The Story of Doctor Dolittle Chapter 4: A Message from Africa

Chapter 4: A Message from Africa

That winter was a very cold one. And one night in December, when they were all sitting round the warm fire in the kitchen, and the Doctor was reading aloud to them out of books he had written himself in animal-language, the owl, Too-Too, suddenly said,

“Sh! What’s that noise outside?”

They all listened; and presently they heard the sound of someone running. Then the door flew open and the monkey, Chee-Chee, ran in, badly out of breath.

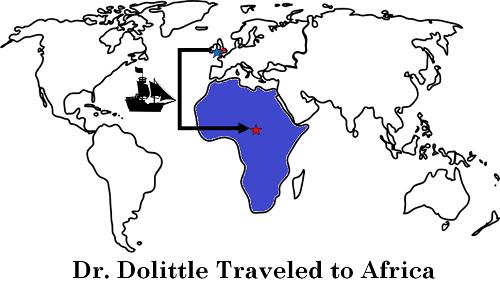

“Doctor!” he cried, “I’ve just had a message from a cousin of mine in Africa. There is a terrible sickness among the monkeys out there. They are all catching it-and they are dying in hundreds. They have heard of you, and beg you to come to Africa to stop the sickness.”

“Who brought the message?” asked the Doctor, taking off his spectacles and laying down his book.

“A swallow,” said Chee-Chee. “She is outside on the rain-butt.”

“Bring her in by the fire,” said the Doctor. “She must be perished with the cold. The swallows flew South six weeks ago!”

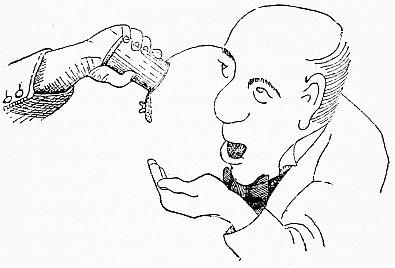

So the swallow was brought in, all huddled and shivering; and although she was a little afraid at first, she soon got warmed up and sat on the edge of the mantelpiece and began to talk.

When she had finished the Doctor said,

“I would gladly go to Africa-especially in this bitter weather. But I’m afraid we haven’t money enough to buy the tickets. Get me the money-box, Chee-Chee.”

So the monkey climbed up and got it off the top shelf of the dresser.

There was nothing in it-not a single penny!

“I felt sure there was twopence left,” said the Doctor.

“There was” said the owl. “But you spent it on a rattle for that badger’s baby when he was teething.”

“Did I?” said the Doctor-“dear me, dear me! What a nuisance money is, to be sure! Well, never mind. Perhaps if I go down to the seaside I shall be able to borrow a boat that will take us to Africa. I knew a seaman once who brought his baby to me with measles. Maybe he’ll lend us his boat-the baby got well.”

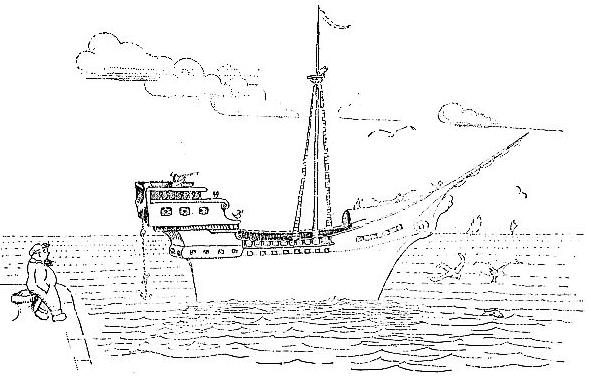

So early the next morning the Doctor went down to the sea-shore. And when he came back he told the animals it was all right-the sailor was going to lend them the boat.

Then the crocodile and the monkey and the parrot were very glad and began to sing, because they were going back to Africa, their real home. And the Doctor said,

“I shall only be able to take you three-with Jip the dog, Dab-Dab the duck, Gub-Gub the pig and the owl, Too-Too. The rest of the animals, like the dormice and the water-voles and the bats, they will have to go back and live in the fields where they were born till we come home again. But as most of them sleep through the Winter, they won’t mind that-and besides, it wouldn’t be good for them to go to Africa.”

So then the parrot, who had been on long sea-voyages before, began telling the Doctor all the things he would have to take with him on the ship.

“You must have plenty of pilot-bread,” she said-“‘hardtack’ they call it. And you must have beef in cans-and an anchor.”

“I expect the ship will have its own anchor,” said the Doctor.

“Well, make sure,” said Polynesia. “Because it’s very important. You can’t stop if you haven’t got an anchor. And you’ll need a bell.”

“What’s that for?” asked the Doctor.

“To tell the time by,” said the parrot. “You go and ring it every half-hour and then you know what time it is. And bring a whole lot of rope-it always comes in handy on voyages.”

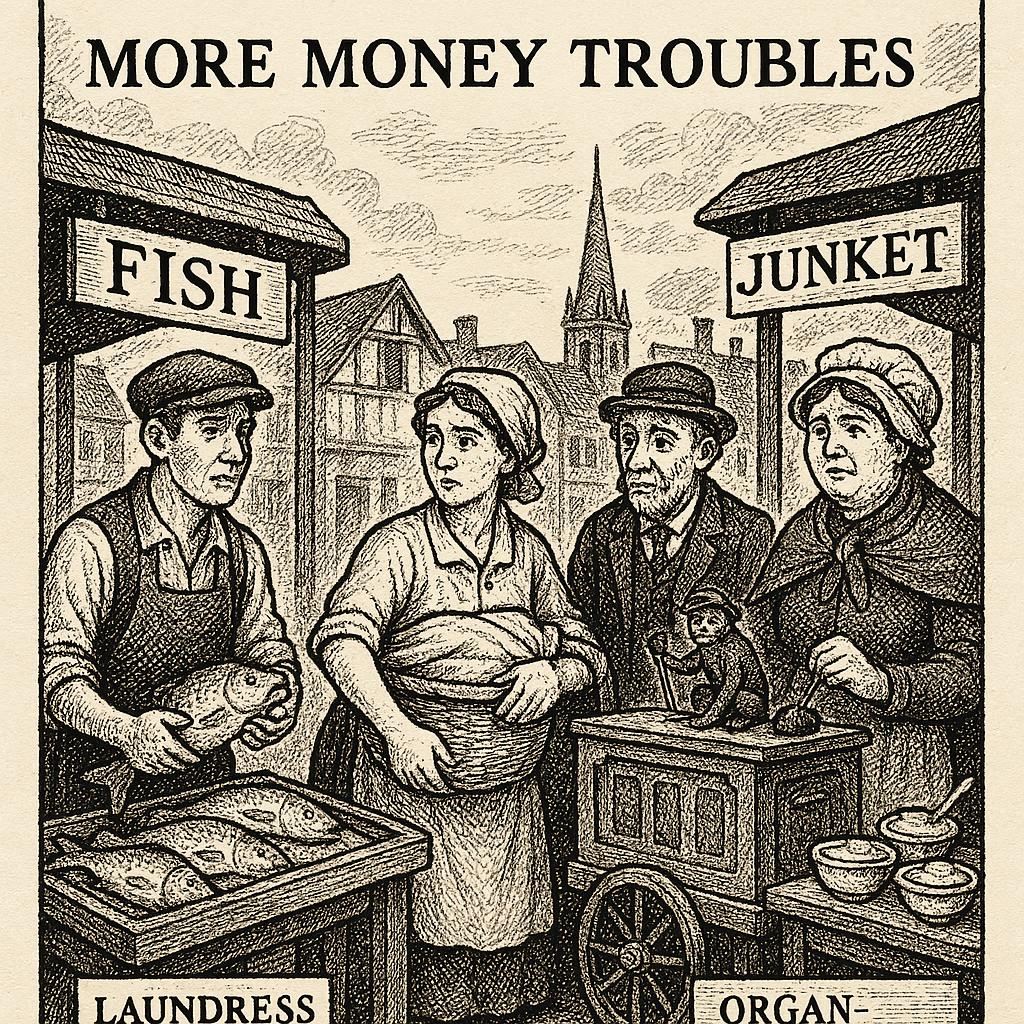

Then they began to wonder where they were going to get the money from to buy all the things they needed.

“Oh, bother it! Money again,” cried the Doctor. “Goodness! I shall be glad to get to Africa where we don’t have to have any! I’ll go and ask the grocer if he will wait for his money till I get back-No, I’ll send the sailor to ask him.”

So the sailor went to see the grocer. And presently he came back with all the things they wanted.

Then the animals packed up; and after they had turned off the water so the pipes wouldn’t freeze, and put up the shutters, they closed the house and gave the key to the old horse who lived in the stable. And when they had seen that there was plenty of hay in the loft to last the horse through the Winter, they carried all their luggage down to the seashore and got on to the boat.

The Cat’s-meat-Man was there to see them off; and he brought a large suet-pudding as a present for the Doctor because, he said he had been told, you couldn’t get suet-puddings in foreign parts.

As soon as they were on the ship, Gub-Gub, the pig, asked where the beds were, for it was four o’clock in the afternoon and he wanted his nap. So Polynesia took him downstairs into the inside of the ship and showed him the beds, set all on top of one another like book-shelves against a wall.

“Why, that’s not a bed!” cried Gub-Gub. “That’s a shelf!”

“Beds are always like that on ships,” said the parrot. “It isn’t a shelf. Climb up into it and go to sleep. That’s what you call ‘a bunk.'”

“I don’t think I’ll go to bed yet,” said Gub-Gub. “I’m too excited. I want to go upstairs again and see them start.”

“Well, this is your first trip,” said Polynesia. “You will get used to the life after a while.” And she went back up the stairs of the ship, humming this song to herself,

I’ve seen the Black Sea and the Red Sea;

I rounded the Isle of Wight;

I discovered the Yellow River,

And the Orange too-by night.

Now Greenland drops behind again,

And I sail the ocean Blue.

I’m tired of all these colors, Jane,

So I’m coming back to you.

They were just going to start on their journey, when the Doctor said he would have to go back and ask the sailor the way to Africa.

But the swallow said she had been to that country many times and would show them how to get there.

So, the Doctor told Chee-Chee to pull up the anchor and the voyage began.