Books about History

1st Grade

2nd Grade

3rd Grade

4th Grade

5th Grade

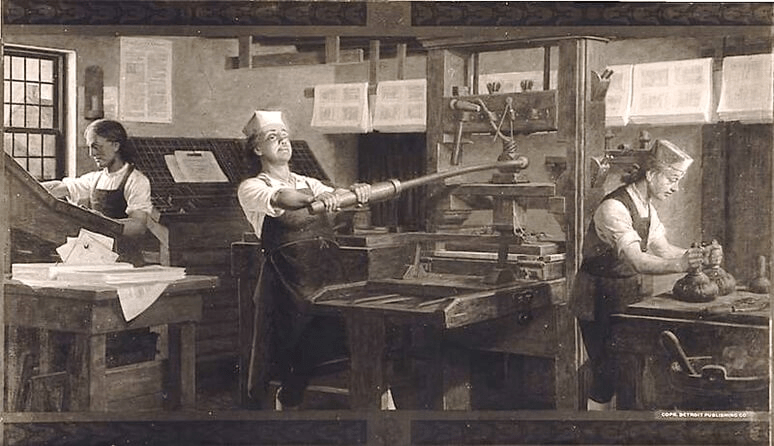

I suppose people began to notice and talk about this studious young workman. One day Keimer, the printer for whom Franklin was at work, saw coming toward his office, Sir William Keith, the governor of the province of Pennsylvania, and another gentleman, both finely dressed after the fashion of the time, in powdered periwigs and silver knee buckles. Keimer was delighted to have such visitors, and he ran down to meet the men. But imagine his disappointment when the governor asked to see Franklin and led away the young printer in leather breeches to talk with him in the tavern.

The governor wanted Franklin to set up a printing office of his own, because both Keimer and the other masterprinter in Philadelphia were poor workmen. But Franklin had no money, and it took a great deal to buy a printing press and types in that day. Franklin told the governor that he did not believe his father would help him to buy an outfit. But the governor wrote a letter himself to Franklin’s father, asking him to start Benjamin in business.

So Franklin went back to Boston in a better plight than that in which he had left. He had on a brand new suit of clothes, he carried a watch, and he had some silver in his pockets. His father and mother were glad to see him once more, but his father told him he was too young to start in business for himself.

Franklin returned to Philadelphia. Governor Keith, who was one of those gentlemen that make many promising speeches, now offered to start Franklin himself. He wanted him to go to London to buy the printing press. He promised to give the young man letters to people in London, and one that would get him the money to buy the press.

But, somehow, every time that Franklin called on the governor for the letters he was told to call again. At last, Franklin went on shipboard, thinking the governor had sent the letters in the ship’s letterbag. Before the ship got to England the bag was opened, and no letters for Franklin were found. A gentleman now told Franklin that Keith made a great many such promises, but he never kept them. Fine clothes do not make a fine gentleman.

So Franklin was left in London without money or friends. But he got work as a printer, and learned some things about the business that he could not learn in America. The English printers drank a great deal of beer. They laughed at Franklin because he did not use beer, and they called him the “Water American.” But Franklin wasn’t a fellow to be afraid of ridicule. The English printers told Franklin that water would make him weak, but they were surprised to find him able to lift more than any of them. Franklin was also a strong swimmer. In London, Franklin kept up his reading. He paid a man who kept a secondhand bookstore for permission to read his books.

Franklin came back to Philadelphia as clerk for a merchant, but the merchant soon died, and Franklin went to work again for his old master, Keimer. He was very useful, for he could make ink and cast type when they were needed, and he also engraved some designs on type metal. Keimer once fell out with Franklin and discharged him, but he begged him to come back when there was some paper money to be printed, which Keimer could not print without Franklin’s help in making the engravings.

In 1676, just a hundred years before the American Revolution, the people of Virginia were very much oppressed by Sir William Berkeley, the governor appointed by the king of England. Their property was taken away by unjust taxes and in other ways. The governor had managed to get all the power into his own hands and those of his friends.

This was the time of King Philip’s War in New England. The news of this war made the American Indians of Virginia uneasy, and at length the Susquehannas and other tribes attacked the frontiers. Governor Berkeley would not do anything to protect the people on the frontier, because he was making a great deal of money out of the trade with friendly Indians. If troops were sent against them, this profitable trade would be stopped.

When many hundreds of people on the frontier had been put to death, some three hundred men formed themselves into a company to fight the Indians. But Berkeley refused to allow anyone to take command of this troop or to let them go against the Indians.

There was a young gentleman named Nathaniel Bacon, who had come from England three years before. He was a member of the governor’s council and an educated man. He begged the governor to let him lead this company of three hundred men against the Indians, but the old governor refused.

Bacon disagreed and wished to fight the Indians. He went to the camp of these men, to see and encourage them. But when they saw him, they set up a cry, “A Bacon! A Bacon! A Bacon!” This was the way of cheering a man at that day and choosing him for a leader.

Bacon knew that the governor might put him to death if he disobeyed orders, but he wished to defend his fellow colonists.

Berkeley gathered his friends and started after Bacon, declaring that he would hang Bacon for going to war without orders. While the old governor was looking for Bacon, the people down by the coast rose in favor of Bacon. The governor had to make peace with them by promising to let them choose a new legislature.

When Bacon got back from the Indian country, the frontier people cheered him as their deliverer. They kept guard night and day over his house. They were afraid the angry governor would send men to kill him.

The people of his county elected Bacon a member of the new Legislature. But they were afraid the governor might harm him. Forty of them with guns went down to Jamestown with him in a sloop. With the help of two boats and a ship, the governor captured Bacon’s sloop, and brought Bacon into Jamestown. But as the angry people were already rising to defend their leader, Berkeley was afraid to hurt him. He made him apologize, and restored him to his place in the Council.

But that night, Bacon was warned that the next day he would be seized again, and that the roads and river were guarded to keep him from getting away. So Bacon took horse suddenly and galloped out of Jamestown in the darkness. The next morning, the governor sent men to search the house where Bacon had stayed. Berkeley’s men stuck their swords through the beds, thinking Bacon hidden there.

But Bacon was already among friends. When the country people heard that Bacon was in danger, they seized their guns and vowed to kill the governor and all his party. Bacon was quickly marching on Jamestown with five hundred angry men at his back. The people refused to help the governor, and Bacon and his men entered Jamestown. It was their turn to guard the roads and keep Berkeley in.

The old governor offered to fight the young captain single-handed, but Bacon told him he would not harm him. Bacon forced the governor to sign a commission appointing Bacon a general. Bacon also made the Legislature pass good laws for the relief of the people. These laws were remembered long after Nathaniel Bacon’s death, and were known as “Bacon’s Laws.”

While this work of doing away with bad laws and making good ones was going on, the Indians attacked at a place only about twenty miles from Jamestown. General Bacon promptly started for the Indian country with his little army. But, just as he was leaving the settlements, he heard that the governor was raising troops to take him when he should get back; so he turned around and marched swiftly back to Jamestown.

The governor had called out the militia, but when they learned that instead of taking them to fight the Indians they were to go against Bacon, they all began to murmur, “Bacon! Bacon! Bacon!” Then they left the field and went home, and the old governor fainted with disappointment. He was forced to flee for safety to the eastern shore of Chesapeake Bay, and the government fell into the hands of General Bacon.

Bacon had an enemy on each side of him. No sooner had Berkeley gone than the Indians again attacked. Bacon once more marched against them and killed many. He and his men lived on horseflesh and chinquapin nuts during this expedition.

When Bacon got back to the settlements and had dismissed all but one hundred and thirty-six of his men, he heard that Governor Berkeley had gathered together seventeen vessels and six hundred sailors and others, and with these had taken possession of Jamestown. Worn out as they were with fatigue and hunger, Bacon persuaded his band to march straight for Jamestown, so as to take Berkeley by surprise.

As the weary and dusty veterans of the Indian war hurried onward to Jamestown, the people cheered the company. The women called after Bacon, “General, if you need help, send for us!” So fast did these men march that they reached the narrow neck of sand that connected Jamestown with the mainland before the governor had heard of their coming. Bacon’s men dug trenches in the night and shut in the governor and his people.

After a while, Bacon got some cannon. He wanted to put them up on his breastworks without losing the life of any of his brave soldiers. So he sent to the plantations nearby and brought to his camp the wives of the chief men in the governor’s party. These ladies he had sit in front of his works until his cannon were in place. He knew that the enemy would not fire on the ladies. When he had finished, he sent the ladies home.

Great numbers of the people now flocked to General Bacon’s standard, and the governor and his followers left Jamestown in their vessels. Knowing that they would try to return, Bacon ordered the town to be burned to the ground. Almost all of the people except those on the eastern shore sided with Bacon, who now did his best to put the government in order. But the hardships he had been through were too much for him. He sickened and died. His friends knew that Berkeley would soon get control again, now that their leader was dead. They knew that his enemies would dig up Bacon’s body and hang it, after the fashion of that time. No one knows where they buried Bacon’s body, but as they put stones in his coffin, they must have sunk it in the river.

Governor Berkeley got back his power and hanged many of Bacon’s friends. But the king of England removed Berkeley in disgrace, and he died of a broken heart. The governors who came after were generally careful not to oppress the people too far. They were afraid another Bacon might rise up against them.

Ancient History is a fascinating subject. Here is a timeline of many of the major events that happened in History. An approximate date is also given next to the event. With the list of events will be links to articles giving more information about the event. Some of the resources are from secular sources such as The Story of Mankind.

Thirteen years after the first settlement at Jamestown, a colony was planted in New England. We have seen that the rough-and-ready John Smith was the man negotiated best with the American Indians in Virginia. So the first colony in New England had also its soldier, a brave and rather hot-tempered little man — Captain Myles Standish.

Myles Standish was born in England in 1584. He became a soldier, and, like John Smith, went to fight in the Low Country — that is in what we now call Holland — which was at that time fighting to gain its liberty from Spain.

The Government of Holland let people be religious in their own way, as our country does now. In nearly all other countries at that time, people were punished if they did not worship after the manner of the established church of the land. A little band of people in the north of England had set up a church of their own. For this they were persecuted. To get out of the way of their troubles, they sold their houses and goods and went over to Holland. These are the people that we now call “the Pilgrims,” because of their wanderings.

Captain Standish, who was also from the north of England, met these countrymen of his in Holland. He liked their simple service and honest ways, and he lived among them though he did not belong to their church.

The Pilgrims remained about thirteen years in Holland. By this time, they had made up their minds to seek a new home in the wild woods of America. About a hundred of them bade the rest goodbye and sailed for America in the Mayflower in 1620. As there might be some fighting to do, the brave soldier Captain Myles Standish went along with them.

The ship first reached land at Cape Cod. Captain Standish and sixteen men landed and marched along the shore looking for a place to settle. In one spot, they found the ground freshly patted down. Digging here, they discovered Indian baskets filled with corn. Indian corn is an American plant, and they had never before seen it. The beautiful grains, red, yellow, and white, were a “goodly sight,” as they said. Some of this corn they took with them to plant the next spring. The Pilgrims paid the Indians for this seed corn when they found the right owners.

Standish made his next trip in a boat. This time he found some Indian wigwams covered and lined with mats. In December, Captain Standish made a third trip along the shore. It was now so cold that the spray froze to the clothes of his men while they rowed. At night they slept behind a little barricade made of logs and boughs, so as to be ready if the Indians should attack them.

One morning some of the men carried all their guns down to the waterside and laid them in the boat, in order to be ready for a start as soon as breakfast should be finished. But all at once there broke on their ears a sound they had never heard before. It was the wild war-whoop of a band of Indians whose arrows rained around Standish and his men. Some of the men ran to the boat for their guns, at which the Indians raised a new yell and sent another lot of arrows flying after them. But once the Pilgrims were in possession of their guns, they fired a volley which made the Indians retreat. One brave Indian lingered behind a tree to fight it out alone; but when a bullet struck the tree and sent bits of bark and splinters rattling about his head, he thought better of it, and retreated after his friends into the woods.

Captain Standish and his men at length came to a place which John Smith, when he explored the coast, had called Plymouth. Here the Pilgrims found a safe harbor for ships and some running brooks from which they might get fresh water. They therefore selected it for their landing place. There had once been an Indian town here, but all the Indians in it had died of a pestilence three or four years before this time. The Indian corn fields were now lying idle, which was lucky for the Pilgrims, since otherwise they would have had to chop down trees to clear a field.

The Pilgrims landed on the 21st day of December, in our way of counting, or, as some say, the 22d. They built some rough houses, using paper dipped in oil instead of window-glass. But the bad food and lack of warm houses or clothing brought on a terrible sickness, so that here, as at Jamestown, one half of the people died in the first year. Captain Standish lost his wife, but he himself was well enough to nurse the sick. Though he was a leader, he did not neglect to do the hardest and most disagreeable work for his sick and dying neighbors.

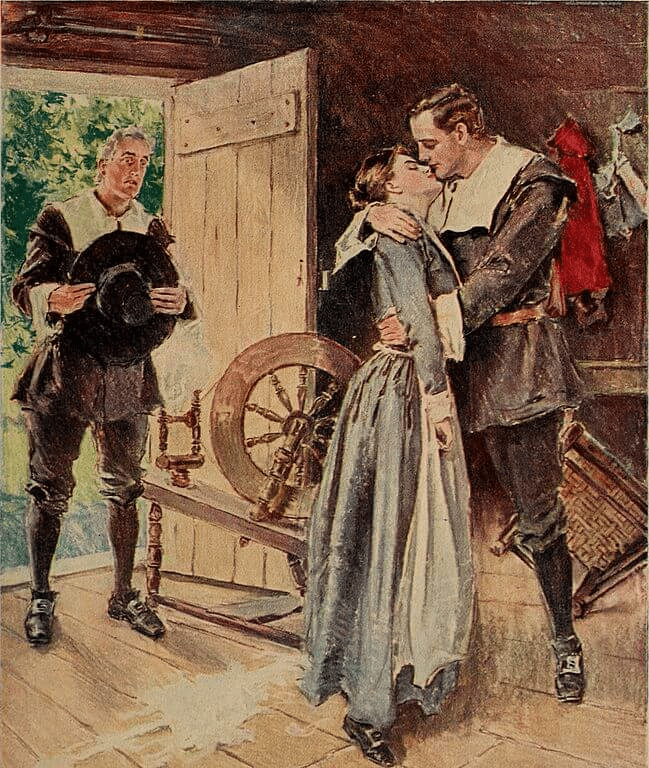

As there were not many houses, the people in Plymouth were divided into nineteen families, and the single men had to live with one or another of these families. A young man named John Alden was assigned to live in Captain Standish’s house. Some time after Standish’s wife died, the captain thought he would like to marry a young woman named Priscilla Mullins. But as Standish was much older than Priscilla, and a rough spoken soldier in his ways, he asked his young friend Alden to go to the Mullins house and try to secure Priscilla for him.

It seems that John Alden loved Priscilla, and she cared for him in return. But Standish did not know this, and poor Alden felt bound to do as the captain requested. In that day, the father of the young lady was asked first. So Alden went to Mr. Mullins and told him what a brave man Captain Standish was. Then he asked if Captain Standish might marry Priscilla.

“I have no objection to Captain Standish,” said Priscilla’s father, “but this is a matter she must decide.” So he called in his daughter and told her in Alden’s presence that the young man had come to ask her hand in marriage with the brave Captain Standish. Priscilla had no notion of marrying the captain. She looked at the young man a moment, and then said: “Why don’t you speak for yourself, John?”

The result was that she married John Alden, and Captain Standish married another woman. You may read this story, a little changed, in Longfellow’s poem called “The Courtship of Miles Standish.”

Three hundred years ago England was rather poor in people and in money. Spain had become rich and important by her gold mines in the West Indies and the central parts of America. Portugal had been enriched by finding a way around Africa to India, where many things such as silks and spices were bought to be sold in Europe at high prices. Some thoughtful men in England had an idea that as the Portuguese had reached India by sailing around the Eastern Continent on the south, the English might find a way to sail to India around the northern part of Europe and Asia. By this means, the English ships would also be able to get the precious things to be found in the East.

For this purpose, some London merchants founded the Muscovy Company, with old Sebastian Cabot at its head. This Muscovy Company had not succeeded in finding a way to China around the north of Europe, but in trying to do this its ships had opened a valuable trade with Russia, or Muscovy as it was then called, which was a country but little known before.

One of the founders of this Muscovy Company was a rich man named Henry Hudson. It is thought that he was the grandfather of Henry Hudson, the explorer. The merchants who made up this company were in the habit of sending out their sons, while they were boys, in the ships of the company, to learn to sail vessels and to gain a knowledge of the languages and habits of trade in distant countries. Henry was sent to sea while a lad, and was no doubt taught by the ship captains all about sailing vessels. When he grew to be a man, he wished to make himself famous by finding a northern way to China.

In the spring of 1607, almost four months after Captain Smith had left London with the colony bound for Jamestown, his friend Hudson was sent out by the Muscovy Company to try once more for a passage to China. He had only a little ship, which was named Hopewell, and he had but ten men, including his own son John Hudson. He found that there was no way to India by the north pole. But he got farther north than any other man.

Hudson made an important discovery on this voyage. He found whales in the Arctic Seas, and the Muscovy Company now fitted out whaling ships to catch them. The next year the brave Hudson tried to pass between Spitzbergen and Nova Zembla, but he was again bumping against the walls of ice that fence in the frozen pole.

By this time, the Muscovy Company was discouraged and gave up trying to get to India by going around the north of Europe. They thought it better to make money out of the whale-fishery that Hudson had found. But in Holland, there was the Dutch East India Company, which sent ships around Africa to India. They had heard of the voyages of Hudson, who had got the name of “the bold Englishman.” The Dutch Company was afraid that the English, with Hudson’s help, might find a nearer way by the north, and so get the trade away from them. So they sent for “the bold Englishman,” and hired him to find this new route for them.

Hudson left Amsterdam in 1609 in a yacht called “The Half Moon.” He sailed around Norway and found his old enemy the ice as bad as ever about Nova Zembla. Some of the Dutch sailors on Hudson’s ship were used to the heat of the East Indies. The frosty air of these icy seas was very disagreeable to them, and they rebelled against their captain.

Just before leaving home, Hudson had received a letter from his friend Captain John Smith, in Virginia, telling him that there was a strait leading into the Pacific Ocean, to the north of Virginia. Smith had no doubt misunderstood some story of the Indians. But now that the seamen would not go on through the cold seas at the north of Europe, Hudson persuaded them to turn about and sail with him to America to look up the way to India that Smith had written about.

So they turned to the westward and sailed to Newfoundland, and thence down the coast until they were opposite the James River. Then Hudson turned north again and began to look for a gateway through this wild and unknown coast. He sailed into Delaware Bay, as ships do now on their way to Philadelphia. Then he sailed out and followed along the shores till he came to the opening by which thousands of ships nowadays go into New York.

He passed into New York Bay, where no vessel had ever been before. He said it was “a very good land to fall in with, and a pleasant land to see.” The New Jersey Indians swarmed about the ship dressed in fur robes and feather mantles and wearing copper necklaces. Hudson thought some of the many waterways about New York harbor must lead into the Pacific.

He sent men out in a boat to examine the bays and rivers. They declared that the land was “as pleasant with grass and flowers as ever they had seen, and very sweet smells.” But before they got back, some Indians attacked the boat and killed one man by shooting him with an arrow.

When the Indians came around the ship again, Hudson made two of them prisoners and dressed them up in red coats. The rest he drove away. As he sailed farther up from the sea, twenty-eight dug-out canoes filled with men, women, and children, paddled about the ship. The colonists traded with them, giving them trinkets for oysters and beans, but none were allowed to come aboard. As the ship sailed on up the river that we now call the Hudson, the two Indian prisoners saw themselves carried farther and farther from their home. One morning, they jumped out of a porthole and swam ashore. They stood on the shore and mocked the men on the Half Moon as she sailed away up the river.

Hudson’s ship anchored again opposite the Catskill Mountains, and here he found some very friendly Indians, who brought corn, pumpkins, and tobacco to sell to the crew. Still farther up the river, Hudson visited a tribe on shore and wondered at their great heaps of corn and beans. The chief lived in a round bark house. Captain Hudson was made to sit on a mat and eat from a red wooden bowl. The Indians wished him to stay all night. They broke their arrows and threw them into the fire to show their friendliness.

Hudson found the river growing shallower. When he got near where Albany now stands, he sent a rowboat yet higher up. Then he concluded that this was not the way to the Pacific. He turned around and sailed down the river and then across the ocean to England. The Half Moon returned to Holland, and the Dutch sent out other ships to trade in the river which Hudson had found. In the course of time, they planted a colony where New York now stands.

Captain Hudson did not try to go around the north of Europe any more. But the next spring he sailed in an English ship to look for a way around the north side of the American Continent. On this voyage he discovered the great bay that is now called Hudson’s Bay.

In this bay he spent the winter. His men suffered with hunger and sickness. In the summer of 1611, after he had, with tears in his eyes, divided his last bread with his men, these wicked fellows put him into a boat with some sick sailors and cast them all adrift in the great bay.

The men on the ship shot some birds for food, but in a fight with the Indians some of the leaders in the plot against Hudson were killed. The seamen, as they sailed homeward, grew so weak from hunger that they had to sit down to steer the vessel. When at last Juet, the mate, who had put Hudson overboard, had himself died of hunger, and all the rest had lain down in despair to die, they were saved by meeting another ship.

Captain Smith tried very hard to persuade English people to plant a colony in New England. He finally set out with only sixteen men to begin a settlement there, he had made friends with the New England Indians, and he was sure that with a few men he could still succeed in planting a colony. But he had very bad luck. He first lost the masts of his vessels in a storm. He returned to England again and set sail in a smaller ship. He was then chased by a pirate-vessel. Smith found, on hailing this ship, that some of the men on board had been soldiers under him in the Turkish wars. They proposed to him to be their captain, but he did not want to command such rogues.

Smith’s little vessel had no sooner got away from these villains, then he was chased by a French ship. He had to threaten to blow up his ship to get his men to fight. He escaped again, but the next time he was met by a fleet of French privateers. They made Smith come aboard one of their vessels to show his papers. After they had got him out of his ship, they held him prisoner and took possession of his cargo. They afterward agreed to let him have his vessel again, as he was still determined to sail to New England; but his men wanted to turn back. So, while Smith was on the French ship, his own men ran away with his vessel and got back to England. Thus, his plan for a colony failed.

Smith spent his summer on the French fleet. When the French privateers were fighting with an English vessel, they made Smith a prisoner in the cabin; but when they fought with Spanish ships they would put Smith at the guns and make him fight with them. Smith reached England at last and had the satisfaction of having some of his runaway sailors put in prison. He never tried to plant another colony, though he was very much pleased with the success of the Plymouth colony which settled in New England a few years later than this. This brave, roving, fighting, boasting captain died in 1631, when he was fifty-two years old.