Joshua of Nazareth (Jesus)

Instructor Note: No such letters as included in this lesson exist. This chapter features imaginary letters written by the book author, Van Loon, to convey his personal retelling of the story of Jesus.

In the autumn of the year of the city 783 (which would be 62 A.D., in our way of counting time) Aesculapius Cultellus, a Roman physician, wrote to his nephew who was with the army in Syria as follows:

My dear Nephew,

A few days ago I was called in to prescribe for a sick man named Paul. He appeared to be a Roman citizen of Jewish parentage, well-educated and of agreeable manners. I had been told that he was here in connection with a lawsuit, an appeal from one of our provincial courts, Caesarea or some such place in the eastern Mediterranean. He had been described to me as a “wild and violent” fellow who had been making speeches against the People and against the Law. I found him very intelligent and of great honesty.

A friend of mine who used to be with the army in Asia Minor tells me that he heard something about him in Ephesus where he was preaching sermons about a strange new god. I asked my patient if this were true and whether he had told the people to rebel against the will of our beloved Emperor. Paul answered me that the Kingdom of which he had spoken was not of this world and he added many strange utterances which I did not understand, but which were probably due to his fever.

His personality made a great impression upon me and I was sorry to hear that he was killed on the Ostian Road a few days ago. Therefore, I am writing this letter to you. When next you visit Jerusalem, I want you to find out something about my friend Paul and the strange Jewish prophet, who seems to have been his teacher. Our slaves are getting much excited about this so-called Messiah, and a few of them, who openly talked of the new kingdom (whatever that means) have been crucified. I would like to know the truth about all these rumors and I am

Your devoted Uncle,

AESCULAPIUS CULTELLUS.

Six weeks later, Gladius Ensa, the nephew, a captain of the VII Gallic Infantry, answered as follows:

My dear Uncle,

I received your letter and I have obeyed your instructions.

Two weeks ago our brigade was sent to Jerusalem. There have been several revolutions during the last century and there is not much left of the old city. We have been here now for a month and tomorrow we shall continue our march to Petra, where there has been trouble with some of the Arab tribes. I shall use this evening to answer your questions, but pray do not expect a detailed report.

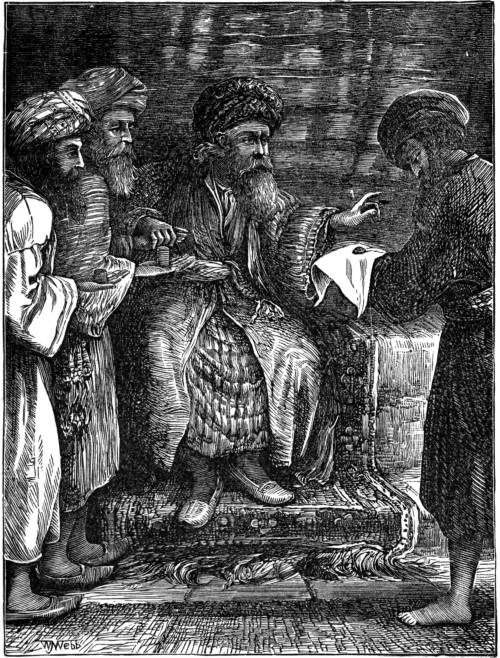

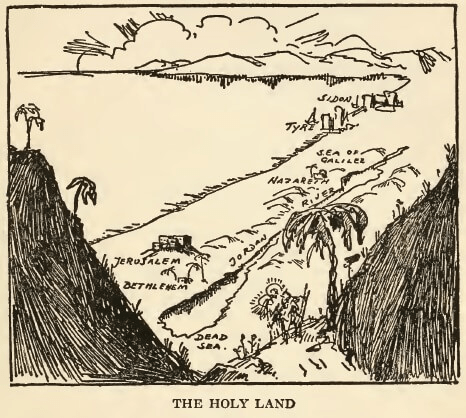

I have talked with most of the older men in this city but few have been able to give me any definite information. A few days ago, a peddler came to the camp. I bought some of his olives and I asked him whether he had ever heard of the famous Messiah who was killed when he was young. He said that he remembered it very clearly, because his father had taken him to Golgotha (a hill just outside the city) to see the execution, and to show him what became of the enemies of the laws of the people of Judaea. He gave me the address of one Joseph, who had been a personal friend of the Messiah and told me that I had better go and see him if I wanted to know more.

This morning I went to call on Joseph. He was quite an old man. He had been a fisherman on one of the fresh-water lakes. His memory was clear, and from him at last I got a fairly definite account of what had happened during the troublesome days before I was born.

Tiberius, our great and glorious emperor, was on the throne, and an officer of the name of Pontius Pilatus was governor of Judaea and Samaria. Joseph knew little about this Pilatus. He seemed to have been an honest enough official who left a decent reputation as procurator of the province. In the year 755 or 756 (Joseph had forgotten when) Pilatus was called to Jerusalem on account of a riot. A certain young man (the son of a carpenter of Nazareth) was said to be planning a revolution against the Roman government. Strangely enough our own intelligence officers, who are usually well informed, appear to have heard nothing about it, and when they investigated the matter they reported that the carpenter was an excellent citizen and that there was no reason to proceed against him. But the old-fashioned leaders of the Jewish faith, according to Joseph, were much upset. They greatly disliked his popularity with the masses of the poorer Hebrews. The “Nazarene” (so they told Pilatus) had publicly claimed that a Greek or a Roman or even a Philistine, who tried to live a decent and honorable life, was quite as good as a Jew who spent his days studying the ancient laws of Moses. Pilatus does not seem to have been impressed by this argument, but when the crowds around the temple threatened to lynch Jesus, and kill all his followers, he decided to take the carpenter into custody to save his life.

He does not appear to have understood the real nature of the quarrel. Whenever he asked the Jewish priests to explain their grievances, they shouted “heresy” and “treason” and got terribly excited. Finally, so Joseph told me, Pilatus sent for Joshua (that was the name of the Nazarene, but the Greeks who live in this part of the world always refer to him as Jesus) to examine him personally. He talked to him for several hours. He asked him about the “dangerous doctrines” which he was said to have preached on the shores of the sea of Galilee. But Jesus answered that he never referred to politics. He was not so much interested in the bodies of men as in Man’s soul. He wanted all people to regard their neighbors as their brothers and to love one single god, who was the father of all living beings.

Pilatus, who seems to have been well versed in the doctrines of the Stoics and the other Greek philosophers, does not appear to have discovered anything seditious in the talk of Jesus. According to my informant he made another attempt to save the life of the kindly prophet. He kept putting the execution off. Meanwhile the Jewish people, lashed into fury by their priests, got frantic with rage. There had been many riots in Jerusalem before this and there were only a few Roman soldiers within calling distance. Reports were being sent to the Roman authorities in Caesarea that Pilatus had “fallen a victim to the teachings of the Nazarene.” Petitions were being circulated all through the city to have Pilatus recalled, because he was an enemy of the Emperor. You know that our governors have strict instructions to avoid an open break with their foreign subjects. To save the country from civil war, Pilatus finally sacrificed his prisoner, Joshua, who behaved with great dignity and who forgave all those who hated him. He was crucified amidst the howls and the laughter of the Jerusalem mob.

That is what Joseph told me, with tears running down his old cheeks. I gave him a gold piece when I left him, but he refused it and asked me to hand it to one poorer than himself. I also asked him a few questions about your friend Paul. He had known him slightly. He seems to have been a tent maker who gave up his profession that he might preach the words of a loving and forgiving god, who was so very different from that Jehovah of whom the Jewish priests are telling us all the time. Afterwards, Paul appears to have travelled much in Asia Minor and in Greece, telling the slaves that they were all children of one loving Father and that happiness awaits all, both rich and poor, who have tried to live honest lives and have done good to those who were suffering and miserable.

I hope that I have answered your questions to your satisfaction. The whole story seems very harmless to me as far as the safety of the state is concerned. But then, we Romans never have been able to understand the people of this province. I am sorry that they have killed your friend Paul. I wish that I were at home again, and I am, as ever,

Your dutiful nephew,

GLADIUS ENSA.