfortable. Little sleeping bunks-a little table that folded up against the wall-a cooking-stove, lockers, bookshelves, a bird-cage with a bird in it; and pots, pans, jugs and kettles of every size and variety.

‘All complete!’ said the Toad triumphantly, pulling open a locker. ‘You see-biscuits, potted lobster, sardines-everything you can possibly want. Soda-water here-baccy there-letter-paper, bacon, jam, cards and dominoes-you’ll find,’ he continued, as they descended the steps again, ‘you’ll find that nothing whatsoever has been forgotten, when we make our start this afternoon.’

‘I beg your pardon,’ said the Rat slowly, as he chewed a straw, ‘but did I overhear you say something about “WE,” and “START,” and “THIS AFTERNOON?”‘

‘Now, you dear good old Ratty,’ said Toad, imploringly, ‘don’t begin talking in that stiff and sniffy sort of way, because you know you’ve GOT to come. I can’t possibly manage without you, so please consider it settled, and don’t argue-it’s the one thing I can’t stand. You surely don’t mean to stick to your dull fusty old river all your life, and just live in a hole in a bank, and BOAT? I want to show you the world! I’m going to make an ANIMAL of you, my boy!’

‘I don’t care,’ said the Rat, doggedly. ‘I’m not coming, and that’s flat. And I AM going to stick to my old river, AND live in a hole, AND boat, as I’ve always done. And what’s more, Mole’s going to stick to me and do as I do, aren’t you, Mole?’

‘Of course I am,’ said the Mole, loyally. ‘I’ll always stick to you, Rat, and what you say is to be-has got to be. All the same, it sounds as if it might have been-well, rather fun, you know!’ he added, wistfully. Poor Mole! The Life Adventurous was so new a thing to him, and so thrilling; and this fresh aspect of it was so tempting; and he had fallen in love at first sight with the canary-colored cart and all its little fitments.

The Rat saw what was passing in his mind, and wavered. He hated disappointing people, and he was fond of the Mole, and would do almost anything to oblige him. Toad was watching both of them closely.

‘Come along in, and have some lunch,’ he said, diplomatically, ‘and we’ll talk it over. We needn’t decide anything in a hurry. Of course, I don’t really care. I only want to give pleasure to you fellows. “Live for others!” That’s my motto in life.’

During luncheon-which was excellent, of course, as everything at Toad Hall always was-the Toad simply let himself go. Disregarding the Rat, he proceeded to play upon the inexperienced Mole as on a harp. Naturally a voluble animal, and always mastered by his imagination, he painted the prospects of the trip and the joys of the open life and the roadside in such glowing colors that the Mole could hardly sit in his chair for excitement. Somehow, it soon seemed taken for granted by all three of them that the trip was a settled thing; and the Rat, though still unconvinced in his mind, allowed his good-nature to over-ride his personal objections. He could not bear to disappoint his two friends, who were already deep in schemes and anticipations, planning out each day’s separate occupation for several weeks ahead.

When they were quite ready, the now triumphant Toad led his companions to the paddock and set them to capture the old grey horse, who, without having been consulted, and to his own extreme annoyance, had been told off by Toad for the dustiest job in this dusty expedition. He frankly preferred the paddock, and took a deal of catching. Meantime Toad packed the lockers still tighter with necessaries, and hung nosebags, nets of onions, bundles of hay, and baskets from the bottom of the cart. At last the horse was caught and harnessed, and they set off, all talking at once, each animal either trudging by the side of the cart or sitting on the shaft, as the humor took him. It was a golden afternoon. The smell of the dust they kicked up was rich and satisfying; out of thick orchards on either side the road, birds called and whistled to them cheerily; good-natured wayfarers, passing them, gave them ‘Good-day,’ or stopped to say nice things about their beautiful cart; and rabbits, sitting at their front doors in the hedgerows, held up their fore-paws, and said, ‘O my! O my! O my!’

Late in the evening, tired and happy and miles from home, they drew up on a remote common far from habitations, turned the horse loose to graze, and ate their simple supper sitting on the grass by the side of the cart. Toad talked big about all he was going to do in the days to come, while stars grew fuller and larger all around them, and a yellow moon, appearing suddenly and silently from nowhere in particular, came to keep them company and listen to their talk. At last they turned in to their little bunks in the cart; and Toad, kicking out his legs, sleepily said, ‘Well, good night, you fellows! This is the real life for a gentleman! Talk about your old river!’

‘I DON’T talk about my river,’ replied the patient Rat. ‘You KNOW I don’t, Toad. But I THINK about it,’ he added rather pathetically, in a lower tone: ‘I think about it-all the time!’

The Mole reached out from under his blanket, felt for the Rat’s paw in the darkness, and gave it a squeeze. ‘I’ll do whatever you like, Ratty,’ he whispered. ‘Shall we run away tomorrow morning, quite early-VERY early-and go back to our dear old hole on the river?’

‘No, no, we’ll see it out,’ whispered back the Rat. ‘Thanks awfully, but I ought to stick by Toad till this trip is ended. It wouldn’t be safe for him to be left to himself. It won’t take very long. His fads never do. Now good night!’

The end was indeed nearer than even the Rat suspected.

After so much open air and excitement the Toad slept very soundly, and no amount of shaking could rouse him out of bed the next morning. So the Mole and Rat turned to, quietly and manfully, and while the Rat saw to the horse, and lit a fire, and cleaned up last night’s cups and platters, and got things ready for breakfast, the Mole trudged off to the nearest village, a long way off, for milk and eggs and various necessaries the Toad had, of course, forgotten to provide. The hard work had all been done, and the two animals were resting, thoroughly exhausted, by the time Toad appeared on the scene, fresh and gay, remarking what a pleasant easy life it was they were all leading now, after the cares and worries and fatigues of housekeeping at home.

They had a pleasant ramble that day over grassy downs and along narrow by-lanes, and camped as before, on a common, only this time the two guests took care that Toad should do his fair share of work. In consequence, when the time came for starting next morning, Toad was by no means so rapturous about the simplicity of the primitive life, and indeed attempted to resume his place in his bunk, whence he was hauled by force. Their way lay, as before, across country by narrow lanes, and it was not till the afternoon that they came out on the high-road, their first high-road; and there disaster, fleet and unforeseen, sprang upon them-disaster momentous indeed to their expedition, but simply overwhelming in its effect on the after-career of Toad.

They were strolling along the high-road easily, the Mole by the horse’s head, talking to him, since the horse had complained that he was being frightfully left out of it all, and no one considered him in the least; the Toad and the Water Rat walking behind the cart talking together-at least Toad was talking, and Rat was saying at intervals, ‘Oh yes, precisely; and what did YOU say to HIM?’-and thinking all the time of something very different, when far behind them they heard a faint warning hum; like the drone of a distant bee. Glancing back, they saw a small cloud of dust, with a dark center of energy, advancing on them at incredible speed, while from out the dust a faint ‘Poop-poop!’ wailed like an uneasy animal in pain. Hardly regarding it, they turned to resume their conversation, when in an instant (as it seemed) the peaceful scene was changed, and with a blast of air and a whirl of sound that made them jump for the nearest ditch, It was on them! The ‘Poop-poop’ rang with a brazen shout in their ears, they had a moment’s glimpse of an interior of glittering plate-glass and rich morocco, and the magnificent motorcar, immense, breath-snatching, passionate, with its pilot tense and hugging his wheel, possessed all earth and air for the fraction of a second, flung an enveloping cloud of dust that blinded and enwrapped them utterly, and then dwindled to a speck in the far distance, changed back into a droning bee once more.

The old grey horse, dreaming, as he plodded along, of his quiet paddock, in a new raw situation such as this simply abandoned himself to his natural emotions. Rearing, plunging, backing steadily, in spite of all the Mole’s efforts at his head, and all the Mole’s lively language directed at his better feelings, he drove the cart backwards towards the deep ditch at the side of the road. It wavered an instant-then there was a heartrending crash-and the canary-colored cart, their pride and joy, lay on its side in the ditch, an irredeemable wreck.

The Rat danced up and down in the road, simply transported with passion. ‘You villains!’ he shouted, shaking both fists, ‘You scoundrels, you highwaymen, you-you-roadhogs!-I’ll have the law of you! I’ll report you! I’ll take you through all the Courts!’ His home-sickness had quite slipped away from him, and for the moment he was the skipper of the canary-colored vessel driven on a shoal by the reckless jockeying of rival mariners, and he was trying to recollect all the fine and biting things he used to say to masters of steam-launches when their wash, as they drove too near the bank, used to flood his parlor-carpet at home.

Toad sat straight down in the middle of the dusty road, his legs stretched out before him, and stared fixedly in the direction of the disappearing motorcar. He breathed short, his face wore a placid satisfied expression, and at intervals he faintly murmured ‘Poop-poop!’

The Mole was busy trying to quiet the horse, which he succeeded in doing after a time. Then he went to look at the cart, on its side in the ditch. It was indeed a sorry sight. Panels and windows smashed, the axles hopelessly bent, one wheel off, sardine-tins scattered over the wide world, and the bird in the bird-cage sobbing pitifully and calling to be let out.

The Rat came to help him, but their united efforts were not sufficient to right the cart. ‘Hi! Toad!’ they cried. ‘Come and bear a hand, can’t you!’

The Toad never answered a word, or budged from his seat in the road; so they went to see what was the matter with him. They found him in a sort of a trance, a happy smile on his face, his eyes still fixed on the dusty wake of their destroyer. At intervals he was still heard to murmur ‘Poop-poop!’

The Rat shook him by the shoulder. ‘Are you coming to help us, Toad?’ he demanded sternly.

‘Glorious, stirring sight!’ murmured Toad, never offering to move. ‘The poetry of motion! The REAL way to travel! The ONLY way to travel! Here today-in next week tomorrow! Villages skipped, towns and cities jumped-always someone else’s horizon! O bliss! O poop-poop! O my! O my!’

‘O STOP being an ass, Toad!’ cried the Mole despairingly.

‘And to think I never KNEW!’ went on the Toad in a dreamy monotone. ‘All those wasted years that lie behind me, I never knew, never even DREAMT! But NOW-but now that I know, now that I fully realise! O what a flowery track lies spread before me, henceforth! What dusty-clouds shall spring up behind me as I speed on my reckless way! What carts I shall fling carelessly into the ditch in the wake of my magnificent onset! Horrid little carts-common carts-canary-colored carts!’

‘What are we to do with him?’ asked the Mole of the Water Rat.

‘Nothing at all,’ replied the Rat firmly. ‘Because there is really nothing to be done. You see, I know him from of old. He is now possessed. He has got a new craze, and it always takes him that way, in its first stage. He’ll continue like that for days now, like an animal walking in a happy dream, quite useless for all practical purposes. Never mind him. Let’s go and see what there is to be done about the cart.’

A careful inspection showed them that, even if they succeeded in righting it by themselves, the cart would travel no longer. The axles were in a hopeless state, and the missing wheel was shattered into pieces.

The Rat knotted the horse’s reins over his back and took him by the head, carrying the bird cage and its hysterical occupant in the other hand. ‘Come on!’ he said grimly to the Mole. ‘It’s five or six miles to the nearest town, and we shall have to walk it. The sooner we make a start the better.’

‘But what about Toad?’ asked the Mole anxiously, as they set off together. ‘We can’t leave him here, sitting in the middle of the road by himself, in the distracted state he’s in! It’s not safe. Supposing another Thing were to come along?’

‘O, BOTHER Toad,’ said the Rat savagely; ‘I’ve done with him!’

They had not proceeded very far on their way, however, when there was a pattering of feet behind them, and Toad caught them up and thrust a paw inside the elbow of each of them; still breathing short and staring into vacancy.

‘Now, look here, Toad!’ said the Rat sharply: ‘as soon as we get to the town, you’ll have to go straight to the police-station, and see if they know anything about that motorcar and who it belongs to, and lodge a complaint against it. And then you’ll have to go to a blacksmith’s or a wheelwright’s and arrange for the cart to be fetched and mended and put to rights. It’ll take time, but it’s not quite a hopeless smash. Meanwhile, the Mole and I will go to an inn and find comfortable rooms where we can stay till the cart’s ready, and till your nerves have recovered their shock.’

‘Police-station! Complaint!’ murmured Toad dreamily. ‘Me COMPLAIN of that beautiful, that heavenly vision that has been vouchsafed me! MEND THE CART! I’ve done with carts forever. I never want to see the cart, or to hear of it, again. O, Ratty! You can’t think how obliged I am to you for consenting to come on this trip! I wouldn’t have gone without you, and then I might never have seen that-that swan, that sunbeam, that thunderbolt! I might never have heard that entrancing sound, or smelt that bewitching smell! I owe it all to you, my best of friends!’

The Rat turned from him in despair. ‘You see what it is?’ he said to the Mole, addressing him across Toad’s head: ‘He’s quite hopeless. I give it up-when we get to the town we’ll go to the railway station, and with luck we may pick up a train there that’ll get us back to riverbank tonight. And if ever you catch me going a-pleasuring with this provoking animal again!’-He snorted, and during the rest of that weary trudge addressed his remarks exclusively to Mole.

On reaching the town they went straight to the station and deposited Toad in the second-class waiting-room, giving a porter twopence to keep a strict eye on him. They then left the horse at an inn stable, and gave what directions they could about the cart and its contents. Eventually, a slow train having landed them at a station not very far from Toad Hall, they escorted the spell-bound, sleep-walking Toad to his door, put him inside it, and instructed his housekeeper to feed him, undress him, and put him to bed. Then they got out their boat from the boat-house, sculled down the river home, and at a very late hour sat down to supper in their own cozy riverside parlor, to the Rat’s great joy and contentment.

The following evening the Mole, who had risen late and taken things very easy all day, was sitting on the riverbank, when the Rat, who had been looking up his friends and gossiping, came strolling along to find him. ‘Heard the news?’ he said. ‘There’s nothing else being talked about, all along the river bank. Toad went up to Town by an early train this morning. And he has ordered a large and very expensive motorcar.’