Louis Daniel Armstrong (August 4, 1901 – July 6, 1971), better known as “Satchmo,” “Satch,” or “Pops,” was a legendary American jazz and blues trumpeter and singer. Widely regarded as one of the most influential figures in jazz, his career stretched over five decades, covering several key eras in the genre’s history. He earned countless honors, including the Grammy Award for Best Male Vocal Performance for Hello, Dolly! in 1965, and a posthumous Lifetime Achievement Award in 1972. His impact went beyond jazz, earning him places in the DownBeat Jazz Hall of Fame, the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, and the National Rhythm & Blues Hall of Fame, among others.

Armstrong grew up in New Orleans and rose to fame in the 1920s as a creative trumpet and cornet player who helped shape jazz, moving its focus from group improvisation to solo performances. Around 1922, he joined his mentor, Joe “King” Oliver, in Chicago to play with Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band. Known for excelling at “cutting contests,” Armstrong caught the attention of bandleader Fletcher Henderson and moved to New York City, where he became a prominent soloist and recording artist. By the 1950s, he was a global music icon, appearing frequently on radio, television, and in films. Beyond his music, he was adored as an entertainer, always cracking jokes and maintaining a joyful public persona.

Armstrong’s best known songs include “What a Wonderful World”, “La Vie en Rose”, “Hello, Dolly!”, “On the Sunny Side of the Street”, “Dream a Little Dream of Me”, “When You’re Smiling” and “When the Saints Go Marching In”. He collaborated with Ella Fitzgerald, producing three records together: Ella and Louis (1956), Ella and Louis Again (1957), and Porgy and Bess (1959). He also appeared in films such as A Rhapsody in Black and Blue (1932), Cabin in the Sky (1943), High Society (1956), Paris Blues (1961), A Man Called Adam (1966), and Hello, Dolly! (1969).

With his rich, gravelly voice, Armstrong became an influential singer and master improviser, also known for his scat singing skills. By the end of his life, his impact reached far into popular music. He was one of the first African American entertainers to “crossover” into broad popularity among white and international audiences. Though he seldom spoke publicly about racial issues—sometimes frustrating fellow Black Americans—he made headlines taking a stand for desegregation during the Little Rock Crisis. At a time when it was rare for Black men, he moved in the upper circles of American society. His recording of “Melancholy Blues” even made it onto the Voyager Golden Record, a collection of Earth’s sights and sounds sent into space.

Early life

Louis Armstrong is thought to have been born in New Orleans on August 4, 1901, though this date has long been disputed. Armstrong often said he was born on July 4, 1900. His parents were Mary Estelle “Mayann” Albert and William Armstrong. Mary, originally from Boutte, Louisiana, gave birth at home when she was about 16. A little over a year later, she had a daughter, Beatrice “Mama Lucy” Armstrong (1903–1987), whom she raised. William Armstrong left the family soon after.

Louis Armstrong lived with his grandmother until he was five, when he went back to live with his mother. He grew up in poverty in a tough neighborhood called The Battlefield, located in the southern part of Rampart Street. At six years old, he began attending the Fisk School for Boys, one of the few schools in New Orleans’ segregated system that accepted Black children.

During this time, Armstrong lived with his mother and sister and worked for the Karnoffskys, a Lithuanian Jewish family, at their home. He helped their sons, Morris and Alex, collect “rags and bones” and deliver coal. In 1969, while recovering from heart and kidney problems at Beth Israel Hospital in New York City, Armstrong wrote a memoir titled *Louis Armstrong + the Jewish Family in New Orleans, LA., the Year of 1907*, recounting his experiences working for the Karnoffsky family.

Armstrong recalls singing “Russian Lullaby” with the Karnoffsky family when their baby son David was being put to bed, crediting them with teaching him to sing “from the heart.” Interestingly, the lyrics he remembered match Irving Berlin’s “Russian Lullaby,” copyrighted in 1927—about 20 years after Armstrong said he sang it as a child. In 1969, his doctor Gary Zucker shared Berlin’s lyrics with him, and Armstrong included them in his memoir. The mix-up may have happened because he wrote the memoir more than 60 years after the events. Still, the Karnoffskys treated him with great kindness, feeding and caring for him knowing he had no father.

In his memoir, *Louis Armstrong + the Jewish Family in New Orleans, La., the Year of 1907*, Armstrong recalled realizing that the Jewish family he worked for faced discrimination from “other white folks” who thought they were superior to Jews. “I was only seven years old, but I could easily see the ungodly treatment that the white folks were handing the poor Jewish family whom I worked for,” he wrote. From them, he learned “how to live—real life and determination.” His first musical performance may have been alongside the Karnoffskys’ junk wagon, where he played a tin horn to attract customers and stand out from other hawkers. Morris Karnoffsky even gave him an advance to buy a cornet from a pawn shop. Later in life, Armstrong wore a Star of David, a gift from his Jewish manager Joe Glaser, as a tribute to the family who had helped raise him.

At 11, Armstrong left school and moved with his mother into a cramped one-room house on Perdido Street, along with Lucy and her common-law husband, Tom Lee, next door to her brother Ike and his two sons. He joined a group of boys singing in the streets for tips. Cornetist Bunk Johnson claimed he taught young Armstrong to play by ear at Dago Tony’s honky tonk, though later Armstrong credited King Oliver as his mentor. Reflecting on his youth, Armstrong said, “Every time I close my eyes blowing that trumpet of mine—I look right in the heart of good old New Orleans… It has given me something to live for.”

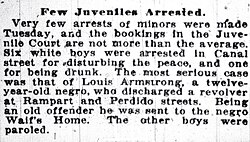

On December 31, 1912, Armstrong borrowed his stepfather’s gun without permission, fired a blank into the air, and was arrested. He spent the night at New Orleans Juvenile Court before being sentenced the next day to the Colored Waif’s Home. Life there was harsh—no mattresses, and meals often consisted of just bread and molasses. Captain Joseph Jones ran the place like a military camp, enforcing discipline through corporal punishment.

Armstrong honed his cornet skills while playing in the band. Peter Davis, a regular visitor to the home at Captain Jones’s request, became his first teacher and appointed him as the bandleader. At just 13, Armstrong’s talent with the band caught the eye of Kid Ory.

On June 14, 1914, Armstrong went to live with his father and new stepmother, Gertrude, sharing the home with two stepbrothers for a few months. After Gertrude had a daughter, his father never truly accepted him, so Armstrong moved back in with his mother, Mary Albert. In her small house, he shared a bed with his mother and sister. Still living in The Battlefield, he was surrounded by old temptations, but focused on finding work as a musician.

Armstrong landed a job at a dance hall run by Henry Ponce, a man with ties to organized crime. There, he met the towering six-foot-tall drummer Black Benny, who took him under his wing as a guide and bodyguard.

Armstrong took a short stint studying shipping management at a local community college but had to drop out when he couldn’t cover the fees. While selling coal in Storyville, he came across spasm bands, groups that made music using household items. He soaked in the early jazz sounds from bands playing in brothels and dance halls, including Pete Lala’s, where King Oliver was a regular.

Career

Riverboat education

In the late 1910s, early in his career, Armstrong played in brass bands and on riverboats in New Orleans. He toured with Fate Marable’s band aboard the steamboat Sidney, traveling up and down the Mississippi River with the Streckfus Steamers. Marable, impressed by Armstrong’s musical skill, insisted that he and the other musicians learn sight reading. Armstrong described this period as “going to the University,” as it broadened his experience with written arrangements. In 1918, when his mentor King Oliver left Kid Ory’s band to head north, Armstrong took his place and also became the second trumpet for the Tuxedo Brass Band.

During his time on the riverboats, Armstrong’s musical skills grew and evolved. By the age of 20, he could read music and became one of the first jazz musicians to take extended trumpet solos, adding his own flair and style. He also began incorporating singing into his performances.

Personal life

Pronunciation of name

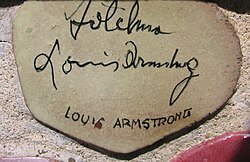

The Louis Armstrong House Museum website states:

Judging from home recorded tapes now in our Museum Collections, Louis pronounced his own name as “Lewis.” On his 1964 record “Hello, Dolly”, he sings, “This is Lewis, Dolly”, but in 1933, he made a record called “Laughin’ Louie.” Many broadcast announcers, fans, and acquaintances called him “Louie”, and in a videotaped interview from 1983, Lucille Armstrong calls her late husband “Louie” as well. Musicians and close friends usually called him “Pops”.

In a memoir for Robert Goffin written between 1943 and 1944, Armstrong mentioned, “All white folks call me Louie,” implying he didn’t use the name himself or that no white people called him by nicknames like Pops. Interestingly, he was listed as “Lewie” in the 1920 U.S. census. On several live recordings, he’s called “Louie” on stage, such as in the 1952 performance of “Can Anyone Explain?” from the album *In Scandinavia vol.1*. The same happens in his 1952 studio recording of “Chloe,” where the background choir sings, “Louie… Louie,” and Armstrong playfully responds, “What was that? Somebody called my name?” “Lewie” is simply the French way of pronouncing “Louis” and is common in Louisiana.

Family

While performing at the Brick House in Gretna, Louisiana, Armstrong met Daisy Parker, a local prostitute, and began an affair with her. He returned to Gretna several times to see her and eventually sought her out at home, only to learn she had a common-law husband. Not long after, Parker visited Armstrong’s home on Perdido Street, and that evening they checked into Kid Green’s hotel. The next day, March 19, 1919, they married at City Hall. They later adopted three-year-old Clarence, the son of Armstrong’s cousin Flora, who had died shortly after giving birth. Clarence had a mental disability from an early head injury, and Armstrong cared for him for the rest of his life. Armstrong’s marriage to Parker ended in 1923 when they separated.

On February 4, 1924, Armstrong married Lil Hardin, King Oliver’s pianist, who had divorced her first husband a few years earlier. She played a big role in boosting his career, but they separated in 1931 and divorced in 1938. Armstrong later married Alpha Smith, a relationship that had started back in the 1920s while he was playing at the Vendome and continued for years. Their marriage lasted four years before ending in divorce in 1942. That same year, in October, he married Lucille Wilson, a singer at New York’s Cotton Club, and they stayed together until his death in 1971.

Armstrong never had children from his marriages, but in December 2012, 57-year-old Sharon Preston-Folta claimed she was his daughter from a 1950s affair with Lucille “Sweets” Preston, a dancer at the Cotton Club. In a 1955 letter to his manager, Joe Glaser, Armstrong expressed his belief that Preston’s newborn was his child and instructed Glaser to provide a $400 monthly allowance (about $5,869 in 2024) to support both mother and daughter.

Personality

Armstrong was colorful and charismatic. His autobiography vexed some biographers and historians because Armstrong had a habit of telling tales, particularly about his early childhood when he was less scrutinized, and his embellishments lack consistency.

In addition to being an entertainer, Armstrong was a leading personality. He was beloved by an American public that usually offered little access beyond their public celebrity to even the most significant black performers, and Armstrong was able to live a private life of access and privilege afforded to few other black Americans during that era.

Armstrong generally remained politically neutral, which sometimes alienated him from other black Americans who expected him to use his prominence within white America to become more outspoken during the civil rights movement. However, Armstrong criticized President Eisenhower for not acting forcefully on civil rights.

Health problems

The trumpet can be tough on the lips, and Armstrong dealt with lip damage for much of his life. His bold playing style and choice of narrow mouthpieces, which stayed in place but pressed into the soft skin of his inner lip, were big factors. During a European tour in the 1930s, he developed such a severe ulcer that he had to stop playing for an entire year. Over time, he used salves and creams to soothe his lips and even trimmed scar tissue with a razor blade. By the 1950s, he was the official spokesman for Ansatz-Creme Lip Salve.

Backstage in 1959, trombonist Marshall Brown suggested to Armstrong that he see a doctor for his lips rather than depend on home remedies. But Armstrong didn’t follow through until his later years, when his health was already declining and surgery was deemed too risky by doctors.

In 1959, while touring in Italy, Armstrong was hospitalized with pneumonia. Doctors worried about his lungs and heart, but by late June, he made a strong recovery.

Nicknames

The nicknames “Satchmo” and “Satch” come from “Satchelmouth,” though the exact origin is unclear. One popular story says that as a boy in New Orleans, Armstrong would dance for pennies, then scoop them up and stash them in his mouth to keep them from bigger kids. Someone supposedly called him “satchel mouth” because his mouth acted like a satchel. Another version is that his large mouth simply earned him the nickname, which was later shortened to “Satchmo.”

Early on, Armstrong was also known as “Dipper”, short for “Dippermouth”, a reference to the piece Dippermouth Blues and something of a riff on his unusual embouchure.

The nickname “Pops” came from Armstrong’s own tendency to forget people’s names and simply call them “Pops” instead. The nickname was turned on Armstrong himself. It was used as the title of a 2010 biography of Armstrong by Terry Teachout.[97]

After a competition at the Savoy, he was crowned and nicknamed “King Menelik”, after the Emperor of Ethiopia, for slaying “ofay jazz demons.”

Race

Louis Armstrong embraced his roots as a Black man from a poor New Orleans neighborhood and avoided what he called “putting on airs.” Younger Black musicians often criticized him for performing for segregated audiences and not taking a stronger stance in the civil rights movement. When he did speak out, it made headlines. In 1957, during a performance in Grand Forks, North Dakota, journalism student Larry Lubenow landed a candid interview with him shortly after the Little Rock school desegregation crisis. Armstrong blasted Arkansas Governor Orval Faubus and President Dwight D. Eisenhower, saying the President had “no guts” and was “two-faced.” He announced he would cancel a planned Soviet Union tour for the State Department, declaring, “The way they’re treating my people in the South, the government can go to hell,” refusing to represent a government at odds with its own citizens. The FBI kept a file on him for his outspoken views on integration. His remarks drew both support and criticism—figures like Jackie Robinson and Lena Horne backed him, while a Mississippi radio station banned his music. When his road manager, Pierre Tallerie, tried to soften his words to the press, Armstrong publicly rebuked him, nearly fired him, and insisted on speaking for himself from then on.

Religion

When asked about his religion, Armstrong said he was raised Baptist, always wore a Star of David, and was friends with the pope. He wore the Star of David to honor the Karnoffsky family, who took him in as a child and lent him money to buy his first cornet. Later, Armstrong was baptized Catholic at the Sacred Heart of Jesus Church in New Orleans and met both Pope Pius XII and Pope Paul VI.

Personal habits

Armstrong cared a lot about his health and used laxatives to keep his weight in check, a habit he recommended to friends and shared in his diet plan, Lose Weight the Satchmo Way. Early on, he favored Pluto Water, but after discovering the herbal remedy Swiss Kriss, he became a devoted fan, praising it to anyone who’d listen and handing out packets to everyone he met—even members of the British royal family.

Armstrong was known for sending humorous, slightly risqué cards to friends, featuring a photo of him sitting on a toilet as seen through a keyhole, with the slogan, “Satch says, ‘Leave it all behind ya!’” These cards are sometimes mistakenly thought to be ads for Swiss Kriss. In a live performance of “Baby, It’s Cold Outside” with Velma Middleton, he playfully changed the lyric from “Put another record on while I pour” to “Take some Swiss Kriss while I pour.” His use of laxatives dated back to childhood, when his mother would gather dandelions and peppergrass along the railroad tracks to give her children for their health.

Armstrong was a heavy marijuana smoker for much of his life and spent nine days in jail in 1930 after being arrested outside a club for drug possession. Armstrong described marijuana as “a thousand times better than whiskey.”

Armstrong cared about his health and weight, but his love for food shone through in songs like “Cheesecake,” “Cornet Chop Suey,” and “Struttin’ with Some Barbecue”—though that last one was actually about a charming companion, not a meal. He stayed deeply connected to the cuisine of New Orleans throughout his life, often signing his letters with the phrase, “Red beans and ricely yours…”.

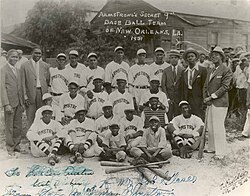

A Major League Baseball fan, Armstrong started a team in New Orleans called the Raggedy Nine, later transforming it into his own “Secret Nine Baseball” team.

Death

Ignoring his doctor’s advice, Armstrong performed a two-week stint in March 1971 at the Waldorf-Astoria’s Empire Room. By the end, he was hospitalized after suffering a heart attack. Released in May, he quickly got back to practicing his trumpet, still eager to return to touring. Sadly, on July 6, 1971, Armstrong died in his sleep from another heart attack while living in Corona, Queens, New York City.

Armstrong was laid to rest in Flushing Cemetery, located in Queens, New York City. His honorary pallbearers featured an impressive list of stars, including Bing Crosby, Ella Fitzgerald, Duke Ellington, Dizzy Gillespie, Pearl Bailey, Count Basie, Harry James, Frank Sinatra, Ed Sullivan, Earl Wilson, Benny Goodman, Alan King, Johnny Carson, and David Frost. During the service, Peggy Lee performed “The Lord’s Prayer,” Al Hibbler sang “Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen,” and longtime friend Fred Robbins delivered the eulogy.

Comments on: "The Life and Legacy of Louis Armstrong" (2)

[…] Life and Legacy of Louis Armstrong Ray Charles: Life and Influence in American Music Fats Domino’s Life: From New Orleans […]

[…] The Life and Legacy of Louis Armstrong […]