The Roman Empire Part II

As for Sulla, he became “Dictator,” which meant sole and supreme ruler of all the Roman possessions. He ruled Rome for four years, and he died quietly in his bed, having spent the last year of his life tenderly raising his cabbages, as was the custom of so many Romans who had spent a lifetime killing their fellowmen.

But conditions did not grow better. On the contrary, they grew worse. Another general, Gnaeus Pompeius, or Pompey, a close friend of Sulla, went east to renew the war against the ever troublesome Mithridates. He drove that energetic potentate into the mountains where Mithridates took poison and killed himself, well knowing what fate awaited him as a Roman captive. Next, he re-established the authority of Rome over Syria, destroyed Jerusalem, roamed through western Asia, trying to revive the myth of Alexander the Great, and at last (in the year 62) returned to Rome with a dozen shiploads of defeated Kings and Princes and Generals, all of whom were forced to march in the triumphal procession of this enormously popular Roman who presented his city with the sum of forty million dollars in plunder.

It was necessary that the government of Rome be placed in the hands of a strong ruler. Only a few months before, the town had almost fallen into the hands of a good-for-nothing young aristocrat by the name of Catiline, who had gambled away his money and hoped to reimburse himself for his losses by a little plundering. Cicero, a public-spirited lawyer, had discovered the plot, had warned the Senate, and had forced Catiline to flee. But there were other young men with similar ambitions and it was no time for idle talk.

Pompey organized a triumvirate which was to take charge of affairs. He became the leader of this Vigilante Committee. Gaius Julius Caesar, who had made a reputation for himself as governor of Spain, was the second in command. The third was an indifferent sort of person by the name of Crassus. He had been elected because he was incredibly rich, having been a successful contractor of war supplies. Crassus soon went upon an expedition against the Parthians and was killed.

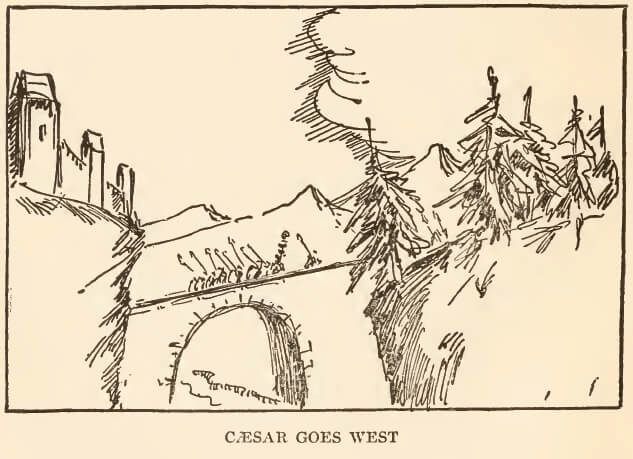

As for Caesar, who was by far the ablest of the three, he decided that he needed a little more military glory to become a popular hero. He crossed the Alps and conquered that part of the world which is now called France. Then he hammered a solid wooden bridge across the Rhine and invaded the land of the wild Teutons. Finally, he took ship and visited England. Heaven knows where he might have ended if he had not been forced to return to Italy. Pompey, so he was informed, had been appointed dictator for life. This of course meant that Caesar was to be placed on the list of the “retired officers,” and the idea did not appeal to him. He remembered that he had begun life as a follower of Marius. He decided to teach the Senators and their “dictator” another lesson. He crossed the Rubicon River which separated the province of Cis-alpine Gaul from Italy. Everywhere he was received as the “friend of the people.” Without difficulty Caesar entered Rome and Pompey fled to Greece. Caesar followed him and defeated his followers near Pharsalus. Pompey sailed across the Mediterranean and escaped to Egypt. When he landed he was murdered by order of young king Ptolemy. A few days later Caesar arrived. He found himself caught in a trap. Both the Egyptians and the Roman garrison which had remained faithful to Pompey, attacked his camp.

Fortune was with Caesar. He succeeded in setting fire to the Egyptian fleet. Incidentally the sparks of the burning vessels fell on the roof of the famous library of Alexandria (which was just off the water front,) and destroyed it. Next, he attacked the Egyptian army, drove the soldiers into the Nile, drowned Ptolemy, and established a new government under Cleopatra, the sister of the late king. Just then word reached him that Pharnaces, the son and heir of Mithridates, had gone on the war-path. Caesar marched northward, defeated Pharnaces in a war which lasted five days, sent word of his victory to Rome in the famous sentence “veni, vidi, vici,” which is Latin for “I came, I saw, I conquered,” and returned to Egypt where he fell desperately in love with Cleopatra, who followed him to Rome when he returned to take charge of the government, in the year 46. He marched at the head of not less than four different victory-parades, having won four different campaigns.

Then Caesar appeared in the Senate to report upon his adventures, and the grateful Senate made him “dictator” for ten years. It was a fatal step.

The new dictator made serious attempts to reform the Roman state. He made it possible for freemen to become members of the Senate. He conferred the rights of citizenship upon distant communities as had been done in the early days of Roman history. He permitted “foreigners” to exercise influence upon the government. He reformed the administration of the distant provinces which certain aristocratic families had come to regard as their private possessions. In short, he did many things for the good of the majority of the people but which made him thoroughly unpopular with the most powerful men in the state. Half a hundred young aristocrats formed a plot “to save the Republic.” On the Ides of March (the fifteenth of March according to that new calendar which Caesar had brought with him from Egypt) Caesar was murdered when he entered the Senate. Once more Rome was without a master.

There were two men who tried to continue the tradition of Caesar’s glory. One was Antony, his former secretary. The other was Octavian, Caesar’s grand-nephew and heir to his estate. Octavian remained in Rome, but Antony went to Egypt to be near Cleopatra with whom he too had fallen in love, as seems to have been the habit of Roman generals.

A war broke out between the two. In the battle of Actium, Octavian defeated Antony. Antony killed himself and Cleopatra was left alone to face the enemy. She tried very hard to make Octavian her third Roman conquest. When she saw that she could make no impression upon this very proud aristocrat, she killed herself, and Egypt became a Roman province.

As for Octavian, he was a very wise young man and he did not repeat the mistake of his famous uncle. He knew how people will shy at words. He was very modest in his demands when he returned to Rome. He did not want to be a “dictator.” He would be entirely satisfied with the title of “the Honorable.” But when the Senate, a few years later, addressed him as Augustus—the Illustrious—he did not object and a few years later the person in the street called him Caesar, or Kaiser, while the soldiers, accustomed to regard Octavian as their Commander-in-chief referred to him as the Chief, the Imperator or Emperor. The Republic had become an Empire, but the average Roman was hardly aware of the fact.

In 14 A.D. his position as the Absolute Ruler of the Roman people had become so well established that he was made an object of that divine worship which hitherto had been reserved for the gods. And his successors were true “Emperors”—the absolute rulers of the greatest empire the world had ever seen.

If the truth be told, the average citizen was sick and tired of anarchy and disorder. They did not care who ruled them provided the new master gave them a chance to live quietly and without the noise of eternal street riots. Octavian assured his subjects forty years of peace. Octavian had no desire to extend the frontiers of his domains, In the year 9 A.D. he had contemplated an invasion of the northwestern wilderness which was inhabited by the Teutons. But Varrus, his general, had been killed with all his men in the Teutoburg Woods, and after that the Romans made no further attempts to civilize these wild people.

The Roman people concentrated their efforts upon the gigantic problem of internal reform. But it was too late to do much good. Two centuries of revolution and foreign war had repeatedly killed the best people among the younger generations. It had ruined the class of the free farmers. It had introduced slave labor, against which no freeman could hope to compete. It had turned the cities into beehives inhabited by pauperized and unhealthy mobs of runaway peasants. It had created a large bureaucracy—petty officials who were underpaid and who were forced to take graft in order to buy bread and clothing for their families. Worst of all, it had accustomed people to violence, to bloodshed, to a barbarous pleasure in the pain and suffering of others.

Outwardly, the Roman state during the first century of our era was a magnificent political structure, so large that Alexander’s empire became one of its minor provinces. Underneath this glory there lived millions upon millions of poor and tired human beings, toiling like ants who have built a nest underneath a heavy stone. They worked for the benefit of someone else. They shared their food with the animals of the fields. They lived in stables. They died without hope.

It was the seven hundred and fifty-third year since the founding of Rome. Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus Augustus was living in the palace of the Palatine Hill, busily engaged upon the task of ruling his empire.

In a little village of distant Syria, Mary, the wife of Joseph the Carpenter, was tending her little boy, born in a stable of Bethlehem.

This is a strange world.

Before long, the palace and the stable were to meet in open combat.

And the stable was to emerge victorious.